Faith in the North-East Inner-City

Introduction

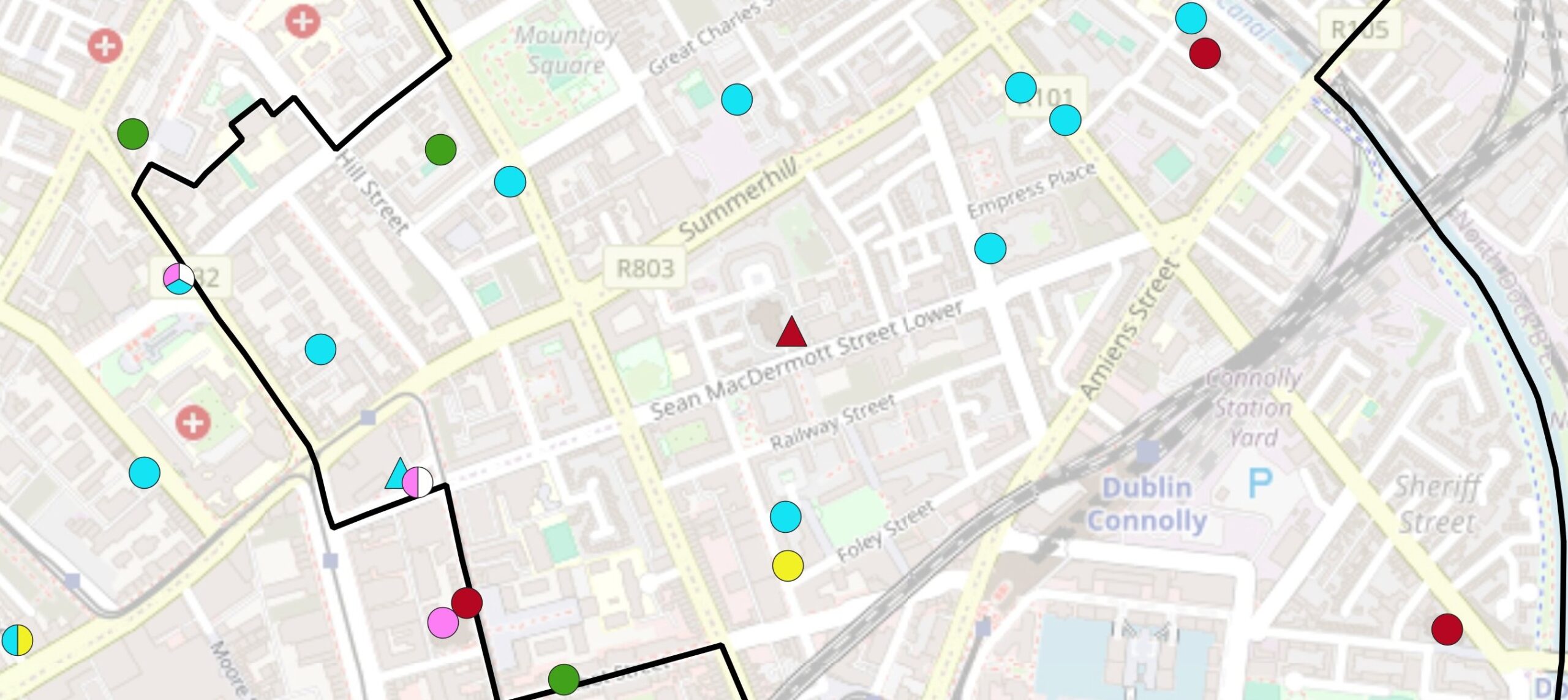

New research by the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice and ACET Ireland has identified almost fifty faith-based communities in the north-east inner-city of Dublin. A key aim of the research was to analyse the role of faith-based communities in fostering the integration of migrants, refugees, and immigrants in the north-east inner-city, and how they bridge cultural, linguistic, and social gaps, facilitating smoother transitions into Irish society while enriching the local community.

[Click image to download full report]

Executive Summary is available for download here

Supporting Integration

After conducting 30 interviews, researchers found clear evidence that faith-based communities are part of the north-east inner-city’s social infrastructure. Faith-based communities support integration in twelve primary ways and they are trusted first ports of call, locally rooted, and active across generational, class, and ethnic divides.

Recommendations

Informed by the lived experience of residents of Dublin’s north-east inner-city, six steps were developed to serve as practical steps the city council can make now. They recognise faith-based communities as part of the north-east inner-city’s social infrastructure, not as marginal institutions to be kept at a distance.

Comments from Research Team

Sophie Manaeva, TCD theology graduate and research assistant, observes that “we have identified almost fifty such communities, but this is not a stable number. Finding space and time is an issue consistently brought up by interviewees: precarious rent arrangements, health and safety hazards, heritage buildings being unfit for purpose, and limited time slots all hinder the activities of faith-based communities.” Richard Carson, CEO of ACET Ireland and researcher, noted that “In the late 20th century churches of different backgrounds sharing space was novel and noteworthy. This research shows that, in the north-east inner-city such sharing is normal” Of particular interest is how “the faith-based communities of the north-east inner city use spaces that are both familiar and hidden. Well known buildings may host multiple congregations, some communities gather in buildings down old stable lanes behind the Georgian facades.”

Carson continues “The challenge for everyone in the city is not to reinforce the burden on these communities to integrate. Rather it is to share in two-way integration, allowing ourselves to become guests to their hosting as they are already a part of our city rather than an addendum or marginal feature of it.” Kevin Hargaden, Social Theologian at the JCFJ sees this an essential insight from the research. “We have clearly evidenced a blind spot in the way that that State and her institutions are engaging with these questions. If we want a truly pluralistic and inclusive religion, our understanding of secularism has to be more sophisticated than keeping all questions of faith at a distance.” Expanding on this point, Manaeva adds that “Behind our report are dozens of stories attesting to the fact that faith-based communities are integral to the well-being of Dublin. They are the first port of call when people don’t know where to turn for help. They offer services and supports, unique local knowledge, the ability to signpost State services, as well as invaluable friendship and spiritual nourishment.”

With a note of warning, Manaeva advises that “Without them absorbing pressure that would otherwise fall on the State, integration would be happening much slower and much less effectively. Recognising this is the first step towards honouring our commitments to two-way integration and a flourishing life for everybody who calls Dublin home.” So often, recalls Hargaden, interview subjects articulated their faith as being central to their identity. “We need to go beyond 20th century ideas about religiosity if we want to see the full flourishing of contemporary Ireland.” Concluding, Carson reaffirms a key finding that “The idea that faith-based communities can be reduced to a collective form of private devotional activity has been firmly debunked by this research. They are already an active part of health and civic inclusion, their presence has profound public implications which require a response and their willingness to join others in making Dublin and the north-east inner-city a better place to be should be embraced with open arms.”

Conclusion

While the challenges faced by the north-east inner-city are unique, there is a sense in which the patterns at play here can be found all over Ireland. Resilience amid hardship, solidarity amid change, and a fundamental openness to new opportunities is common across our nation’s cities, towns, and villages. Each faith-based community embodies that story in miniature. They remind us that social cohesion is not engineered from above but nurtured in rooms where people sing, share food, and pray together.

To walk across the north-east inner-city without passing a faith-based community is difficult. To plan for its renewal without engaging them is impossible. If Dublin is to remain a city of welcomes, it must see its faith communities not as holdovers, or as guests, but as neighbours. They are co-builders of the common good, bearers of hope, and indispensable partners in shaping a city worthy of all who call it home.

Media Coverage of Research

“Look to the many faith-based groups to boost integration in inner-city, a new report advises council” Eoin Glackin (Dublin Inquirer) – 23rd October

“On Hardwicke Lane, a tiny masjid faces hostility and xenophobia, but it can’t afford to move” Shamim Malekmian (Dublin Inquirer) – 29th October

“Policymakers failing to tap into religious groups for migrant integration, says report” Sorcha Pollak (Irish Times) – 5th November

“Ignoring migrants’ religious communities fails Ireland’s integration efforts” Sophie Manaeva (Op-ed in Irish Examiner) – 6th November

“Faith Communities Co–builders of the Common Good” United Dioceses of Dublin and Glendalough – 6th November