Martina Madden

Martina Madden is Communications and Social Policy Advocate at the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice

While this issue of Working Notes considers issues of global migration from a theoretical or practical perspective, in this essay we turn to the real, lived experience of arriving in Ireland seeking refuge.

Emigrating is often a forced decision caused by poverty, unemployment or oppression. Irish people know this all too well having left these shores in our droves to escape hardships including famine and economic recessions. It means leaving behind your culture, possibly your language, and certainly several people that you love. These days, Irish people emigrate for better financial or creative opportunities, for example to Berlin, London or Dubai. The pain of leaving is tempered by the option to return home permanently some day and the ability to visit regularly until that day arrives. We may think that the era of forced migration – no choice but to leave and no option to return – is a relic of a dark past. While true for “us”, many others still live this reality.

NOT ALL IMMIGRANTS ARE EQUAL

People who immigrate to Ireland from other member countries of the EU, or from the UK, may suffer from some degree of culture shock and take a while to settle into the rhythms of life here. But even within the cohort of people who can live in Ireland without a visa, there are differences. We can assume that a highly-skilled, highly-paid tech worker who moves to Dublin to work at Google, Facebook or LinkedIn is going to have an easier time integrating than a less educated person from Romania whose cultural capital and language skills only allow them to look for work as a manual labourer. At the bottom of this hierarchy of immigrants are the men, women, and children who are forced to flee their native countries and who seek asylum in Ireland. They are the among the most poorly-treated people in our society.

DIRECT PROVISION & CORK MIGRANT CENTRE

The stress of living in Direct Provision cannot be overstated. The stress of finding yourself in an unfamiliar country, in an overcrowded centre filled with strangers and with only one room for your whole family to eat and sleep in is unimaginable for most of us. The usual means of settling in to a new place are not available to the people living in Direct Provision, as opportunities to meet and get to know local people are limited, and in addition to this there is the stigma attached to being an asylum seeker.

Despite all of this, there are reasons for hope. A recent visit to Cork to meet with groups of people living in Direct Provision who are participating in some creative and healing programmes run by Cork Migrant Centre was an uplifting experience where I was left with a sense of admiration for everyone involved, both for their upbeat, positive attitudes and their perseverance despite huge obstacles.

NAOMI MASHETI

Dr Naomi Masheti, Programme Coordinator of Cork Migrant Centre[1] is a psychologist and psychosocial practitioner, who holds a PhD in the Psychosocial Wellbeing of Sub-Saharan African Migrant Children. Naomi is a migrant herself from Kenya, and has been living in Ireland for 20 years; “a lifetime” as she says. This, in addition to her impressive credentials makes her incredibly well-attuned to the needs of people living in Direct Provision.

COFFEE MORNING FOR MOTHERS OF YOUNG CHILDREN

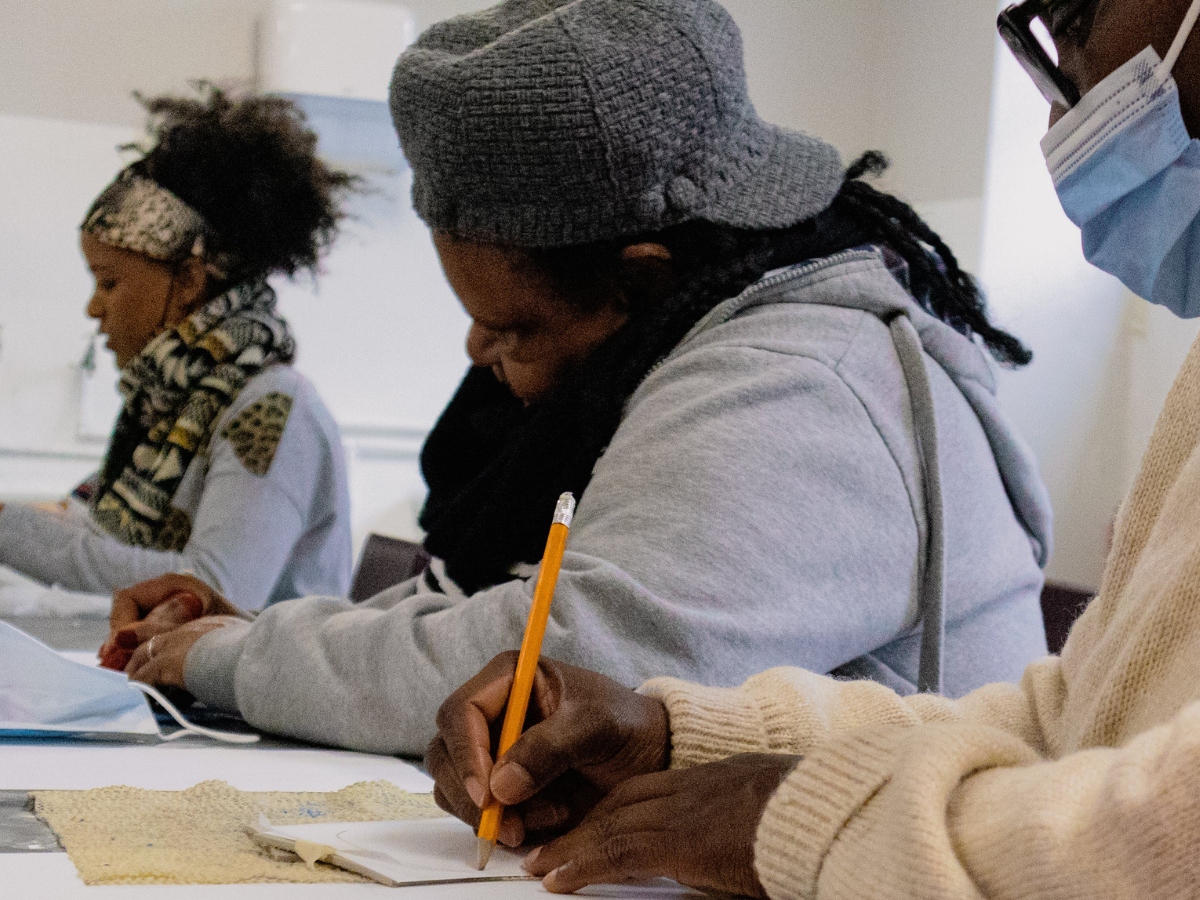

Groups of Direct Provision residents have been meeting at Nano Nagle Place in Cork city centre for more than four years. It is a safe space for people living in Direct Provision centres – to meet others, find support and learn new skills. The aim of the facilitators, led by Naomi, is to provide a setting where residents can meet people living in other centres as well as people from the local community, to increase their support network in Ireland.

I visit the centre one morning at Naomi’s invitation, to talk to her and to the women taking part in the group. The women have a warm rapport with each other and with Naomi. They greet each other with hugs and smiles and it’s clear that the connection between them all is strong. One thing that strikes me about the group is their good humour and optimism, despite all of the challenges they face. Naomi explains that transport is the greatest challenge for Direct Provision residents accessing programmes, as the projects involve bringing people from different centres together, and it is proven to be the case on the day I visit – a bus that is meant to collect residents from a centre in Macroom doesn’t show up, leaving several women unable to make the coffee morning.

Of all the people living in Direct Provision centres, Naomi says that it is hardest for mothers with young babies. They are most vulnerable to isolation and stress because it is more difficult to find ways to connect with people when the demands of minding a small baby make it difficult to get out to even meet someone for a coffee.

This was the need that the weekly coffee morning in Nano Nagle Place was responding to – to offer somewhere where mothers could take a break from their babies for an hour or so by handing them over to the volunteers who engage the babies/toddlers in developmentally appropriate activities, giving them time to relax and talk to other mothers about their week.

LINO PRINTING ART CLASS

With their small children safely engaged, the young mothers and other women in the group take an art class where they are taught how to make lino prints. The camaraderie among the group is strong and they chat and laugh throughout the hour or so the class lasts.

A couple of the young children are too shy to join the babies/toddlers activities and Naomi takes a walk in the walled garden of Nano Nagle Place with one mother, “to give her a break.” After the impersonal nature of living in a Direct Provision centre, the personal care that people receive from the Cork Migrant Centre must be welcome, and healing.

HOUSING CRISIS DELAYS PEOPLE IN MOVING OUT OF DIRECT PROVISION

Several of the women I speak to tell me they were in Direct Provision for more than five years. They have had children in that time, children who still do not know anything other than sharing just one room with their family in an overcrowded centre full of people. When you have lived in an institution for a long period of time, the constraints can start to feel like safety. One woman tells me that she has had her papers for a couple of months and is preparing for the move out of the centre, but her relief at leaving is tinged with trepidation. At least in the centre, she says, there are always others to turn to, but “nobody looks out for you outside.”

When – if – the day finally arrives that the person has their asylum request granted by the State, what the women refer to as ‘getting their papers’ – there are immediately a whole new set of obstacles to surmount. First, the paperwork to get HAP[2], and then the (well documented by JCFJ) struggle to find a home that is affordable and adequate for your needs. In this, each individual and family from Direct Provision finds themselves competing with all of the other people who are looking for housing in a market where there is limited supply and extortionate rental costs. In addition to the lack of finances they also face discrimination for coming out of a Direct Provision centre. They tell me that landlords say “I’ll get back to you… but they never do.” They also report that they’re asked intrusive questions about how they’ll afford to pay rent, having just come out of Direct Provision.

Hard as it is for families to find a home, they say it’s even more difficult for single people. One of the women in the group is looking for accommodation on her own, which means finding a room in a house-share, which is proving almost impossible at the moment. Of course these issues are not unique to people coming out of Direct Provision, they are endemic in Ireland and more severe for people on low incomes or in receipt of unemployment assistance. But while discrimination is something that is hard to prove, and therefore quantify, it is plausible that when choosing a flatmate to rent the spare room, people might default to opting for someone who is feels less ‘other’ to them than a woman from another continent who currently lives in a Direct Provision centre. This is an additional hurdle these people have to face.

SUPPORTS IN HOUSING, EDUCATION, PARENTING SKILLS, & MENTAL HEALTH

The team at the Cork Migrant Centre are led by what the women tell them they want. At the coffee morning, some women expressed that they were feeling stressed and so the mental health workshop was born. The women come from many different countries in Africa, Eastern Europe and others. This diversity of backgrounds means that they sometimes have difficulty interpreting the cultural norms for parenting in Ireland. The team has responded to this frustration by setting up parenting courses, which help these women – who already know how to be mothers – what it is to be a mother in this particular cultural context. Naomi’s background as a psychologist is particularly helpful here. She is concerned with the psychosocial aspect of living in Direct Provision and the stress that moving to a new social and cultural world has on the individual. Direct Provision is hugely stressful for a person and a great cause of anxiety, which is hardly a surprise given the conditions that people live in. What Naomi and her team try to do is prevent or reduce that stress to mitigate the harm it does.

The help they offer is often very pragmatic. If children are not doing well in school, they can access grinds or go to a homework club. The centre has links with UCC+ and other access programmes, and can also give second-level students information about scholarship opportunities. If residents are in need of housing, they can write them a reference to show a potential landlord. She describes a lot of what they do as “signposting” [pointing people towards the information they need] and facilitating and stresses the importance of “meeting people where they are.” The centre works in partnership with several organisations including UCC, Tusla and the HSE.

SAOIRSE – ETHNIC HANDS ON DECK

The centre runs many creative workshops including one in collaboration with Cork Printmakers – Healing Through Crafts. Before Covid the women would meet up and take part in the craft sessions, learning sewing skills among other things. Then once the pandemic restrictions began, the sessions stopped. To fill the gap left by their absence the women who attended the classes decided to use their skills to make facemasks. The team at the centre raised money for the initiative with a GoFundMe appeal and funding from UCC. In four weeks the women had made 9,000 cotton masks – so many that they could donate three to each child living in a Direct Provision centre and give the excess to 14 community groups.

The impact of the mask-making was not just visible in the effect they had on slowing the spread of Covid-19 but was also visible in the sewing group itself. The women were buoyant after the initiative’s success and had increased self-esteem and a sense of agency from being able to contribute to the local community instead of feeling like they were always receiving. “The genie was out of the bottle” says Naomi, who began to seek out ways in which the group could use their experience to make some income from their work. The team formed and registered a social enterprise, Saoirse – Ethnic Hands on Deck, so that the women could sell their wares. Since then, they have produced not just masks but brooches, Christmas cards, and hair ties.[3]

THE MOTHER TONGUES PROJECT

The Mother Tongues project has also emerged from the new initiative. It was an idea that fomented at the mother and babies’ coffee mornings when the women would chat and laugh about the sayings and wisdom that their mothers had passed on to them. Despite their diverse backgrounds, they discovered that mothers around the world from Lagos to Longford often say exactly the same things! The project was born when someone had the idea to get these words of wisdom printed on tote bags. The bags are now being sold in Nano Nagle Place and in Cork Flower Shop in Glandore and will be on sale at the Mother Tongues Festival at the end of February.[4]

A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO WORKING WITH CHILDREN AND ADULTS

Fionnuala O’Connell is the Youth Coordinator at the centre. She was a volunteer in youth programmes before taking up this post and has lived in Cork since 2016. Fionnuala was born in South Africa, to a Liberian mum and an Irish dad and has lived in Ireland since 2010, so she is able to relate to the feeling of arriving in Ireland as a newcomer.

When Naomi holds the mother and baby coffee mornings, Fionnuala takes the older children and teenagers for workshops in different subjects including creative writing, hip-hop and dance. Fionnuala also facilitates a young print-making class for teenagers. The centre has collaborations with the Crawford Gallery in Cork and during lockdown ran Zoom art classes for young people.

She takes a holistic approach to wellbeing for the young people she works with and explains that a lot of the children and young adults speak different languages, so the creative workshops allow them to share a universal language through artistic outputs. In creativity, they find the medium to express themselves in a way that everyone can understand.

The workshops are run by poets, painters, singers and dance teachers who can guide the young people in a structured way, including a dance teacher from Cape Verde, and a rapper and spoken word artist. Fionnuala tells me that the young girls in particular love the dance classes and she can see how it empowers them by giving them confidence and building their self-esteem.

A lot of the children and teens in the groups Fionnuala facilitates have been born in Ireland to non-Irish parents. This, coupled with knowing only the unstable and uncertain environment of Direct Provision, makes their search for a sense of identity difficult. Direct Provision affects the confidence of children badly. They don’t get invited to sleepovers in other children’s homes. Children from some of the Direct Provision centres are given the same packed lunch for school every day, which adds to the stigma they feel and makes them a target to be picked on. They “can’t help but compare their freedoms”, she says. The workshops create a safe space where these things can be discussed.

Fionnuala explains that this exploration of feelings among older children and teens helps the work that Naomi does with parents – saying “it’s holistic, so you can’t just do one part and shut yourself off from another part.” This approach is more sustainable and it’s better for assessing the impact of the workshops and youth programmes because parents will report back on how their child is doing.

INTERNATIONAL GARDEN PROJECT, BALLINTEMPLE

The International Garden Project (IGP) is an innovative and inclusive new programme which is run by the centre. It’s based on a plot of land in the Cork city suburb of Ballintemple, situated in a peaceful convent garden which was donated by the Our Lady of Apostles (OLA) sisters there.

The IGP is a pilot programme that currently involves five families from Direct Provision centres who come to the OLA grounds each Saturday to begin the work of preparing the ground and planting seeds for harvest. If this is a success – and early signs indicate that it will be – it will expand to include more families. The land is being prepared to plant seeds, with huge support from the students of a horticulture school on sight and Nelson Abbey of Johnson Controls, Cork so that the families can grow food from their homelands. IGP is all about growing food ‘in solidarity’ and in this respect, there is a whole range of groups that are involved, from Green Spaces for Health, Social and Health Education Project (SHEP) Cork, Cork Food Policy Council, Cork City Council, Social Inclusion, Parks & Recreation Dept., and Cork City Council; to Cork Community Gardaí. Naomi tells me that there are already several ethnic shops in Cork selling food native to the countries the families come from, so they thought it would be a good idea to do it themselves.

The garden grounds are easily accessible from Direct Provision centres in Cork, and also in Kinsale, making it an ideal location for the programme. Because of the nature of the work, it is a suitable activity for people of all ages, so mums, dads and babies can all come along to enjoy the fresh air and get involved.

The garden seems like a metaphor for the work being done by Naomi, Fionnuala and others in Cork Migrant Centre in connecting people with home, while helping them to grow and flourish in new soil.

* For reasons of privacy and security the names and identifying details of the women who attend programmes at Cork Migrant Centre have been omitted from this article.

Download a pdf of this article here

Footnotes:

[1] Cork Migrant Centre, accessed 12 April 2022, https://corkmigrantcentre.ie/

[2] Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) is a subsidy paid by local authorities to households, who are eligible for social housing, to source their own accommodation in the private rental sector.

[3] Find out more about this project on social media: Twitter @ethnichands, Instagram @saoirsehd, Facebook facebook.com/SaoirseEHD.

[4] Mother Tongues, “Mother Tongues Festival”, accessed 12 April 2022, https://mothertonguesfestival.com/