Every person has a right to purposeful activity and a living income. The people of central Dublin were deprived of these rights when they were locked out of work with little or no income for four months in 1913. In remembering this tragic event I will try to situate it in a context of labour relations. Although the past is a foreign country, the core issues of the dispute remain and are being played out at a global level. The exclusion of the people of central Dublin in 1913 is a case that might throw light on the exclusion of vast numbers of people in today’s world and suggest pathways towards sustainable relations.

‘The Social Question’

Nineteenth century industrialisation in Northern Europe produced wealth but did so in a way that left the slum-dwelling masses in misery. People such as Adolph Kolping, a priest in Cologne, saw how industrialisation and social change added to the poverty of working people. With the breakdown of the guild system, journeymen lost their place in the household of their masters. Kolping sought to redress this by founding associations and providing accommodation through a movement that lasted until the Third Reich.

Bishop Ketteler of Mainz was also concerned for the working class and developed influential views on social reform, outlined in his book, The Labour Question and Christianity, published in 1864. He proposed that the well-being of working class people was the Church’s responsibility; this view was to influence Church policy at a later date.

Around this time, Karl Marx, with a different analysis, approached the same question of the social relations that arise out of the economy. The structure of the firm, the process of production, the system of exchange, the organisation of markets and the class structure all contributed, he observed, to antagonistic social relations.

In 1891, the Church took a stance on the social question in Rerum Novarum, the encyclical letter of Pope Leo XIII on the Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor.1 In the encyclical, Pope Leo refers to:

… the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class … [who] have been surrendered, isolated and helpless, to the hardheartedness of employers and the greed of unchecked competition. (n. 3)

Leo elaborates on the rights and duties of capital and labour and prescribes that the working poor should receive a living wage that would enable them to be housed, clothed, secure, and to live without hardship; that they should not accept unjust treatment as though it were inevitable, and should stand up for their rights, protect their interests, make demands and press their claims. The principal means for doing this he sees as the formation of unions. He worries about the damaging effects of industrial conflict and says that the state is obliged to prevent strikes by removing ‘in good time’ their underlying causes, such as poor working conditions and insufficient wages. He argues that the problem can be resolved in a reasonable manner if workers unite in associations and, placing justice before profit, act for their own welfare and the welfare of the state. He believes that if the state makes use of its laws and institutions, if the rich and employers are mindful of their duties, and if workers press their claims with reason, then there might be a remedy for this vast evil (the condition of labour) before it becomes incurable.

The Labour Movement

The labour movement of the nineteenth century arose in response to emiseration of workers in industrial society. After 1850, the trades unions succeeded in organising, in gaining respect for the position of the craft worker in the Victorian labour market, and in bargaining for reasonable wages. The organisation of unskilled workers remained a problem until the 1890s when ‘new unionism’ with its low subscription rates, mass membership, and ideological solidarity carried out successful strike action followed by meaningful bargaining and wage improvement. This new unionism led to the rise of the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL), founded in 1889. It was as an organiser for this union that James Larkin came to Ireland in 1907 and had considerable success in ports from Belfast to Cork.

The political arm of the labour movement succeeded in establishing, at the turn of the century, labour parties that gained electoral influence. In return for Labour’s help in the 1905 United Kingdom parliamentary elections, the Liberal Party enacted, with Conservative acceptance, the Trade Disputes Act, 1906. This gave workers and their unions wide freedom of action, especially in striking and picketing when engaged in a trade dispute. Its provisions implied, also, that the use of sympathetic and secondary strikes was protected in law. The effect was that trades unions were finally secure as organisations that could engage in recruiting and bargaining. From that point onwards, they grew in membership, with temporary setbacks, until the 1980s. Employers in the United Kingdom were hostile to the upsurge in new unionism and waged a vigorous campaign against the 1906 Act during the industrial unrest of 1911 to 1914. The Dublin employers fitted into this pattern with differences according to the specificities of the Dublin situation.

The Dublin Lockout 1913

Dublin, a provincial capital of the United Kingdom, had its own version of the social question. The city’s centre, between the canals, had a population of over 100,000 people living in the worst slums of any UK city. It represented a pool of cheap labour that supplied the busy docks and the small number of Dublin business enterprises. Job shortages and exploitative hiring practices brought about a situation where workers competed for work which went to the cheapest bidder. Paid work was, of course, vitally important, as only minimal social assistance was available from the state.

James Larkin introduced new unionism to Dublin when he founded the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) in Dublin in early 1909. With his militant approach to industrial action, a syndicalist socialist outlook, and his use of sympathetic strike action in the context of a general wave of industrial unrest, he gained significant wage increases. Larkin’s following mushroomed and the ITGWU grew rapidly.

At the same time, a new breed of craft unionists took over leadership of the Dublin Trades Council and forged a solidarity between craft and unskilled workers. Further, an overlapping set of people, as members of the Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC), founded the Labour Party in Clonmel in 1912.

In the first half of 1913, Larkin obtained increases of between 20 and 25 per cent for different groups of workers, ranging from dockers in the port to agricultural labourers in the county.2 William Martin Murphy, President of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce, discovered that Larkin was recruiting members in his Dublin United Tramway Company. In July 1913, he told his assembled employees that anyone who remained a member of the ITGWU would be sacked and he subsequently began dismissing hundreds of employees suspected of such membership.

Murphy, a leading nationalist businessman, described as a kindly gentleman, living in the leafy suburbs of Dartry, also owned Clery’s department store, the Imperial Hotel, and the Dublin Associated Newspapers, with control of the Irish Independent and the Irish Catholic newspapers. He was educated in Belvedere College. As a member of a conservative faction of the Irish Parliamentary Party he played a role in bringing down Parnell. He appears to have had strong connections with the clergy.

On Friday, 22 August 1913, Murphy visited Dublin Castle and obtained a promise of support from the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), the Royal Irish Constabulary and the military if he went ahead with his plan to force a showdown with Larkin and the ITGWU. By the following Monday, the union had balloted in favour of strike action and in the middle of the following morning, the tram workers stopped work and abandoned their trams. By employing strike breakers, Murphy had the trams up and running again within an hour.3

Two days later, DMP detectives raided the homes of Larkin and other trade unionists. Dozens of trade unionists were subsequently charged in the police courts with incitement, intimidation, obstruction and stoning trams. On Sunday, 31 August 1913, a mass demonstration took place in O’Connell Street at which Larkin appeared on the balcony of the Imperial Hotel. The police baton-charged the crowd and more than 400 people were injured. In subsequent rioting, two men died.

On the following Tuesday, 2 September, seven people died when two tenements in Church Street collapsed. An inquiry, set up two months later, revealed that the number of people living in substandard housing in Dublin was 118,461. Of these, 13,800 were living nine or more to a room. It subsequently emerged that there were 17 city councillors among the leading slum landlords.

On Wednesday, 3 September, at a meeting of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce, Murphy unveiled his strategy to crush the ITGWU. More than 400 employers agreed not to employ members of the union and over the following few days thousands of workers were told to sign forms resigning from the ITGWU or dissociating from it, if in another union. In the coal trade alone, 1,500 men were laid off.4 The upshot was that the employers locked out 20,000 workers for not renouncing their right to trade union organisation. Their dependants, 100,000 people of Dublin’s inner city, were reduced to the most extreme poverty over the following few months.

Failure of Conciliation Efforts

Following the industrial unrest earlier in the year, and before the lockout began, the Lord Mayor, Lorcan Sherlock, prompted by the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, William Walsh, had proposed the establishment of a ‘conciliation board’ for the city; this proposal received the agreement of the Chamber of Commerce and the Dublin Trades Council. On 21 September, James Connolly, who was deputising for Larkin, told the press that the union was ‘willing – anxious in fact’ to see the establishment of such a board, but on the following day the employers formally rejected the proposal.5

On 26 September, the Board of Trade appointed a Tribunal of Inquiry, chaired by Sir George Askwith, to investigate the causes of the dispute and try to resolve it. The Tribunal began its work on 29 September and concluded on 6 October; it recommended that workers abandon the sympathetic strike weapon, and employers their lockout, and proposed a conciliation and arbitration system be set up to resolve disputes before a strike or a lockout was declared. The unions accepted these findings ‘as a basis for negotiation’ but the employers rejected them.

In early October, following an initiative by Tom Kettle, former Irish Parliamentary Party MP, an ‘Industrial Peace Committee’ was established, and on 13 October a delegation from the Committee met the Dublin Trades Council which agreed to a ‘truce’, if the employers would agree. The Dublin Employers’ Federation responded that it was impossible to deal with the workers ‘due to the domination of the legitimate trade unions by the Irish Transport Union’.6 In protest at this, 8,000 ITGWU members marched through Dublin. The Industrial Peace Committee formally wound up its activities saying: ‘The employers feel their duty to themselves makes it impossible for them to pay any attention to the claims of Irish workers, or to public opinion in Ireland’.7

In November, Larkin, writing in the newspaper which he had founded in 1911, The Irish Worker and People’s Advocate, stated:

This great fight of ours is not simply a question of shorter hours or better wages. It is a great fight for human dignity, for liberty of action, liberty to live as human beings should live …

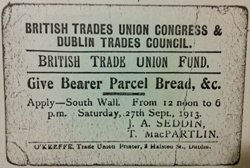

From late October, ships carrying strike breakers began to arrive in Dublin. By early November there were 600 of these ‘free workers’ working in the port; for safety, they slept on board the ships. Food ships organised by the Dublin Trades Council also arrived with food parcels donated by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in London. By the end of November, TUC funds were supporting 14,968 workers in Dublin, of whom 12,829 were ITGWU members.8

In early December, the British TUC opened negotiations with the Dublin employers. The employers would make no commitment to the reinstatement of workers but insisted that this should be entrusted to their generosity, forbearance, fair-mindedness and goodwill. Tom Mac Partlin, the chairman of the workers’ representation group, could see only the ill-will, malice, and prejudices of the employers ‘who set out four months ago to starve us into submission’ and declared that the fight would go on. The negotiator John Goode believed that the intention of Murphy to victimise some of the locked-out men ‘is a fair indication of the vindictive spirit of the employers’.9

The Dublin strike committee asked the TUC to support them with sympathetic action by their members in the transport industry in Britain. When put to ballot, this proposal was roundly defeated. This left Dublin very isolated.

From 29 December 1913, individual employments began to drift back to work under varying conditions. By late January 1914, the only help available for the queues of people outside Liberty Hall was some food parcels and one-way boat tickets to Glasgow. The United Building Labourers’ Union returned to work, agreeing to sign pledges renouncing the ITGWU. By early February, the confrontation was over.

Resisting Freedom of Association

The 1913 dispute was about the right of general workers to belong to a trade union. It was about freedom of association. It was also about the intolerable living conditions in centre-city Dublin. Murphy’s intransigent stance was informed by his dislike of ‘Larkinism’. He accepted ‘respectable’ unions but questioned the wisdom of allowing unskilled and semi-skilled workers the right to join unions because he believed that they lacked the intelligence and education not to be led astray by those, such as Larkin, whom he considered demagogues.10

Archbishop Walsh attempted to create structures of conciliation and mediation. Murphy blocked them because he believed Larkinism was a threat to business and to his vision of Irish nationality.11 He was determined to break the ITGWU. Viewed in retrospect, this was like trying to hold back the tide of the historical destiny of labour. He showed some social awareness in recognising the threat to his interests inherent in the rise of the labour movement in Ireland. But his action against the rights of a whole population is not justifiable by any measure.

In the light of the social teaching in Rerum Novarum, how was it that the local Church was not more forthcoming in its support of the workers of 1913? With the exception of the Archbishop, the Capuchins in Church Street and a Jesuit priest, Fr. Kane, none of the local clergy and few of the church-going middle class showed any understanding of official Church policy in this field. Could it be that the priests still dined out on their excellent performance during the ‘land question’ of the 1880s onwards? Was it that they came from a culture where the ethics of land ownership, private property and sexuality were individualised and absolutised, without any awareness of social ethics?

Yet there are claims that William Martin Murphy had a social conscience.12 He was a Victorian gentleman, a business man oriented to the exploitation of the factors of production, at best a paternalist employer, an anti-Parnell and Redmondite Nationalist. He had also at one time been a member of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. Laissez-faire society depends on ‘charitable works’ to provide residual care at least to the ‘deserving poor’ who fall on hard times, and sometimes even to the ‘undeserving poor’. Such forms of care arise out of an impulse of charity. But they display a lack of understanding of the structures that generate poverty and inequality in the first place, and show no willingness to tackle such inequality or advocate against it. Murphy had the social awareness to know that if the poor of Dublin were permitted to have a say in their own working conditions then the employers would have to pay fair wages at a cost to profits. But his social conscience was not informed by concepts such as equal rights, respect, or the dignity of the person. His notion of the common good was attenuated to a vision of the exclusive interests of Home Rule nationalist business men. His values were individual goals and class interests.

‘The New Deal’

The employers’ lockout victory of 1913 was quickly swept away with the collapse of nineteenth century politics into World War I and the crash of laissez-faire capitalism in 1929. By 1916, membership of the ITGWU and of trade unions in general began to grow spectacularly and continued to do so until about 1980. The Trade Disputes Act, 1906 remained intact until the Thatcher government altered it in the 1980s.

The Treaty of Versailles (1919), in a section headed ‘Organisation of Labour’, declared that ‘… peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice’ and acknowledged that working conditions involving ‘injustice, hardship and privation’ existed on such a scale as to constitute a threat to peace.

The Treaty stated that improvement of working conditions was urgently required, and called for the regulation of working hours, the provision of a living wage, the establishment of protective welfare measures, and the provision of vocational and technical education. It also called for ‘recognition of the principle of freedom of association’.

New Deal capitalism ushered in recovery in the 1930s. The Irish business sector began its ascent under an import replacement strategy. Private ownership of transport, trains and tramways failed to such an extent that the state had to take them over as loss-makers to ensure the provision of a public service. The social market economies and welfare states of post-World War II recognised the rights of labour to free association and collective bargaining and brought in a long boom that lasted for thirty years. In Ireland, the Industrial Relations Act, 1946 established a conciliation and adjudication system of dispute-resolution that has been at the heart of Irish industrial relations until this day.

The intervention of the state into market relations with a view to promoting prosperity and reducing poverty shows, in this period, its role as promoter of the common good. The state alone does not create the common good but depends on employers and labour for the production of wealth and social capital. At its best, social partnership is a form of governance which can integrate the conflicting interests of the main socio-economic players into a strategy for the common good.

The ‘Old Deal’ in Postmodern Dress

In the 1970s, stagflation in national economies emerged, as did opportunity for business in the unregulated waters of international trading. The laissez-faire doctrine of economics re-surfaced but this time applied at a global level. ‘No holds barred’ international competition emerged. Corporations are now free to operate in markets that are dis-embedded from national cultures, national politics, financial constraints and labour organisation. Many corporations have larger turnovers than the total income of nation states. Pressures are put on nation states to remove ‘obstacles’ to the freedom of action of corporations.

There has been a trend towards dismantling legal protections for trade union organisation and the employee voice on wages and working conditions. In Ireland, court challenges to employment legislation have led to decisions which have weakened employee rights, as in the cases of the landmark decision of the Supreme Court in Ryanair v The Labour Court [2007] which undermined the bargaining rights of trade unions, and the Supreme Court decision in May 201313 which found that some provisions of the Industrial Relations Act, 1946 were unconstitutional (these provisions governed Registered Employment Agreements covering some poorly-paid employment sectors).14

The collapse of the neo-liberal economy in the great recession since 2008 has resulted not in a revision of neo-liberalism but a socialising of the debts of banks and speculators, the privatisation of profits, and the subjugation of the economy and social and community relationships to markets that are controlled by the superrich.

Neo-Liberalism and ‘Precarity’

The social Darwinism of the unbridled capitalism of the nineteenth century has returned in the twenty-first century in a changed situation. The social question now applies globally as people’s livelihoods are more and more affected by international markets. What persists, through all ages, and now in a transformed context, is ‘precarity’, and those who suffer from it, the ‘precariat’. It is the condition of not being able to find a living income. The precariat of Victorian Dublin faced low wages and casual work – or no employment and a lack of social welfare protection. Today, there are growing numbers of working people who are not paid a living wage. Many experience casualisation not different from that endured by the old dockworkers. I know of workers on zero-hour contracts who pay the bus fare to factory gates where they learn that they are not required for that day. Precarious work is, by definition, uncertain, unpredictable, and risky from the point of view of the worker. Labour market security, permanent contracts, decent pay, guaranteed working hours and welfare entitlements are all being whittled away.

Globalisation causes change in the organisation of work, distancing strategic decision-makers from the point of production, fragmenting the cycle of production to obtain greater efficiencies and greater profits. Survival calls for competitiveness through quality, efficiency and cost-reduction. Notions such as ‘total quality’ and ‘world-class management’ translate into demands for continuous improvement, flexibility and work intensification. The focus comes onto downsizing, atypical contracts, wage reduction, measurement and surveillance. Practices such as the right to hire and fire without accountability, reneging on pension agreements, and evasion of redundancy payments begin to show. The phenomenon of ‘the working poor’ contradicts the idea that work is the way out of poverty in large sections of the economy.

It has already been established that trade unions play a fundamental role in defending the vital interests of workers and are forms of association with a right to recognition. Pluralist co-operation is the only way to orientate relations in the world of work. As in democracy, attempts to eliminate the other are unacceptable. In a globalising economy, the essential rights of workers, social protection, and equity must also be globalised.

This new context calls on unions to develop new forms of solidarity at global level. Work itself needs protection and development. Work is not just the market-driven production of consumer goods, or just the means to obtain the credit to be a consumer.

The human person is the subject of work as a free and creative activity. Human beings have priorities, a key one being a tendency towards establishing relationships. This is the driver of globalisation and so economic, social and political systems should have as their purpose the support of human relationships, and should be re-embedded in the life of the community.

‘The Crisis of Communal Commitment’

Distinct from the real economy but overshadowing it is the system of financial markets. In the encyclical, Rerum Novarum, when Pope Leo pointed out that working people had been surrendered ‘to the hardheartedness of employers and the greed of unchecked competition’, he added: ‘The mischief has been increased by rapacious usury … still practiced by covetous and grasping men’ (n. 3).

Over 120 years later, his words are still relevant, in the context of the profound distortions in the financial system evident in the systematic dismantling of regulation, the collapse of the markets in 2008 and the response to this collapse. The ‘rapacious usury’ of dealing in financial markets swamped the real economy of work and production, and wiped out vast volumes of wealth generated by long labour in business organisations and national economies. Judgements about the movement of money in financial markets resemble the type of decision-making found in a gambling casino. The result is that small numbers of people become inordinately rich and losers pay their debts by taxing workers and welfare recipients. A striking line from the film, ‘Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps’ (2010) encapsulates ‘the social question’ in a modern context: ‘You are part of the NINJA generation. No Income. No jobs. No assets’.

The Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), issued by Pope Francis, describes the issue as ‘a crisis of communal commitment’.15 In order to identify the values to guide the way forward, Francis makes explicit the need to reject certain core features that characterise the economic and financial system of today.

The Pope’s first ‘no’, of four, is his ‘no to an economy of exclusion’. He points out:

Today everything comes under the laws of competition and the survival of the fittest, where the powerful feed upon the powerless. As a consequence, masses of people find themselves excluded and marginalized: without work, without possibilities, without any means of escape. (n. 53)

Francis goes on to speak in very strong terms of the consequences of the process whereby human beings are commodified, used and then discarded:

… those excluded are no longer society’s underside or its fringes or its disenfranchised – they are no longer even a part of it. The excluded are not the “exploited” but the outcast, the “leftovers”. (n. 53)

He rejects trickle-down theories claiming that economic growth and the free market will inevitably bring about greater justice and inclusiveness, saying that these have never been confirmed by the facts and that they reflects a naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and a naïve belief that the market works for the good of all.

‘No to the new idolatry of money’ rejects the domination of ourselves and our societies by money. Francis sees the current financial crisis as originating in ‘the denial of the primacy of the human person’ and says:

We have created new idols. The worship of the ancient golden calf (cf. Ex 32:1-35) has returned in a new and ruthless guise in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose. (n. 55)

He goes on to say that the crisis has laid bare the imbalances in the economic and financial systems and, above all, their lack of real concern for human beings, so that people are reduced to just one of their needs – the need to consume.

Francis points out that while the earnings of a minority are growing exponentially, so too is the gap which separates them from the majority:

This imbalance is the result of ideologies which defend the absolute autonomy of the marketplace and financial speculation. (n. 56)

These ideologies reject the right of states, charged with care for the common good, to intervene:

A new tyranny is thus born, invisible and often virtual, which unilaterally and relentlessly imposes its own laws and rules. (n. 56)

He adds:

The thirst for power and possessions knows no limits. In this system, which tends to devour everything which stands in the way of increased profits, whatever is fragile, like the environment, is defenseless before the interests of a deified market, which become the only rule. (n. 56)

The third ‘no’ is to a financial system ‘which rules rather than serves’. Such a system, Francis says, rejects ethics as counterproductive, as being ‘too human, because it makes money and power relative’ (n. 57). An authentic ethics would make it possible to bring about balance and a more humane social order. Economics and finance need to be re-embedded in an ethical approach which favours human beings.

The fourth ‘no’ is to inequality. Francis notes that today in many places there is a call for greater security but says: ‘… until exclusion and inequality in society and between peoples are reversed, it will be impossible to eliminate violence’ (n. 59). He argues that if the evil of injustice is embedded in society there is a constant potential for disintegration; unjust social structures ‘cannot be the basis of hope for a better future’. He states:

We are far from the so-called “end of history”, since the conditions for a sustainable and peaceful development have not yet been adequately articulated and realized. (n. 59)

Conclusion

In 1913, there was no advocate for the common good. The laissez-faire system regarded the living wage and the common good as distorting the operations of the market. The captains of the real economy wanted to source labour as cheaply as possible and asserted the value of the profit-making system above all else. The advance of trade unionism asserted the value of working people over the interests of trade and profit. With no floor of human rights, the employers in 1913 could act below this standard.

Today, the laissez-faire system is globalised, to some extent in the real economy, and almost totally in the financial system – a system in which it is not illegal to act unethically. In the circumstances of today, therefore, there is continuity in the call for trade unions to find ways of universalising solidarity and for the international agencies to find ways of moving towards the global common good.

Notes

- Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor), 15 May 1891, n. 3. (http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/leo_xiii/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_15051891_rerum-novarum_en.html)

- Pádraig Yeates, ‘Lockout Chronology 1913–14: Historical Background’ (Available: http://www.siptu.ie/media/media_17016_en.pdf)

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Desmond Ryan (ed.), James Connolly, Socialism and Nationalism: A Selection from the Writings of James Connolly, Dublin: The Sign of the Three Candles, 1948.

- Pádraig Yeates, Lockout: Dublin 1913, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

- Pádraig Yeates, ‘Lockout Chronology 1913–14: Historical Background’, op. cit.

- Thomas J. Morrissey, William Martin Murphy, Dublin: UCD Press, 2011.

- McGowan & others v The Labour Court, Ireland & another [2013] IESC 21.

- Another case which might be noted is that of Nolan Transport versus the trade union, SIPTU. In 1994, the High Court found there were technical faults in a SIPTU-organised strike in Nolan Transport and it awarded substantial damages against the union. The decision of the High Court was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1998.

- Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), Apostolic Exhortation, 24 November 2013, Chapter Two: ‘Amid the Crisis of Communal Commitment’. (http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/francesco/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium_en.html)

Brendan Mac Partlin is a Jesuit who for thirty years lectured in employment relations and social ethics in the National College of Ireland, where he was a shop steward with SIPTU and a delegate to the Dublin Trades Council. He now coordinates the Migrant Support Service on the Garvaghy Road, an initiative of the Jesuit Dialogue for Diversity project.