Judith Russenberger

Judith Russenberger, Christian Climate Action, is a retired mother of three, with degrees in Building Surveying and Biblical Studies, and a member of the Third Order of the Society of St Francis. Her activism has included weekly vigils outside the British Parliament, Lloyds of London, and the headquarters of Shell and BP. Her writing can be found at: www.greentau.org

INTRODUCTION: THE ECOLOGY OF PROTEST

Ecology is the branch of biology that studies how organisms interact with their environment and with other organisms. From the initial colonisation of a blank canvas – a rock surface or pool of water – by living organisms that multiply and provide the elements that attract more and different organisms, the ecology of the space develops.

As successive organisms, plants and creatures reside in a habitat, the vitality and diversity of that environment expands and becomes more complex. Between the different species there will be interdependent relationships; in the typical imagination, some will be predator, some prey. More

commonly, however, others will exist in more cooperative relationships. We can think of worms that

digest fallen leaves allowing key nutrients to be made available once more for the local plant life, or zebras and ostriches that graze together relying on each other’s particular skills: zebras enhanced sense of smell and hearing and the ostriches’ enhanced visual skills, giving early warning of predators. Some of these will be keystone species whose presence keeps the different competing parties in sustainable balance; think of the interrelationship between rabbits and foxes. Over time, every possible niche in the ecosystem is filled, every opportunity embraced and every advantage achieved. The net result is a highly complex, rich and diverse community of species. Ultimately, the ecosystem attains a peak status – that of a climax community – and typically the greater the biodiversity, the greater the stability.

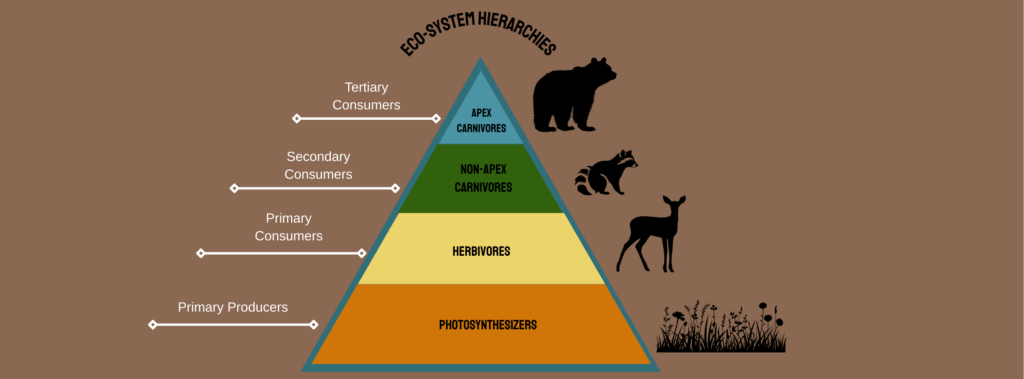

The development of an ecological system involves the creative coexistence or co- habitation of various organisms, forming a hierarchy with a few apex predators (tertiary consumers) at the top, a greater number of non-apex carnivores (secondary consumers), then an even greater number of herbivores (primary consumers) and below them photosynthesizers (primary producers). The right balance between the different groups ensures the stability of the ecosystem. Whilst apex predators are often seen as the keystone species, critical species may be found at different levels in the hierarchy. If democracy is imagined as a huge ecosystem of human interaction, we can think of protest as a critical species of speech and action – an essential element of what it means to live in a society that stably and seriously pursues justice.

A rich – in terms of wellbeing and opportunity – and stable community that is both diverse and harmonious, is what we all seek. As Christians, I think we would see such a community as one that echoes the Kingdom of God. Sadly, it is not a state of being that we currently see in the world. As a result of human greed and over-consumption, an inability to share and be generous, and an aptitude for perversely ignoring scientific evidence, we live in a world threatened by a climate crisis, a biodiversity crisis and a social justice crisis.1 As Christians – and indeed surely as human beings – we are called to seek a mutually better way of living together on this Earth.

I have, over the last five years, become increasingly involved as an activist with Christian Climate Action.2 Our campaigns seek an end to all three crises covered by Pope Francis’ formulation of “integral ecology”: climate, biodiversity, and global social justice. Our actions are varied in size and scale from solo prayer

vigils to the occupation of the offices of financial institutions. They are always peaceful.

Just as the world is not populated by one species but by an interconnected and interdependent ecosystem encompassing a diversity of species, so the world of protest is an interconnected and interdependent ecosystem. Just as diversity enables a rich and flourishing environment in the world of flora and fauna, so diversity ensures a rich and flourishing environment in the world of protest. And this environment is essential for a properly functioning democracy.

WORDS AND ACTIONS OF PEACE: WHAT PROTEST SHOULD BE

A peaceful protest has two components: it promotes or achieves a peaceful outcome, and it is carried out in a peaceful manner. Peace is more than an absence of violence; it is a place or process dependent on justice and wholeness. Peaceful outcomes are therefore those that focus on achieving justice and wholeness. So, for example, in our campaign asking Christian Aid to drop Barclays as its bank, we sought to ensure that fundraising given to Christian Aid was not indirectly financing activities that were aggravating the climate crisis and directly damaging the vulnerable communities being supported by Christian Aid.3 We wanted to achieve an outcome that was just and coherent.

To protest is to challenge, to take action – verbal or physical – in order to achieve change. What, then, is peaceful protest? What words or actions can be encompassed?

Words of peace are truthful. Lies and misdirections do not promote justice. Nor do words of slander or hate. But equally, half- truths and greenwashing are destructive. As Christians, we are called to speak truth to power even when the truth is uncomfortable to hear. What about the tone? Shouting can effectively attract attention but can also create a response of fear or anger. Discernment is needed. Singing, on the other hand, can both attract attention and be calming and engaging. Sometimes, the most effective mode is silence. Silence in our world can be unexpected and arresting, challenging and powerful.

I have, whilst engaged in silent vigils outside Parliament, been witness to several protests which

have been loud with noisy shouting, trumpeting, and horn blowing, and where the words have been

inflammatory. The overall atmosphere was intimidating and aggressive. This may be the traditional

mode of protest, but perhaps it is time to explore alternatives.

What of actions? Carrying a banner or a placard is an extension of words and the same judgments apply. What of posture? Kneeling or sitting is probably the least intimidating, although kneeling, because it is counter- cultural, can be forceful in engaging attention. Walking, as in a pilgrimage, likewise has its own positive strength. Marching can also be forceful but depending on the manner of the banners, placards, and spoken words, can be either peaceful or aggressive. Marching may also be accompanied by musical sounds. I think the noise of a samba band, although loud and therefore disruptive, is a powerful statement of presence that is both challenging and peaceful.

Actions may involve street theatre such as a “die-in” where participants lie down on the street (sometimes shrouded under sheets) to demonstrate the impact of the climate crisis. Or where a dead tree is presented to an organisation as a metaphor for the destruction their activities are causing. Or actions might include song and dance. With a particularly Christian slant, actions have also included acts of street worship: prayers and laments, washing of feet or cutting off of hair, and celebrating the Eucharist.4

WHY PROTESTING ABOUT PROTEST IS IMPORTANT

On January 29th and 30th this year, over a thousand people sat in the road outside the Royal Courts of Justice to protest at the deliberate diminution of the right to protest in the UK. Inside the Courts an appeal brought by 16 climate protesters challenging the severity of the sentences they had been given was being heard.5

As we sat back-to-back silently on the road in three orderly lines, police officers walked up and

down the lines, stopping to address individuals asking them to move.

“We recognise your right to protest, but this is a live road.”

“What can we do to make you move?” “Please move to the designated protest area, in between the

church and the courthouse.”

“A Section 14 notice may be imposed onthis section of road, and then we may arrest you.”

“You might spend hours in a police cell.”

This was a silent vigil, so most chose not to respond to the police. Instead, maintaining the silence with eyes downcast, we resolutely continued to sit in the road.

Yes, we were blocking the road. Yes, we were preventing vehicles from using that section. Why?

Because – yes! – this was a protest. And what is a protest if it does not cause some degree of disruption?

The reason for any protest is to raise awareness – to draw people’s attention – to an issue in order to effect change. This protest was about the failure of the system to allow justifiable and reasonable protest.

Over the last few years, the right to protest has been crushed and demonised by the British government through new laws, by judges through punitive interpretation of laws and sentencing guidelines, and by corporate interests through their ability to drop quiet words into significant ears, and their ability to afford the cost of legal actions and injunctions.

Where once walking peacefully along a street was considered a valid means of protest, it is now designated as a “public nuisance.” Where once sitting and blocking a road was considered a valid means of protest, it is now designated as a “disruption of national infrastructure.” Have we reached a situation where you can only protest by staying quietly on the pavement, well away from anyone or anything you might possibly disrupt?

Protest is meant to disrupt. It is meant to irritate. It is there to draw attention to a situation that needs to change. Yes, protest has to be proportionate. Yes, protest has to target the appropriate audiences. Yes, protest has to be based on valid claims. What more valid claim is there than the climate and biodiversity crisis accelerating all around us?

DEVASTATING THE ENVIRONMENT OF PROTEST

The climate crisis is the biggest existential crisis that we humans have ever faced. A delayed car journey diminishes into insignificance compared with the potential loss of life of millions of people.

The climate crisis has no favourites; it can and will continue to affect us all. There is no audience that

can argue that it doesn’t threaten them.

The climate crisis is a scientifically hypothesised, modelled and proven crisis. There is no valid data

that proves otherwise.

And yet since the rise of Extinction Rebellion in 2018, and of subsequent groups such as Insulate Britain and Just Stop Oil, governments, judges and the UK Criminal Prosecution Service have gone out of their way to silence the reasonable and peaceful protest of citizens concerned by the reality facing us.

Initially, peaceful protesters could rely on the defence of “necessity,” meaning that their violation of the law (such as obstructing the road) was necessary to prevent even greater harm from occurring. However, in February 2021, the UK Court of Appeal quashed the convictions of the Stansted 15 and ruled that activists could not rely on the defence of necessity.6

In 2022, following the action of the Colston Four (who tipped a statue of Edward Colston, a prosperous 17th-century slave-trader and benefactor to the city of Bristol, into the harbour), the Court of Appeal ruled that the defence of lawful excuse under Article 10 and 11 rights under the European Convention of Human Rights could not be presented to a jury in the future.7

In April 2023, Judge Collery, in the case of Marcus Decker and Morgan Trowland, ruled that the defence of reasonable excuse did not include the mass loss of life caused by the climate crisis.8 Some judges, including Judge Silas Reid, have banned the use of words such as “climate change” and “fuel poverty” in their courtrooms.9 When judges direct jurors to ignore the motivation of the defendants when determining their guilt or innocence, and rather to follow solely a narrow interpretation of evidence, a significant alteration to our understanding of justice has occurred. This is contrary to the principle of “jury equity” which permits a jury to find innocent someone they know to have broken the law, when their conscience so dictates.10

In March 2024, the Court of Appeal ruled that evidence of the effects of climate change would not be admissible in future cases. Such evidence had been used to support the defence of consent. This excludes, a priori, any argument that affected people and organisations would have to tolerate the disruptive action had they known about the danger they were facing (e.g. the impact of the climate crisis). It is straightforward to imagine that they could come to the conclusion that the contested actions were justifiable – necessary even – considering the significance of the warning that must be communicated.11

The Public Order Act of 2023 introduced a number of new criminal offences, including locking-on, causing disruption by tunnelling, obstructing major transport works, and interfering with key national infrastructure. The latter clause includes “A” and “B” roads such as The Strand, that runs in front of the Royal Courts of Justice. The Act aims to increase the police’s ability to restrict and criminalise protest

activity, and specifically names Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, and Insulate Britain. The Act

redefines serious disruption as hindering day-to-day activities such as a journey to work and causing delays to a more than minor degree.12

Protestors are not only being challenged by the processes of the criminal courts, but also by organisations and companies rich enough to pursue them through the civil courts. Bodies such as Shell and the National Highways Agency have taken out injunctions against both specific people and “persons unknown”, preventing them from carrying out certain activities – e.g. blocking a road, entering particular locations, or associating with certain people. Dwell for a moment with the realisation that corporate entities can now legally force British citizens to stay away from their friends. Any breach of an injunction

can incur up to two years in prison or an unlimited fine. “Persons unknown” (not specifically named in the injunction) can be charged if they breach said injunction. In some cases, a protester can be tried twice for the same offence; once in the civil courts for breach of an injunction and again in the criminal courts. Persons named in the injunction can also be charged with the legal costs incurred by the company/organisation in issuing the injunction.13

Sentencing practice has seen longer prison sentences being imposed. Previously, the so- called “Hoffman’s bargain” applied, whereby if protesters were peaceful and did not cause excessive damage or inconvenience, the State would show proportionate leniency to reflect their conscientious motives.14 However, this is no longer the norm and sentences are now being designed to be both punitive and to act as a deterrent to further “legal” protest.15

THE BOUNDARIES OF FAITH AND PROTEST

The appeal case heard at the Royal Courts of Justice on 29th and 30th January involved 16 peaceful

protestors involved in four different cases. They had received a combined prison sentence of 41 years. In response to the sentencing of Daniel Shaw to four years in prison, the UN Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention, Michel Forst, wrote “[t]oday marks a dark day for peaceful environmental protest, the protection of environmental defenders and indeed anyone concerned with the exercise of their fundamental freedoms in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.”16

At the time of writing, six of those appeals were successful, though the fact that others failed underlines that there has been no “improvement in the law for the sentencing of peaceful protestors.”17

One of the 16 prisoners, Gaie Delap, is a 78-year-old Irish Quaker who was sentenced to 20 months for her part in disrupting traffic on the M25 when protestors unfurled banners from gantries over the motorway. She was released on a home curfew licence to complete her sentence at home (like Ireland, UK prisons are suffering from intense overcrowding). However, as an appropriate electronic tag could not be found that would fit her wrist, she was arrested and imprisoned.18 Such is the response of the justice system in the United Kingdom to those who, in good conscience, protest on behalf of all those who are living under the existential threat of climate change.

Ms Delap is not a household name in our church communities. But maybe she should be?

It is understandable that Christians do not want to associate with organisations that disrupt the peace. But what if peace can only be achieved if there is some disruption? What if what is required is exactly that people of faith block a road, meaning traffic has to take an alternative route? What if they decide to raise awareness about the crises unfolding within the semi-public space of an art gallery

or the lobby of an office building?

As Christians, we might draw parallels with Jesus’s disruptive actions in the temple, or the road-blocking effect of his entry into Jerusalem riding on a donkey. We might look to the examples of the prophets who broke pots, bought up pieces of land, dug holes in walls, or buried items in the ground. If the action focuses on a just and coherent outcome – such as raising awareness of climate change – and it encourages the audience (the public, the art gallery’s leadership, a company’s board, a government department, etc.) to make appropriate changes, then such actions seem to fall within the definition of peaceful. They certainly appear to be legitimate and serious witnesses to the good news Christianity proclaims.19

But what if the action involves causing physical damage such as symbolically breaking a glass door, defacing a petrol pump, or throwing paint on a building? The objective could still be to raise awareness of climate change and to encourage a change in behaviour by the audience. And still, the level of disruption and damage to goods and property is not above what the prophets did. Maybe the circumstances – the scale of the risk being highlighted, the value of the damage versus the profits of the business – allow such

actions to be seen as peaceful. If the damage became personal – breaking a house or car window, damaging someone’s clothes – or if the action involved violence to an individual or any other sentient being, then that would go beyond what is peaceful. There is a real question of discernment here. Jesus commands his followers not to harm those who came to arrest him – and heals the ear cut off one of the assailants.

CONCLUSION: SUSTAINING THE ECOLOGY OF PROTEST

In a just society, the function of a protest is disruption. Peaceful protest can be seen as a critical part of the ecology of a democratic society, the key species that ensures that injustices are addressed, that inequalities are levelled out, the biases are highlighted, and power imbalances readjusted. Where peaceful protest is quashed or suppressed, autocracy and dictatorship follow, as we have so often seen across history and across the globe.

One form of protest that I haven’t touched on is lifestyle change. Choosing to live in line with the change you wish to see – walking the talk – is a form of protest. It is saying I am challenging the assumption that, for example, flying is an acceptable means of transport, and I am, by choosing not to fly, articulating my protest. If enough people share this same form of protest, the effect can be significant and can precipitate

change. A related form of protest is to sign petitions and write letters/ emails. In fact, the two work well together. You can both give up flying –thus reducing the commercial demand for air flights, even if only by a marginal amount – and sign petitions seeking to reduce or tax or eliminate air travel.

While such forms of protest may seem basic, I would suggest they actually represent the bottom

layer of the protest pyramid. Such protests are the primary producers of change. Without individuals wanting and being willing to change their lifestyles, there is no real basis for other forms of protest. At the other end of the spectrum, the apex equivalent are the “spicy” actions which do cause deliberate disruption. Any ecosystem can only support a limited number of apex individuals; otherwise, there will be overkill, and the system will collapse. But that limited number keeps the rest of the cohabitants on their toes, keeps them alert and healthy. Disruptive actions make people stop and think. They encourage people to ask existential questions.

Interestingly, though people do not need to approve of or like the spicy actions for them to be effective. Just Stop Oil’s actions in closing motorways and throwing paint over glassed-in pictures have not been widely approved but have led to the issue of climate change and our reliance on destructive fossil fuels being far more widely talked about. And indeed, the current UK government has pledged not to license any more new oil or gas. 20

In between these two extremes of the ecological pyramid coexist the majority of peaceful protests – the vigils, the marches, street theatre, and prayer. These thrive because they are underpinned by the individual protest of lifestyle change, letter-writing, and petition-signing. They thrive because their significance is highlighted by a few disruptive actions. And they, in their turn, encourage the continued

persistence of personal protest and give impetus to the disruptive ones. Together they maintain the

thriving of a healthy democracy. Together they work to achieve the just and flourishing world that we wish to live in. Together they work to welcome in the Kingdom of God.

Footnotes

- Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ (London: Catholic Truth Society, 2015), §139. ↩︎

- CCA, ‘Christian Climate Action’, Christian Climate Action, May 2025, https://christianclimateaction.org/. ↩︎

- Hattie Williams, ‘Christian Aid to Stop Banking with Barclays after Climate Campaign’, Church

Times, 25 July 2023, https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2023/28-july/news/uk/christian-aid-to-stop-banking-with-barclays-after-climate-campaign. ↩︎ - For a remarkable account of the potency and effectiveness of worship in public space as subversive

protest, consider: William T. Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998). ↩︎ - The Canary, ‘Met Police Already Threatening Peaceful Protesters at the “Lord Walney” 16 Appeal

Hearing’, The Canary, 29 January 2025, https://www.thecanary.co/uk/news/2025/01/29/just-stop-oil-lord-walney-16- appeal/. ↩︎ - Brian Doherty, Graeme Hayes, and Steven Cammiss, ‘The Stansted 15 Appeal: A Hollow Victory for the Right to Protest?’, The Conversation, 10 February 2021, http://theconversation.com/the-stansted-15-appeal-a-hollow-victory-for-the-right-to-protest-154694. ↩︎

- Haroon Siddique and Damien Gayle, ‘Colston Four: Protesters Cannot Rely on “Human Rights” Defence, Top Judge Rules’, The Guardian, 28 September 2022, sec. Law, https://www.theguardian.com/law/2022/sep/28/colston-four-protesters-cannot-rely-on-human-rights-defence- top-judge-rules. ↩︎

- BBC News, ‘Just Stop Oil: Dartford Crossing Protesters Jailed’, BBC News, 21 April 2023,

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england- essex-65263650. ↩︎ - Anita Mureithi, ‘Insulate Britain Activists Jailed for Seven Weeks’, openDemocracy, 3 March 2023, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/ activists-jailed-for-seven-weeks-for-defying-ban-on-mentioning- climate-crisis/. ↩︎

- Defend our Juries, ‘Trudi Warner – Taking a Stand’, Defend Our Juries (blog), 22 September 2024,

https://defendourjuries.org/trudi-warner- taking-a-stand/. ↩︎ - Sandra Laville, ‘Court Ruling Erodes Climate Activists’ Ability to Defend Themselves – as the

Planet Heats Up’, The Guardian, 19 March 2024, sec. Environment,

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/mar/19/ruling-erodes-climate-activists-right-protest-england-wales. ↩︎ - I.Liberty, ‘Public Order Act: New Protest Offences & “Serious Disruption”’, I.Liberty, 11 May 2023,

https://www.libertyhumanrights.org. uk/advice_information/public-order-act-new-protest-offences/. ↩︎ - See also: Tom Wall and Josephine Casserly, ‘Civil Injunctions Restrict Protests at 1,200 Locations,

BBC Finds’, BBC News, 2 July 2024,

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cjeegzv09l3o. See also: Campaign against Climate Change, ‘Defend the Right to Protest’, Campaign against Climate Change, 20 March 2021,

https://campaigncc.gn.apc.org/ resist_police_bill. ↩︎ - J. Jones, ‘The JSO Five and the Breaking of Hoffman’s Bargain – Wildlife in Peril’, Wildlife in

Peril (blog), 19 July 2024, https://wildlifeinperil.com/the-jso-five-and-the-breaking-of-hoffmans-bargain/. ↩︎ - Róisín Finnegan, ‘The Recent Sentencing of Climate Protestors’, Six Pump Court, 9 August 2024,

https://6pumpcourt.co.uk/the-recent- sentencing-of-climate-protestors/. ↩︎ - Michel Frost, ‘Statement Regarding the Four-Year Prison Sentence Imposed on Mr. Daniel Shaw for His Involvement in Peaceful Environmental Protest in the United Kingdom’ (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 18 July 2024),

https://unece.org/ sites/default/files/2024-07/ACSR_C_2024_26_UK_SR_EnvDefenders_

public_statement_18.07.2024.pdf. ↩︎ - Friends of the Earth UK, ‘Green Groups to Intervene in Just Stop Oil Court Appeal’, Friends of the

Earth, 17 December 2024, https:// friendsoftheearth.uk/system-change/green-groups-intervene-just-stop- oil-court-appeal. ↩︎ - Anne Lucey, ‘Irish Passport Holder (77) Held in UK Prison over Christmas as Electronic Tag Too

Large for Wrist’, The Irish Times, 5 January 2025, https://www.irishtimes.com/world/uk/2025/01/05/irish-passport-holder-77-held-in-uk-prison-over-christmas-as-electronic-tag- too-large-for-wrist/. ↩︎ - How else would people who believe “That the Earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it: the world,

and all who live in it” be expected to behave? (Psalm 24:1). ↩︎ - Rob Davies, ‘Ban on New Drilling Confirmed as Ministers Consult on North Sea’s “Clean Energy

Future”’, The Guardian, 5 March 2025, sec. Business,

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/mar/05/ban-on-new-drilling-confirmed-as-ministers-consult-on-north-sea-clean- energy-future. ↩︎