Context

The Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 has come before the Dáil at a time when there has been a significant reduction in the number of new asylum claims being made in Ireland. In line with European trends, applications have dropped from a peak of 11,634 in 2002 to fewer than 4,000 in 2007.

Announcing the publication of the Bill on 29 January 2008, the then Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Brian Lenihan TD, said:

The Bill replaces all of the present legislation on immigration, some of which dates back to 1935, and puts in place an integrated statutory framework for the development and implementation of Government immigration policies into the future.1

The range and complexity of the immigration and asylum issues covered in the Bill are evident in its sheer size – the text runs to 142 pages. So far, there have been 700 amendments put forward in relation to the Bill, which is currently at Committee Stage, being considered by the Select Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights.2

Anybody reviewing the submissions that have been made on the proposed legislation or following the progress of the Bill through the Dáil, including the deliberations of the Select Committee, would be struck by the degree of polarisation, particularly on asylum and protection issues, among different stakeholders. In an opinion piece in Metro Éireann in February 2008, Conor Lenihan TD, Minister for Integration, commented:

Some of the reactions to date [to the Bill] have been somewhat knee-jerk … and in a way typical of an immigration sector that has been mobilised around the rights-based approach that sits with the determination of asylum matters, rather than bigger-picture migration.3

At the launch of the Bill, the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform emphasised the Government’s desire to tackle irregular immigration. He drew attention to the 66 per cent reduction in asylum applications since 2002 and said:

This reduction results from the implementation of strategies aimed at combating, across the spectrum, abuses of the asylum process where 90% of asylum applications are unfounded. This Bill will underpin that strategy by ensuring more efficient and streamlined processing and removals arrangements.4

The Minister said also that among the innovative features of the Bill were provisions ‘to prevent the misuse of the judicial process by a foreign national solely for the purposes of frustrating their removal from the State’.5

Concern about the Bill’s Protection Provisions

Many of the specific sections of the Bill which relate to protection,6 and indeed the overall tenor of the Bill in this area, have given rise to serious concern among a wide range of groups. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Irish Human Rights Commission, the Law Society of Ireland, and many non-governmental organisations, including the Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland, have expressed reservations about the proposed legislation.

In submissions to the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Affairs, these organisations have indicated their concern about the Bill’s provisions in relation to a range of issues, including detention, carrier sanctions, ministerial discretion, the operation of the Protection Review Tribunal and judicial review.

(An analysis of the main concerns raised in the submissions is provided in the Appendix. The analysis has been structured around six different stages in the asylum process: access to the territory; border controls; initial interview; independent appeal; judicial review; return.)

While the reservations raised about the Bill’s protection provisions have been the subject of considerable public and political debate, so far it is not evident that the Government is prepared to respond by amending the Bill. Of the 700 amendments that have been proposed, 200 have been by the Government itself. However, as The Irish Times noted on 21 April 2008, the majority of these relate to provisions affecting legal migrant workers and ‘there is less willingness to change provisions on asylum, which have been the focus of many of the Bill’s critics’.7

One of the main reasons that a higher political priority is being accorded to labour migration than to protection concerns lies in the scale of immigration relative to asylum applications. In 2002, when total net inward migration stood at 40,000, there were not far off 12,000 new applicants for asylum. The proportion of persons seeking asylum relative to labour migrants has declined significantly since then, particularly since the accession of ten new EU Member States on 1 May 2004 and the passage of legislation following the Citizenship Referendum in June 2004. By 2007, when inward migration to Ireland reached almost 70,000, there were, as already noted, just below 4,000 applications for asylum.8

Underlying Dilemmas

Underlying the framing of legislation and policy in regard to protection are certain key dilemmas which arise from competing rights. Many of the contested provisions in the 2008 Bill reflect this tension between different sets of rights. The debate about these contentious provisions is also, of course, heavily influenced by political realities.

From an Irish legislator’s perspective, a balance has to be struck between the right of the State to control its borders and the right of individuals to seek protection. In this process, account has to be taken of the fact that Ireland is subject to obligations under international law, as well as those arising from being an EU Member State.

A major factor complicating the development and implementation of asylum legislation is the phenomenon of ‘mixed flows’ – the reality that ‘among those seeking asylum [are] significant numbers of persons seeking economic betterment rather than protection’.9 It is now generally accepted that the demand for legal migration into industrialised countries far outstrips the number of opportunities provided. Where legal immigration channels become ‘plugged’, then economic migrants may seek access via the asylum channel. In its 2005 report, Migration in an Interconnected World, the Global Commission on International Migration acknowledged the challenge represented by economic migrants submitting a claim for asylum ‘in the hope of gaining the privileges associated with refugee status’.10

In the case of Ireland, a legal immigration route does not de facto exist for the vast majority of people from outside the European Economic Area (EEA); consequently, some will seek to access the territory via the asylum process – and inevitably the State will seek to implement policies to prevent this.

A second factor is the increasing sophistication of traffickers and other criminal agents involved in the movement of people across borders. Their activities pose significant challenges to states and to asylum determination systems, and significant risks for the people who in desperation avail of their services. How do asylum determination systems deal with people who arrive in the country with the assistance of traffickers but who, on the instructions of the traffickers, have destroyed their travel documents en route and relate an invented story to immigration officials? For genuine protection applicants who unquestioningly follow such instructions the consequence may be the fatal undermining of the credibility of their protection claim.

A third factor motivating states to restrict access is the difficulty of enforcing negative decisions in asylum cases. While the public may, in theory, favour removal of those whose application has been denied, there is often ambivalence in individual cases (such as those which have received high-profile coverage in the Irish media over the past few years) where people do not perceive there is an issue of public safety. On 24 July 2008, during the Committee Stage debate on the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill, Barry Andrews TD, Minister for Children, acknowledged that ‘as few as 21% of all deportation orders signed in the last four years were executed’.11

A fourth factor is the political reality that individual EU Member States (including Ireland) do not wish to appear to be more ‘asylum friendly’ – by having better standards of protection – than other Member States, for fear of receiving a disproportionate share of asylum claims within the EU.

That these various underlying motivations will have an impact on asylum policy is understandable but if the net result is that genuine asylum applicants are denied access to the territory, or to a fair hearing, then the human costs of such a policy approach are unacceptable.

Ultimately, at the heart of the issue of asylum policy is the question of credibility. From the perspective of the State, the credibility of the personal stories of individuals seeking asylum is paramount in a process which is intended to be non-adversarial. From the perspective of asylum seekers and advocates of those seeking asylum, the credibility of the asylum process is key to ensuring that each applicant receives a full and fair hearing. However, applicants often allege that, rather than the State examining the case put forward by individual applicants in an open-minded manner, there exists a ‘culture of disbelief’, so that the system is in effect biased against those seeking protection.12

JRS Ireland Protection Concerns

In this section, the main concerns of the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Ireland in relation to the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 are outlined.13

1. Immigration and Protection – Tension in Legislation

The process that led to the publication in January 2008 of the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 could be said to have started in April 2005 when the Government published a discussion document, Immigration and Residence in Ireland: Outline Policy Proposals for an Immigration and Residence Bill.

The document was explicit that its focus was on proposals for the reform and consolidation of the law governing immigration, not asylum:

In general, the Bill will not deal with the area of asylum, an area where policy is well developed and where legislation has been substantially revised in recent times in the Refugee Act 1996 and subsequent amendments.14

However, with the publication in September 2006 of the document, Scheme of the Immigration, Residency and Protection Bill 2006 (emphasis added), it became apparent that the proposed legislation would, after all, cover asylum issues. In its observations on the Scheme, the Irish Human Rights Commission (IHRC) highlighted the inherent tension that exists when asylum and other protection issues are included alongside general provisions on immigration in the one piece of legislation. IHRC believed that including protection legislation in an act that also dealt with general immigration carried ‘the potential to create legal uncertainty for the status of protection applicants’ and saw a danger that ‘access to the protection determination process may be impeded in practice’.15

Despite the reservations that were voiced following the publication of the 2006 Scheme, provisions in relation to protection were included in the Bill published in January 2008. JRS Ireland shares the concern expressed by many other organisations in their submissions on the Bill that there are inherent difficulties in including immigration and protection in the one piece of legislation. The Law Society of Ireland, for example, referred to ‘an uneasy tension in the Bill between the law on immigration and the law relating to protection’ and said that it ‘would like to see these two areas of law dealt with separately and comprehensively’.

The Law Society went on to say:

Immigration and Protection law present the State with different challenges. Immigration law will always be related to the power of the State to control the entry, residence and removal of foreign nationals. Protection, on the other hand, raises very serious human rights considerations, most particularly, the right to non-refoulement.16

A key danger of the legislative approach currently being proposed is that in certain circumstances persons seeking protection may find themselves, through no fault of their own, to be unlawfully in the State and therefore subject to arrest, detention and removal under general immigration provisions.

2. Leave to Remain

In its 1992 document, Refugees: A Challenge to Solidarity, the Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People called for asylum systems to take account of the needs of people who fall outside the strict definition of ‘refugee’ under the Geneva Convention but whose circumstances are such that they are de facto refugees. The Pontifical Council mentioned specifically those who are victims of armed conflict, natural disasters, and ‘economic conditions that threaten [people’s] lives and physical safety’.17

JRS Ireland believes that protection systems must be able to respond to the humanitarian issues that arise as a result of these various forms of enforced migration.

The reality of de facto refugees is acknowledged in the EU document, Policy Plan on Asylum: An Integrated Approach to Protection across the EU, adopted by the EU Commission on 17 June 2008. The Policy Plan notes that ‘an ever-growing percentage of applicants are granted subsidiary protection or other kinds of protection status based on national law, rather than refugee status according to the Geneva Convention. This is probably due to the fact that an increasing share of today’s conflicts and persecutions are not covered by the Convention.’18

In Ireland at present a person who has been refused a declaration as a refugee may be granted ‘subsidiary protection’, if they are deemed to be at risk of suffering serious harm should they be returned to their country of origin. Even if a person qualifies for neither refugee status nor subsidiary protection, he or she may be given ‘leave to remain’ in the State under Section 3 of the Immigration Act, 1999.

Leave to remain is granted at the discretion of the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, usually on humanitarian grounds. Under the current legislation, a person has the right to apply for leave to remain after their application for asylum has been rejected, or to withdraw from the asylum process before its conclusion and seek leave to remain. In the period 2000–2005, a total of 617 people were granted leave to remain, the vast majority of whom had been asylum seekers.19

A person given leave to remain in Ireland does not have all of the rights granted to those who have been accorded refugee status. For example, he or she is not eligible for ‘free fees’ for university education, whereas a person with refugee status who has been resident in an EU country for at least three years does qualify.20 Moreover, a person with leave to remain does not have the right to family reunification; however, anyone who is entitled to reside and remain in the State may apply to the Minister requesting that family members be permitted to join them.

The Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 proposes a ‘single procedure’ for dealing with applications from those seeking protection. The Bill specifies that the Minister should assess, in order, (1) whether someone is entitled to protection on the grounds that they are eligible for refugee status; (2) whether they are eligible for subsidiary protection; (3) whether the principle of non-refoulement under the Geneva Convention requires that they should not be returned to a country where their life may be in danger, and (4) whether there are other ‘compelling reasons’ they should be granted protection.

It remains to be clarified what will constitute ‘compelling reasons’, but it is significant and worrying that the Bill does not specifically provide that a person may apply to the Minister for permission to stay in the State on humanitarian grounds. Only in respect of procedures for revocation of residence permission or of a protection declaration does the draft legislation specify that humanitarian considerations should be taken into account.21

It seems clear that there are persons who are deserving of the protection of the State who may not meet the criteria for protection under the single procedure proposed in the Bill. It is imperative, therefore, that the proposed legislation should be amended to include specific provision, similar to that which exists in Section 3 of the Immigration Act, 1999, to enable people facing removal to seek permission to remain on humanitarian grounds.

3. Treatment of Vulnerable Asylum Seekers

In the on-going process of establishing a Common European Asylum System (CEAS) within the EU, attention has been drawn to the importance of taking account of the special needs of vulnerable groups. Article 17.1 of the EU Reception Conditions Directive of 2003 is explicit about the obligations of EU Member States to frame reception policies that are cognisant of the needs of vulnerable persons:

Member States shall take into account the specific situation of vulnerable persons such as minors, unaccompanied minors, disabled people, elderly people, pregnant women, single parents with minor children and persons who have been subjected to torture, rape or other serious forms of psychological, physical or sexual violence, in the national legislation implementing the provisions of Chapter II relating to material reception conditions and health care.22

Regrettably, Ireland has opted out of the Reception Directive so these provisions are not applicable in this country.23

In its submission to the Select Committee on the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill, JRS Ireland argued that the proposed new protection legislation should reflect the special needs of vulnerable groups where relevant, and should in particular include a provision to ensure that people in such groups would not be detained. The submission stated:

Section 58 (1) which excludes minors from detention, should be expanded to include other vulnerable categories of detainees such as pregnant and lactating women, traumatised persons, persons with special physical or mental health needs, persons older than 65 years and chronically or seriously ill persons and families with children.24

During the Committee Stage Debate on the Bill, Denis Naughten TD (Fine Gael), queried whether there were vulnerable groups other than unaccompanied minors whose specific needs should be recognised in the legislation. Barry Andrews TD, Minister for Children, acknowledged the concern but did not give any commitment that the matter would be addressed at the Report Stage of the Bill.

JRS Ireland urges that the needs of the different categories of vulnerable protection applicants identified above be specifically recognised through amendments to the current Bill, particularly in its provisions relating to detention and to procedures for assessing an asylum claim.

4. Immigration Related Detention

{multithumb}The Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill provides for four categories of immigration related detention. Three of these categories exist under current legislation: detention of persons refused permission to enter, detention of protection applicants, and detention pending removal. The additional category allows for the detention of a protection applicant while he or she is awaiting the issuing of a ‘protection application entry permit’ – a permit which allows a protection applicant enter or remain in the State for the purpose of having his or her claim investigated.

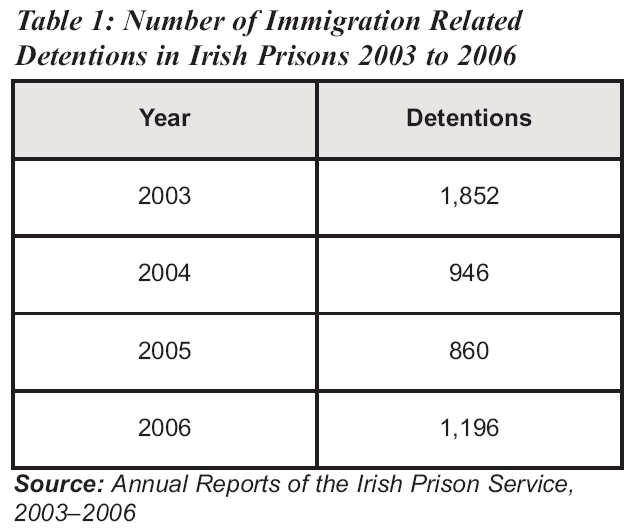

As Table 1 indicates, official figures show there was a decline in the numbers detained under immigration provisions in the years 2003–2005. However, in 2006, there was a reversal of this trend, with detentions rising by 39 per cent from the 2005 figure.

A further indication that there may be an upward trend in immigration related detention is contained in the 2007 Annual Report of the Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner (ORAC). The Report notes an increase during that year in the number of asylum claims received from people detained in prison: 385 such applications were received, and these constituted almost 10 per cent of total asylum applications in 2007.25 In 2006, applications received from people in detention represented just under 6 per cent of the total.

Among key changes to the detention provisions of the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 which JRS Ireland recommends are:

- Immigration detainees should not be detained in prisons;

- Certain vulnerable categories of protection applicants should not be detained;

- Detention of protection applicants while they are waiting for a protection application entry permit to be issued is not justified as the issuing of a permit is purely a question of administrative capacity;

- The grounds for detaining asylum applicants at the start of the process should be narrowed;

- The maximum duration of detention of protection applicants, which as currently outlined in the Bill could be potentially indefinite, should be specified as eight weeks, in line with the operational maximum that exists in practice;

- The lawfulness of any detention for the purposes of removal from the State should be assessed by a judicial authority.

Overall, JRS Ireland believes there is considerable scope for exploring alternatives to detention. Such non-custodial alternatives would allow for significant savings in financial terms, and would avoid the substantial human costs which are imposed on those detained. A welcome feature of the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 is that it allows for the release of protection applicants subject to their providing a bond or securing a surety or guarantee for the performance of the conditions of release.

5. Need for a Wider Entry Route for Legal Migrants

The Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 has been presented by the Government as if it will become the overarching piece of immigration legislation, filling gaps in legislative provision in this area. From the time it was first proposed in 2005 through to the present, new legislation in this area has been the subject of widespread public consultation and debate.

In reality, however, legislation and policy on immigration and protection have been already significantly shaped by the provisions of the Employment Permits Act 2006 – legislation that was prepared by the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment and enacted with much less fanfare than that accompanying the current Bill. A key concern of the Government in bringing forward that legislation was revealed in a comment of the then Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Micheál Martin TD, in introducing the Second Stage of the Employment Permits Bill 2005 to the Dáil. Mr Martin said: ‘we must maximise the potential for European Economic Area nationals to fill most of our skills deficits’.26

The Employment Permits Act has had profound implications for the ability of people from outside the EEA to legally enter the country: in effect, non-EEA nationals can now only access certain jobs which have a salary of €30,000+ in specific sectors of the economy where there are skill shortages. In other words, a legal route for migration into Ireland has been effectively closed to the vast majority of people outside the EEA.

The Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 will not fundamentally alter this reality. The Bill grants to migrant workers legally present in the country some additional rights and it appears that these are to be further enhanced as a result of amendments being proposed by the Government.

The motivation for moving to provide these enhanced rights was clearly a concern that skilled migrants were leaving Ireland to go to other western countries. In April 2008, Conor Lenihan TD, Minister for Integration, suggested that Ireland would have to ‘fight hard’ to retain migrants at a time of global competition for skilled workers. He added: ‘For this reason, the Immigration Bill currently going through the Dáil will need to be amended, and in a fashion that explicitly makes us more attractive to immigrants.’27

In the view of JRS Ireland, reform has to go further than this. At present, it is clear that overall asylum policy is being shaped to a significant degree by the drive to implement ever more restrictive controls on access to the territory in response to the ‘mixed flows’ of migrant workers and protection applicants already referred to.28 Such a restrictive approach is not only ultimately inefficient but is prone to creating injustices in individual cases. Offering a permanent legal route for migration into Ireland, perhaps through a quota or points system, could be part of a fairer and more durable solution.

Trends in EU Protection Policies

The Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 cannot be reviewed without considering the wider EU policy context. In general, Ireland has reflected EU trends in asylum applications and its policies have been influenced by developments at EU level.

1. Declining Asylum Claims

The statistical review, Asylum Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries 2007, issued by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), shows the first increase in five years in asylum applications received by developed countries, reversing a downward trend that had resulted in a twenty-year low being recorded in 2006. Despite the increase in 2007, the number of asylum claims received by EU Member States was still only half that in 2001.29

The overall decline in numbers in this decade is due in part to increasing stability in Europe, particularly in areas that accounted for large numbers of asylum seekers in the past – for example, the Balkans. It can be attributed also to the increasingly tough and restrictive practices of EU Member States which not only make it harder for asylum seekers to reach Europe, but make Europe as a region a less attractive asylum destination. More restrictive controls undoubtedly deny entry not only to those who are not entitled to enter, but also to many with a genuine right to protection. The closing of Europe’s borders has led to accusations of a move towards a ‘Fortress Europe’.

2. Asylum Lottery

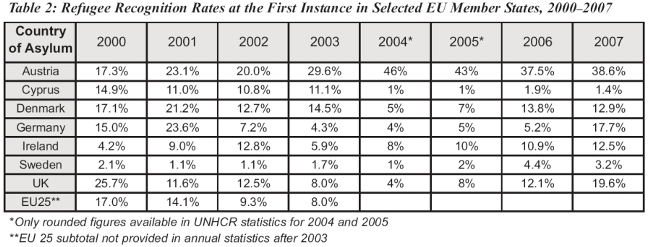

There are wide variations in refugee recognition rates between EU countries, as shown in Table 2 below. It should be noted that variations between countries exist also in the proportion of applicants accepted on appeal or granted subsidiary protection. These variations between countries in the protections offered have given rise to what some critics call ‘the lottery of asylum’ in Europe.

The EU document, Policy Plan on Asylum: An Integrated Approach to Protection across the EU, acknowledges that the differences between Members States ‘in decisions to recognise or reject asylum requests from applicants from the same countries of origin point to a critical flaw in the current CEAS [Common European Asylum System]’.30

On the other hand, the European Commission believes that ‘secondary’ movements – the phenomenon of asylum-seekers moving from one Member State to another – and multiple applications for asylum place an unfair strain on some national administrations and on asylum seekers themselves.31

3. Enhanced Cooperation

The EU Policy Plan on Asylum, in outlining the next stage of the process of creating a Common European Asylum System (CEAS), states:

As a whole, the first phase legislative instruments of the CEAS can be considered as an important achievement and form the basis on which the second phase must be built. However, shortcomings have been identified and it is clear that the agreed common minimum standards have not created the desired level playing field.32

In reality, it appears that the main focus of EU ‘enhanced cooperation’ on immigration and asylum policy has been to combat irregular migration. A host of internal policies (including carrier sanctions, visa restrictions, integrated border management initiatives), and external policies (including re-admission agreements and regional protection programmes), emphasise barriers to entry rather than protection of migrants.

In addition, more restrictive reception conditions in Member States have been introduced, making the stay of asylum seekers increasingly difficult. In Ireland’s case, asylum seekers are denied the right to work and are provided with ‘direct provision’ accommodation, food and a token social welfare benefit (the direct provision benefit of €19.10 per adult per week has not increased since its inception in 2000).

In a report in March 2007, the Rapporteur for the Committee on Migration, Refugees and Population of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe commented on asylum trends as follows:

While considering that the fight against terrorism and irregular migration are legitimate concerns for Council of Europe member states, your Rapporteur is concerned that these policies negatively impact on the effective possibility for persons in need of protection to claim and enjoy asylum in Europe.33

The Rapporteur’s comments were, of course, directed towards the situation in the forty-seven Council of Europe states as a whole, but they are also an apt summation of the current situation within the EU.

Conclusion

The ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of international migration have become ever more intertwined. It is a significant challenge for protection systems to fairly and without undue delay adjudicate on whether an applicant’s claim is based on the need for protection or is prompted by the desire for a better life. It is at times an unenviable task for those responsible for making and implementing policy to try to strike the right balance between border controls and individuals’ right to protection.

Without doubt, the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 contains provisions which if implemented would represent significant improvements in the immigration and asylum systems of this country. JRS Ireland particularly welcomes the introduction of a single procedure for determining refugee status and other forms of protection. Increased efficiency arising from the single procedure should be of considerable benefit to protection applicants.

However, JRS Ireland shares the concern of many other advocates that the Bill’s emphasis on combating unfounded asylum claims will result in denying genuine protection applicants the right to seek protection and the right to a full and fair hearing.

This article has outlined reservations about the Bill’s provisions as they relate to five key issues. Firstly, the ‘inherent tension’ between protection provisions and general immigration provisions makes the inclusion of both in the same piece of legislation highly questionable. Secondly, the current legislative proposals need to be amended to ensure that humanitarian leave to remain will continue to be an explicit component of the protection framework. Thirdly, the new legislation must give greater regard than is currently proposed to the special needs of vulnerable groups seeking protection. Fourthly, legislation and practice should provide for increased recourse to non-custodial alternatives to detention, which would allow for significant savings in terms of both human and financial costs. Finally, in dealing with the challenge of ‘mixed flows’ among protection applicants there is a role for positive immigration measures that offer people from outside the EEA a legal route to reside and work in Ireland.

Notes

- Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, ‘Launch of New Immigration Bill’, Press Release, 29 January 2008. (www.inis.gov.ie)

- Select Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Affairs, Committee Stage Amendments – Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008. (www.oireachtas.ie)

- ‘Identity Politics will only Harm, not Help’, Metro Éireann, 28 February 2008.

- Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Press Release, 29 January 2008

- Ibid.

- The terms ‘protection’ and ‘asylum’ are often used interchangeably. The Hague/UNESCO Process Handbook 2008 defines asylum as ‘the grant, by a state, of protection on its territory to (a) person(s) from another state fleeing persecution or serious danger’. Protection is defined as ‘all activities aimed at obtaining full respect for the rights of the individual in accordance with the letter and spirit of human rights, refugee and international humanitarian law’. In general, the scope of protection provisions could be interpreted as wider than asylum granted under the Geneva Convention, including humanitarian leave to remain and other complementary forms of state protection.

- Ruadhán Mac Cormaic, ‘Lenihan to Make 200 Changes to his own Immigration Bill’, The Irish Times, 21 April 2008.

- Central Statistics Office, Population and Migration Estimates, April 2007, Dublin: Central Statistics Office, 2007.

- G. Van Kessel, ‘Global Migration and Asylum’, Forced Migration Review, Issue 10, April 2001, pp. 10–13.

- Global Commission on International Migration, Migration in an Interconnected World: New Directions for Action, Geneva: Global Commission on International Migration, 2005, p. 7. (www.gcim.org/en/)

- Select Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Affairs, Committee Stage Debate on the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 (resumed 24 July 2008). (http://debates.oireachtas.ie)

- Presentation to Select Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Affairs by Deo Ladislas on behalf of the Irish Refugee Council, 2 April 2008. (http://debates.oireachtas.ie)

- A March 2008 submission from JRS Ireland dealt in detail with concerns in relation to the detention provisions of the Bill. See: Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland, Detention Provisions in the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008 (as initiated) and Suggested Amendments, Submission to the Select Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Affairs, March 2008. (http://www.oireachtas.ie/viewdoc.asp?fn=/documents/Committees30thDail/JJusticeEDWR/Reports_2008/submission47.doc)

- Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Immigration and Residence in Ireland: Outline Policy Proposals for an Immigration and Residence Bill, April 2005.

- Irish Human Rights Commission, Observations on the Scheme of the Immigration, Residency and Protection Bill 2006, Dublin: Irish Human Rights Commission, December 2006. (www.ihrc.ie)

- Law Society of Ireland, Submission on the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008, Dublin: Law Society of Ireland, 2008, p. 22. (www.lawsociety.ie)

- Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People, Refugees: A Challenge to Solidarity, 1992, n. 4. (www.vatican.va)

- Commission of the European Communities, Policy Plan on Asylum: An Integrated Approach to Protection across the EU, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions, Brussels: Commission of the European Communities, 17 June 2008, n. 1.3, p. 3.

- Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Annual Report 2007, Dublin: Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, 2008, p. 28.

- Refugee Information Service, ‘What are my Rights?’ (http://www.ris.ie/whataremyrights/refugee.asp)

- Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill 2008, Section 45: ‘Procedure for the revocation of renewable residence permission, qualified longterm residence permission or long-term residence permission’; Section 100: ‘Procedure for revocation of protection declaration’.

- Council of the European Union, ‘Council Directive 2003/9/EC of 27 January 2003 laying down minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers’, Official Journal of the European Union, L 31/18, 6.2.2003.

- Generally, when Ireland has opted out of EU immigration and asylum legislation it has been following a UK lead – this is because of the existence of the Common Travel Area between the two states. However, this is not the case with regard to the Reception Directive where Denmark is the only other country to have opted out.

- Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland, op. cit., p. 11.

- Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner, Annual Report 2007, Dublin: ORAC.

- Micheál Martin TD, Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Second Stage Speech on the Employment Permits Bill 2005, 12 October 2005, Dáil Debate, Vol. 607, No. 3. (http://debates.oireachtas.ie)

- Metro Éireann, 17 April 2008.

- The term ‘asylum–migration nexus’ is frequently used to describe this phenomenon. The term reflects the fact that migrants and refugees arrive in mixed flows and that increasingly the distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’ is hard to establish at both a theoretical and practical level.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Asylum Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries, 2007, Geneva UNHCR: 2008

- Commission of the European Communities, Policy Plan on Asylum: An Integrated Approach to Protection across the EU, op. cit., n. 3, p. 3.

- Questions and Answers on the Policy Plan on Asylum, MEMO/08/403, Brussels, 17 June 2008. (www.europa.eu/rapid)

- Commission of the European Communities, Policy Plan on Asylum: An Integrated Approach to Protection across the EU, op. cit., n. 3, p. 4.

- Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Population, State of Human Rights and Democracy in Europe, Opinion (Rapporteur: Ed Van Thijn), 30 March 2007, Dec. 11217, n. 14. (http://assembly.coe.int)

Eugene Quinn is National Director, Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland