Mariana Silva

Mariana Silva is a PhD candidate at Trinity College Dublin, working with Bord na Móna and the Environmental Protection Agency on bog rehabilitation.

INTRODUCTION: GENERATION Z, GENERATION LAUDATO SI’

I am a 26-year-old Catholic peatland ecohydrologist. My faith formation, among other Catholics of my generation,1 has been indelibly influenced by Pope Francis’ ecological writings.

My “ecological conversion”2 began when I encountered Laudato Si’ soon after my confirmation in 2015. And I fell in love with peatlands while I was an environmental engineering student at the University of Notre Dame in 2019. Wearing chest waders, hip-deep in the forested boglands in Land O’ Lakes, Wisconsin, I came to see how theological understanding and scientific curiosity are perfectly complementary, even in perhaps the least palatable of landscapes.

It wasn’t until I moved to Ireland that I discovered there were people out there willing to hike through endless stretches of bogland. Avid Irish hill walkers trek the Wicklow Way (among many Ways) in all weathers. To an extent, societal perspectives determine which landscapes are palatable and which landscapes are not.3 Yet, I believe there exists a conditionality of, a threshold for, the Irish tolerance for

bogland, which interests me terribly – more on that later.

MY RESEARCH

I study a subset of environmental engineering called ecological engineering, defined as the design of sustainable ecosystems that integrate human society with its natural environment, for the benefit of both.4

I am a PhD researcher at Trinity College Dublin supported by Bord na Móna and the Environmental Protection Agency.5 My project is designed with the structure of engineering work. I visit the remnants of the industrially harvested raised bogs, and monitor/model/make predictions about their rehabilitation. We provide an independent assessment of the “success” (varying based on one’s definition of success) of Bord na Móna’s Peatlands Climate Action Scheme (PCAS) bog rehabilitation programme.6

Although my work sits within an engineering project, it’s grounded in science – seeking a deeper

understanding of peatland ecology, soil chemistry and biology, hydrology, and more, to carry out the monitoring and modelling required. I am gathering data from regular fieldwork which describes soil water levels and carbon emissions, among other geochemical parameters. From this I can attempt to answer some purely scientific questions. Are there significant differences in current emissions between locations, and why could this be? How has the water level changed pre- to post-rehab? What vegetation communities are regrowing, and do they resemble other types of undisturbed or less disturbed ecosystems?

I will apply this scientific knowledge in the project’s engineering context to model the potential effects of Bord na Móna’s engineering interventions on the “life” of our wetlands. How will these degraded wetlands respond post- rehab? Will they ever become “bogs” again? Can we predict their future “stable state,” to design our own lives in sync?

WETLANDS 101

We may know Irish bogs through the context of their geomorphology: how they’ve taken shape over

time. We have thinner, sprawling, blanket bogs in the mountains, and deeper, domed, raised bogs in the midlands. Generally, this is true. But to get a fuller picture of the past and future of bogs, understanding the broader classification of wetlands is also important.

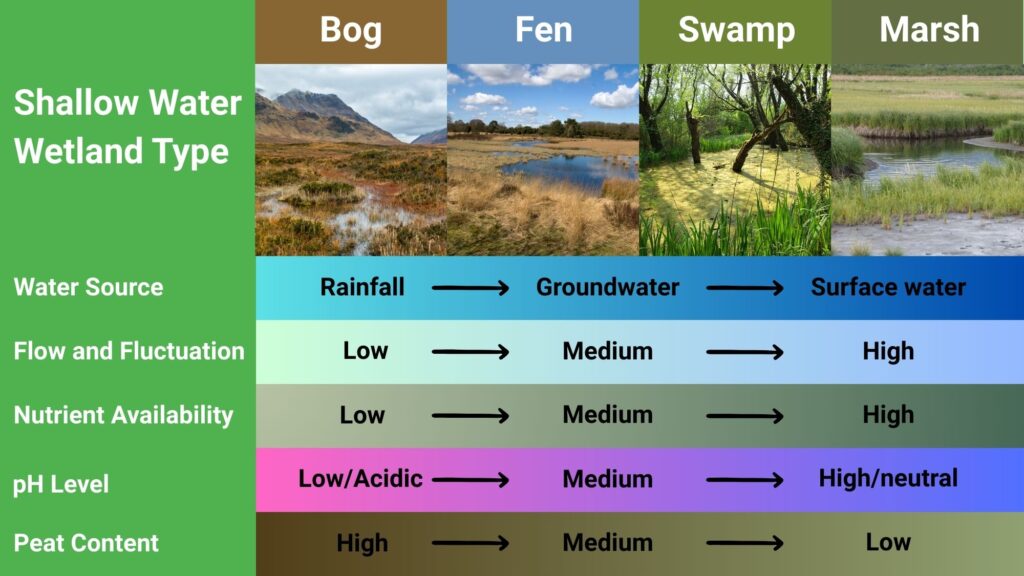

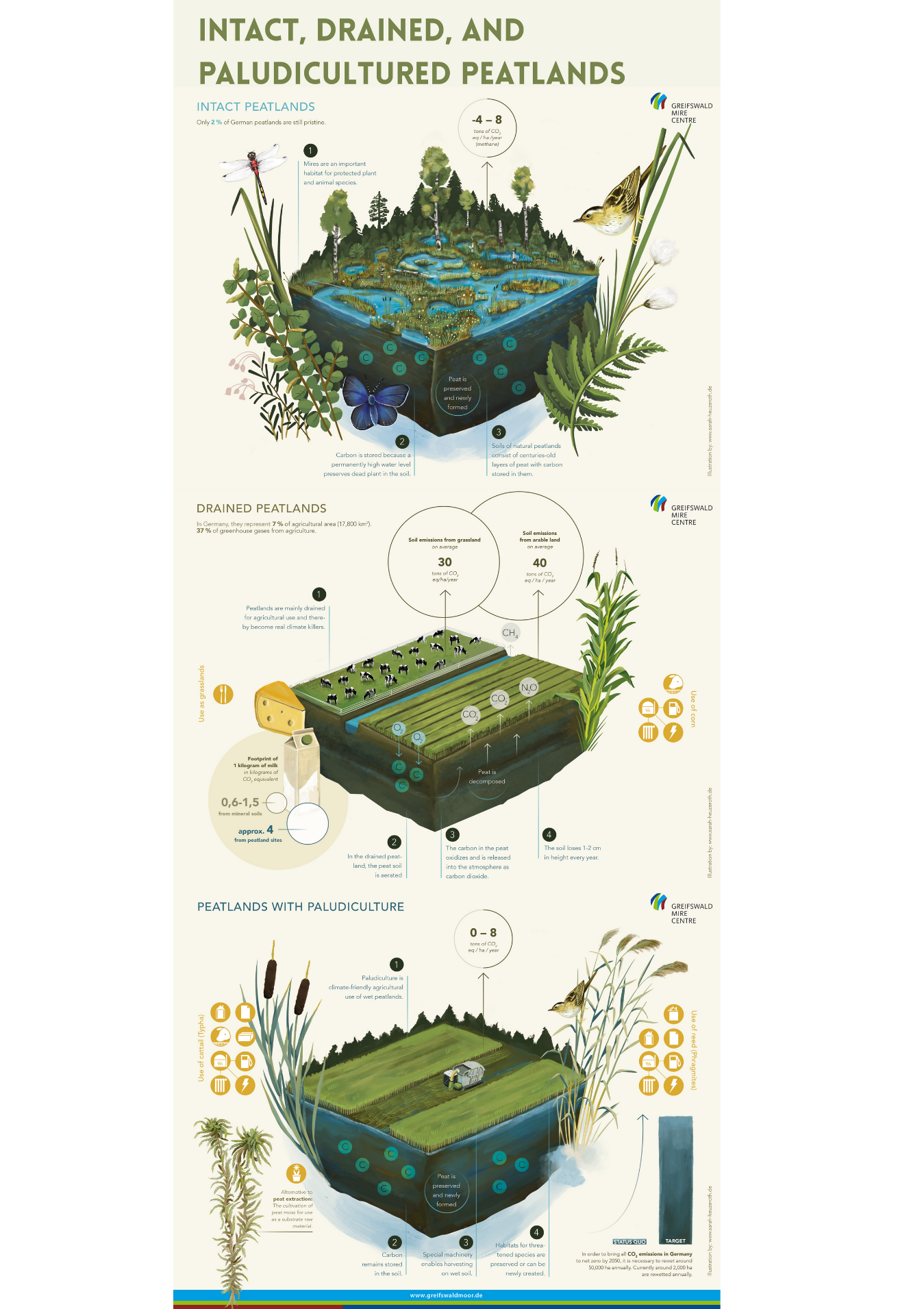

Wetlands come in two main types: peat- forming and non-peat-forming. Peat-forming wetlands include bogs and fens, where layers of dead plant material build up slowly over time to form peat soil. Bogs tend to be rain- fed and acidic, while fens draw nutrients from groundwater and support more lush vegetation. In contrast, non-peat-forming wetlands – like marshes and swamps – don’t build up peat because plant material breaks down more easily in their more mineral-rich soils. This basic difference shapes everything from how these wetlands look to how they function. In a 2022 Notre Dame Stories article I interviewed for,7 we distilled raised bog growth down to five steps over thousands of years of geologic time: from glacier-carved lakes to sediment-filled ponds, to fully “terrestrialised” peatlands where specialised vegetation takes over the surface. The slow development of deep anoxic peat is what gives bogs their famous preservation powers, of chief importance to archaeologists and historians in recent centuries.8

LIFE AND DEATH IN PEATLANDS

Human history is inextricably linked with bogs. A particularly illuminating account of this complex and evolving relationship is found in Annie Proulx’s Fen, Bog, and Swamp,9 a compelling work that significantly informs this section.

The historical human relationship with peatlands has been fraught. Much of the focus of literature and scholarship on bogs revolves around danger or death. According to the American historian John Stilgoe, bogs are a “watery wilderness” – “the spatial correlative of unreason, or madness, of the unhuman anarchy that informs so many folktales emphasizing the ephemeral stability of Christianity, society, and agriculture”. 10

Look at the left image in Figure 1: do you feel safe in it? Notice if your feelings change when you glance to the right.

Visually, bogs are perceived as vast expanses of brown, offering little depth perception to gauge distance to the nearest ridge, road, or anything. You may feel simultaneously lost and exposed. Underfoot, a wrong step may plunge you into a metre-deep pool or engulf you in soft, quicksand-like peat. In contrast, wooded groves, with solid green lawns and well-spaced trees, offer the psychological security of truly

knowing where you are in space and time.

In art and literature, this otherworldly, deadly connection is echoed time and again. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle famously sets moors as the backdrop for Sherlock Holmes’ murder investigation in The Hounds of Baskerville. In The Lord of the Rings, the Dead Marshes reflect JRR Tolkien’s memory of World War I battlefields, using the preserving power of peatlands to convey a tragic invented history.11 Examples proliferate12 but what we must also recognise is that peatlands have not always been death-bringing, historically. For earlier peoples, some of the partially-forested, transition bogland areas which we see now as bogs “would have been highly productive environments for populations accessing a variety of resources.”13

Beyond the artistic, the physical, or the spiritual, our real-life connection with death in bogs often works in the reverse direction. If we simply perceive ourselves to be unsafe in this ecosystem, a societal response would be: ‘Well, let’s try to find a way to use the land to support our subsistence.’ We seek to take advantage of it, before it takes advantage of us.

Irish audiences are likely intimately familiar with turf fires, but it is worth recalling why. Peat soil – renowned for its exceptional carbon-storing capacity – also serves as an extraordinarily efficient fuel. When cut into rectangular blocks and left to dry, peat becomes transportable and combustible,

enabling it to be used for heating and cooking, even in the most remote rural settings. This practice dates back centuries, but in the 20th century it was industrialised through the large-scale drainage of entire peatlands. The surface of these bogs was mechanically “milled” to extract peat on a massive scale – a process most notably undertaken by Bord na Móna. While this transformation inflicted considerable ecological harm, it undeniably played a significant role in the industrialisation and electrification of modern Ireland.14

The industrial age was positioned at the exact point in time rife with imperialism, class stratification, and technological advances. Esa Ruuskanen opens a captivating chapter in Technology, Environment, and Modern Britain with an 18-19th century Englishman’s firsthand account of the potential imperialistic uses for Ireland’s vast bogland.15 For England in the 18th-19th century (pre-Great Hunger), and for Ireland (by way of Bord na Móna) in the 20th century, human standards of living did improve with the more widespread use of peat for fuel.16 But we – and Bord na Móna are at the forefront here – have acknowledged that Ireland is a solidly post-industrial nation, and peat extraction should cease.17

Cultural ties to the use of this resource (especially concerning heating the home), plus a lack of trust in political regimes leave many in our communities reluctant to give up what feels like the “true” way to enact land ownership: extracting and storing turf. The embedded cultural memory of subsistence living and threat by colonialism is not to be disregarded.

Like a fear of sharks, the perceived threat of peatlands has made adversaries of humans and bogs over time, but after the Industrial Revolution, humans have been winning the battle hundreds of times over, daily. In the modern age, a bog is no longer anything to fear, but entirely something to use. Regardless, we still perceive bogs as our opposites: slicing into the earth as if we can have our cake and eat it too.

PEATLANDS, POWER, AND MORAL ECOLOGY

To translate the academic jargon into applicable lessons for Irish society, we must examine the social and ethical dimensions of our human relationship with peatlands. When in a bog, our assumptions about productivity, progress, and power are laid bare. Bogs ask uncomfortable questions of us: How do we see time? How do we assign value? And what kind of moral commitments are demanded of us in the face of ecological degradation whose full consequences will only be felt generations from now? Bear with me for just a bit more academic jargon to tease out these perspectives.

From Metabolic Rift to “Timeprint”

Peatlands continue to occupy a liminal space between life and death. Now, this boundary hinges on their response to human intervention. Our exploitation – or conversely, the effectiveness of our stewardship – could tip the scales for bogs’ survival, and for the survival of humanity in an age of climate change.

Karl Marx, writing in the 19th century, critiqued capitalist agricultural notions of “productivity” and the negative effect on soil fertility in England and Ireland. He introduced a concept now called “metabolic

rift” which applies powerfully to contemporary peatland management. Marx suggests that soil fertility “is not so natural a quality as might be thought; it is closely bound up with the social relations of the time”.18 Marx warned that industrial agriculture “simultaneously undermin[es] the original sources of all wealth—the soil and the worker”.19 His insight into delayed consequences – what we might call latency – is strikingly relevant. The hidden impact of our interventions may not manifest fully for decades, but their

imprint will be lasting. Sociologist Barbara Adam reframes this latency through the concept of a “timeprint”.20 Unlike a footprint, which requires us to witness impacts in the present, a timeprint reflects how present actions ripple through the future.

Artist Catríona Leahy’s Royal Hibernian Academy exhibition, Nature’s Own Darkroom, emulated peatlands’ fragile positioning in human timescales through her methods of printmaking.21 She described bogs as “contested landscapes”: within the social sciences this concept has significant precedent.22 But, even in their destruction, bogs demonstrate a “slow violence” not as visceral or immediate as deforestation or oil spills.23 In simpler terms, it’s much harder to “see” or know what harm we cause bog ecosystems until way after the damage is done—this is latent harm.

The Scales of Tolerance and Humility

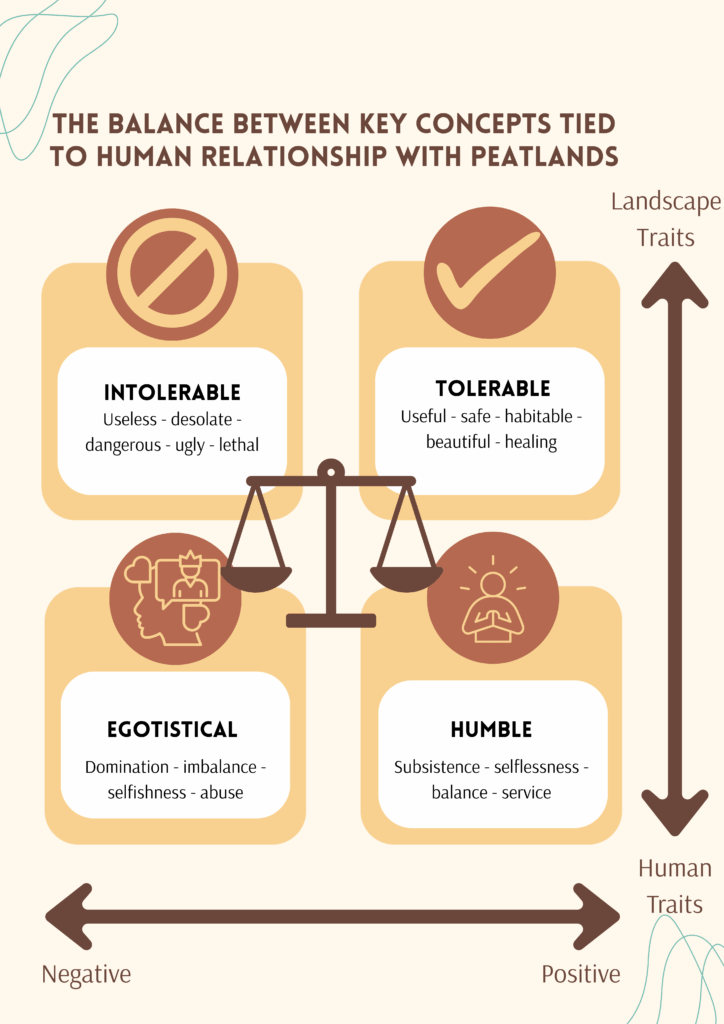

To navigate our relationship with peatlands, I propose the use of two conceptual scales: those of tolerance and humility (Figure 2). I have already described the historical conceptions of death and danger associated with bogs, which makes the tolerance scale straightforward. A highly tolerable peatland is associated with usefulness, safety, habitability, beauty, and healing. A highly intolerable peatland represents danger, wasteland, uselessness, ugliness, and even death.

Imagine a peatland which has been cutover industrially for Bord na Móna. Whether or not it is rehabilitated, it’s pretty ugly. But perhaps a still- operational cutover peatland is perceived to be tolerable

because it is useful. Or a rehabilitated one is considered safe or habitable, because the lack of heavy machinery allows for its enjoyment as an amenity. Tolerance alone, however, is insufficient. What is needed is humility – an attitude that recognises our dependence on the land, and that reframes power not as domination but as stewardship. In ecological theology, especially in Catholic thought, humans are called not to dominate but to serve Creation. The doctrine of Creatio ex Nihilo reminds us that the world is continually held in being by God – God is being, and we created things have being, and are held in existence by Him. Whatever still exists, still matters.24 As theologian Kallistos Ware puts it, “Christ as Creator-Logos is to be envisaged not as on the outside but as on the inside of everything”.25 Such a vision demands reverence, not control.

The Tension of Cultural Practice and Ecological Responsibility

This theology of humility complicates our relationship with cultural practices like domestic turf cutting. Turf cutting is often framed as a humble, arduous practice – symbolising subsistence and simplicity. Yet humility must be redefined in light of our knowledge of ecological consequences. Can a practice remain

“humble” if it imposes irreversible harm on ecosystems that are fragile, slow to recover, and critical to climate stability?

We maintain a power imbalance over the tiny things: beetles, plant roots, bird nests, things which

to a Laudato Si’-minded Catholic bear the same level of importance as ourselves. There is a personal, individual call made to all Christians to live within boundaries, aiming always to be able to do another good. This “other” includes the environment. A “humble” turf cutter can only appear humble in a purely human-centric view of our lives – humble relative only to our species as if in a vacuum.26 What passes as humble may, in fact, be a collectively egotistical mindset that involves a “dynamic of dominion” not reflective of God’s intent for humans. This trajectory is a major cause of waste and environmental abuse.27 Pope Francis says: “Once we lose our humility, and become enthralled with the possibility of limitless mastery over everything, we inevitably end up harming society and the environment.”28

CONTESTED USE: POLICIES TO PRESERVE PEATLANDS

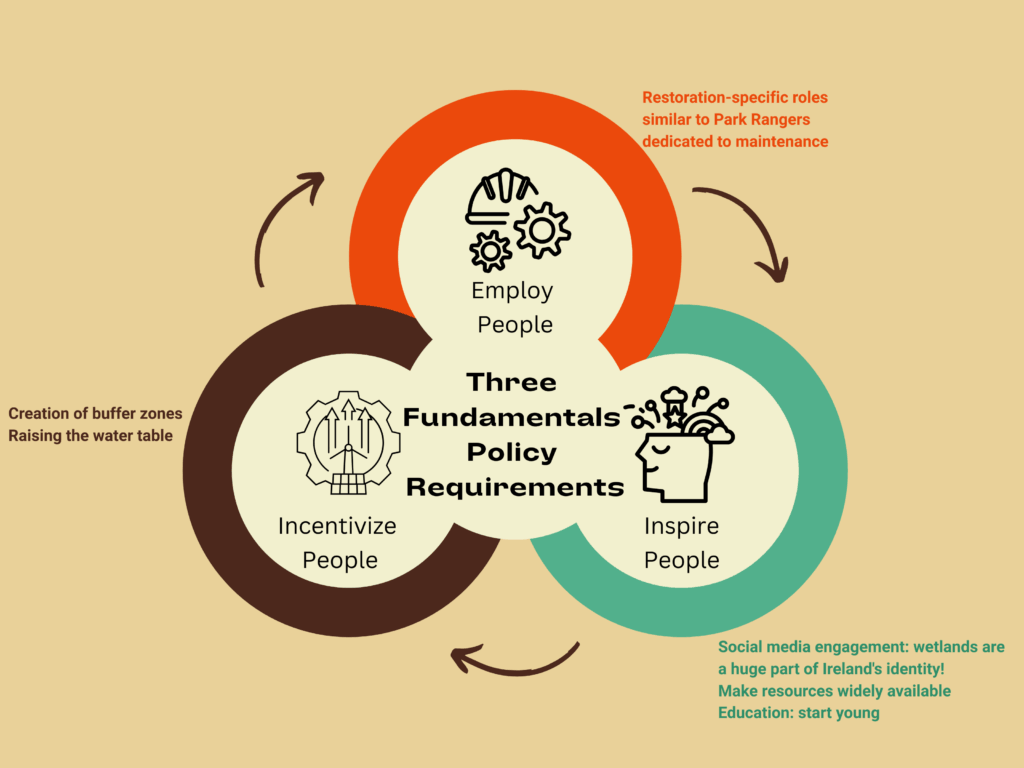

I have presented two behavioural and moral thresholds, both of which must be considered when reflecting on any policy decision relating to environmental restoration (or rehabilitation), for bogs or otherwise. We must ask ourselves: to what extent does this policy allow an individual to choose the “humble” option, to afford the environmentally beneficial choice? And further: to what extent does this policy perceive an environment as simply tolerable (or worse, a danger or a wasteland) rather than safe, interactive, and valuable in its own right?

While efforts like the Peatlands Climate Action Scheme (PCAS) that I work on are showing promising results, they face an obvious structural flaw. According to the Irish Peatland Conservation Council, as of 2022, 69% of bogs are actually privately owned.29

Remembering the principle of integral ecology, we cannot defer responsibility to the State to conserve/market bogs as a climate strategy for us. Every Irish resident is responsible for their attitudes and attentions towards the land. This will lead us to push for the right policies and pressure the government to make decisions with the lens of environmental ethics, and also motivate us to care about the little things in our very midst, and make daily decisions to the benefit of peatlands or the environment as a whole.

Carbon Storage as Baseline

Too often, “peatland policy” is collapsed into “carbon budgeting”. But carbon storage should be seen not as a goal, but as a baseline – a minimum ethical threshold. If it becomes an obvious and ubiquitous truth that we will maintain peatland carbon storage, to what further action does that lead us?

Remember, the harm we do to peatlands is latent: the impacts will unfold long after any of our current politicians or even aspiring politicians are retired. Our actions must come from a moral sensibility – one that Catholics especially should be sensitive to – to follow what is righteous, even if that pays no dividend in an electoral cycle or even over an entire career. Every day I ask myself: How will my daily action weave into the fabric of time – How am I causing a “timeprint”?

We can imagine a future where our “baselines” are environmental rather than economic. How do we move towards it? What must change so that the most important “bar” is eliminating carbon extraction from Irish soil, and our economy could serve this goal.30 This may appear as an unrealistically metaphysical approach to policy. But our beloved “business-as-usual” lacks any metaphysical weight and is even more unrealistic.

Practical Solidarity: Looking to our neighbours

Watersheds and aquifers do not respect political boundaries. Nor do invasive flora and fauna. Nor do peatlands. It’s clearly relevant to see what our neighbours in the UK are doing with their peatlands – most directly, because Northern Irish peatland action will have direct consequence on Irish peatland action, but also because with similar climate and geomorphology, in broad strokes, academic, industrial, and policy successes seen in the UK can be emulated and integrated with harmonious efforts in Ireland.

This is already being done. In the private sector, a UK company called BeadaMoss is developing

Sphagnum moss transplant technology in degraded raised bogs. Bord na Móna have partnered with them for pilot trials in the Republic.31 In the public sector, the Shared Island Community Climate Action Scheme supports ROI-NI border counties to develop cross-border projects among paired communities. This work has included peatland research and restoration but isn’t limited to this scope.32

Our neighbours not only in the UK but in mainland Europe are also exploring a new agricultural field called paludiculture.33 With the backdrop of the EU’s new Nature Restoration Law, governments across Europe will be attempting to plan enough restoration measures to tally 20% or more of a country’s land and sea area.34 Much of this land area, not only for Ireland but for our neighbours, necessarily includes agricultural land.

But the requirement for rewetting as a “restoration” measure is entirely dependent upon the definitions of both those words: what does it mean to us for a peatland to be restored?35 Why can’t farming be compatible with wetlands instead of pasture? Surely, not every farmer in Ireland considers themselves to be specifically connected to the type of farming with which they were brought up; I would bet that many have a strong connection to their land, their peatland, but are open to innovations in agriculture – a change of use. For example, some bog areas may soon be compatible with Sphagnum growth and harvesting on a regular basis, preserving the carbon store in the soil while making “use” of the moss layer only.36

Finally, our neighbourhood is made more fully global in the online/social media sphere. Those of us who are part of Generation Laudato Si’ would most likely have access to news and activities, influencers and communities, worldwide. This includes peatland-related initiatives. In this way, the youth-led initiative RePEAT deserves attention.37 Much of their work involves campaigning spread across multiple European countries to transform sentiment among the up-and- coming changemakers in the direction of

conservation and restoration. There is a joyful engagement with peatlands and their liminality

through memes, jokes, reels, along with more substantive content.38

Grounded Hope: Looking to our Grassroots Groups

I have noticed, in explaining my research to interested parties, that we are curious about the physical process of peatland restoration: blocking drains, removing invasives, planting Sphagnum, and more.39 People want involvement in the shift in use of our land, rather than simply being told to stop using our bogs entirely. Too often we might consider ourselves ruled (at least conceptually) by inaction, by holding back, rather than the responsible action involved with restoration.

But true restoration is relational: blocking drains, planting moss, building leaky dams. It is action rooted in care. Local initiatives like the Community Wetlands Forum and ReWild Wicklow demonstrate the power of communities to lead in monitoring, maintaining, and celebrating restored sites.40

Yet institutional structures often fail to support this work. Research projects may expire with their funding cycles. Maintenance phases are too rarely planned or resourced. I’d like to put forward a simple policy proposal: fund “bog rehabilitation stewards” or “restoration rangers” to maintain restoring areas, in close partnership with local groups, beyond the actions employed by Bord na Móna through their PCAS funding or academic research groups. Equip them with actionable guides such as the Blanket Bog Restoration Toolkit from WaterLANDS.41 Let stewardship be local, embodied, and sustained.

Faith communities are uniquely positioned to support this cultural shift. Environmental service is not a distraction from the Gospel, but its extension. That patch of bog on your land? Steward it as you would your cattle. Crouch down with muddy knees and examine which mosses are thriving. Service to land is

service to life.

CONCLUSION: REFRAMING POLICY THROUGH A MORAL LENS

As an early-career scientist I don’t have experience drawing up policy. I may present ideas here that are radical and difficult to roll out quickly or seamlessly. As a researcher, I am biased towards the conclusion that we need more research in the intersection of industry and peatland conservation activity – not about its feasibility but under the assumption that it is necessary.

There are some in my field who would say the minute humans tread their boots into a peatland site, conservation becomes instantly hindered, stunted, or even impossible. But the soul of Ireland is too closely linked to using peatlands to be able to transition simply to dropping one’s sleán or oftentimes one’s livelihood without seeing some new form of active participation in the land.

Instead, why don’t we consider simpler alternatives like encouraging buffer zones at the edges of private or public properties. We let people contribute in their own way, scattered across the whole country, and

innumerable good could be done – especially for water quality. Legislation could encourage this activity. Or, it could be financially incentivised. Or, it could be achieved through an appeal to the already-growing masses of volunteers in registered charities ready and willing to work for the benefit of the environment.

It is one thing to claim the rights of nature entirely apart from human interaction, and blame ourselves for inevitably spoiling any perfection displayed by pristine peatlands. It is yet another thing to acknowledge the inextricable association between humanity and Irish bogs.42 Bogs are fundamentally entangled with human activity and human culture. They contain and preserve humans, they support human infrastructure, they represent human history, and they may either aid or weaken the chances of

human survival in the face of climate change.

If the artist, Catríona Leahy, were God, she might deign to gift rural Ireland a limited- edition, unfixed photo print – one that deteriorates each time you look at it, and which you cannot refuse to own.43 This, perhaps, is the moral position we now occupy: bound to the land, unable to look away, responsible for what fades under our gaze. The chief virtue we must cultivate is self-control – to treasure the gift, while

minimising harm to it whenever possible.

Even if these peatlands may not actually remain bogs as they are scientifically defined, I can only hope to humbly present the science with integrity, explain to the public the latent truth of what we will be losing, and predict to the best of my ability what sort of world, what sort of peatlands, Irish people will come to

tolerate, tend, and perhaps even love.

Footnotes

- The term “Laudato Si’ generation” was discussed at the Catholic Youth Network for Environmental

Sustainability in Africa conference in Nairobi in 2019; a Concept Note from the proceedings was

entitled “Laudato Si’ Generation: Young People Caring for Our Common Home.” For more, see the

website at: https://generationls.com/ or the book discussing the movement: Rebecca Rathbone and

Simon Appolloni, Generation Laudato Si’ (Mulgrave, Victoria: Garratt, 2023). ↩︎ - Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ (Vatican City: Vatican, 2015), §217. ↩︎

- Carys Swanwick, ‘Society’s Attitudes to and Preferences for Land and Landscape’, Land Use Policy,

Land Use Futures, 26, no. Supplement 1 (1 December 2009): S62–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. landusepol.2009.08.025.land and landscape is deeply complex. Attitudes are reflected in behaviour, notably patterns of consumption through recreational activity, as well as in expressed preferences. Society attaches great importance to land. A large proportion of the population engages directly with it, through gardening and involvement in the management of allotments, community gardens and other public spaces. There is increasing evidence of the benefits of such engagement for individuals and communities. Society’s attitudes and preferences have traditionally been dominated by expert or professional views, which have evolved over time and now place emphasis on everyday as well as special landscapes, and on urban greenspace and green infrastructure as much as on rural landscapes. The general public also seems to value the countryside as well as parks and green spaces nearer to home. Public attitudes are shaped by a number of different factors. Age, social and economic status, ethnic origin, familiarity, place of upbringing and residence, particularly whether urban or rural, are especially significant. Perhaps most important are environmental value orientations. At present, society seems to be polarised. At one extreme are older, more affluent, better educated, more environmentally aware people, often in social grades AB, who are often the most active users of the countryside and greenspaces. At the other extreme are younger age groups, ethnic minorities, and those who are in the DE social grades, who are often much less engaged. These groups have very different values and attitudes. But most people need to access and enjoy different types of landscape at different times and for different purposes, accessing what has been called a ‘portfolio of places’ that is particular to each person. It is by no means clear how the various factors that influence people’s attitudes and preferences will play out in the future. Society may continue to become more detached from nature and landscape, and less caring about its future. Or there could be a rekindling of society’s need to engage with the land and an increased desire to ensure that all sectors of society can benefit from green spaces and rural landscapes. This is likely to

require interventions through education and campaigns to change attitudes and behaviour. Whether

such initiatives can be effective in the face of competing drivers of attitudinal and behavioural change and over what timescale, may well determine how society’s relationships with land and

landscape evolve over the next 50 years. ↩︎ - W.J. Mitsch and S.E. Jørgensen, Ecological Engineering and Ecosystem Restoration (Hoboken, NJ:

Wiley, 2004). ↩︎ - WET-PEAT is a “Peatlands and People” project, more information about which can be found at:

https://peatlandsandpeople.ie/news/ ↩︎ - Bord na Móna, ‘Bord Na Móna Peatlands Climate Action Scheme’, BNM Peatlands Climate Action Scheme, 2021, https://www.bnmpcas.ie/. ↩︎

- The blog includes an extremely helpful graphic describing peatland growth over time, where peat soils are in a darker brown seen “terrestrialising” what may once have been a glacial lake. Andy Fuller, ‘A Bog’s Life’, Notre Dame in Ireland (blog), 2022, https://www.nd.edu/stories/irelandseries/abogs-life. ↩︎

- While peatlands are valued for their archaeological heritage, learning more about our past in this

way inevitably damages peatlands when we dig up artifacts (though significantly less damage to the artifacts now that industrial extraction has ceased!). Researchers have been discussing less invasive ways to investigate archaeology for over a decade, so it’s important to think about archaeology as more than just digging! I do not have the space to do this topic justice, but you may wish to peruse UCC’s IPeAAT project as a jumping-off point: https://www.ucc.ie/en/peatlands/ ↩︎ - E. Annie Proulx, Fen, Bog, and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis (London: Fourth Estate, 2022). ↩︎

- Proulx, Chapter 3. ↩︎

- Rod Giblett, ‘Theology of Wetlands: Tolkien and Beowulf on Marshes and Their Monsters’, Green

Letters 19, no. 2 (4 May 2015): 132–43, https:// doi.org/10.1080/14688417.2015.1019910 (Though, it

must be noted that in non-peat marshes, more abundant vegetation would not have so perfectly preserved bodies for so long and the area might be better likened to a bog or fen, and bodies so well preserved would no longer be at the surface of such ecosystems, they’d be deeply

buried.) ↩︎ - A childhood nightmare-fuel for me, The Never-ending Story, features the Swamps of Sadness where

main character Atreyu loses his horse in the muck to signify a stage of depression in his journey.

Along similar lines, Dante depicts the fifth circle of Hell as a wetland in The Inferno, where the

Sullen are stuck in the River Styx written as a muddy marsh, a literal liminal space between life

and the afterlife from which many cannot move on. ↩︎ - Abbi Flint and Benjamin and Jennings, ‘Saturated with Meaning: Peatlands, Heritage and Folklore’,

Time and Mind 13, no. 3 (2 July 2020): 285, https://doi.org/10.1080/1751696X.2020.1815293. ↩︎ - See the 1957 article by Albert J. P. McCarthy, “The Irish National Electrification Scheme”, which

heavily involves peat energy: AlbertJ. P. McCarthy, ‘The Irish National Electrification Scheme’, Geographical Review 47, no. 4 (1957): 539–54, https://doi.org/10.2307/211864. ↩︎ - E. Ruuskanen, ‘Encroaching Irish Bogland Frontiers: Science, Policy and Aspirations from the 1770s

to the 1840s’, in Histories of Technology, the Environment and Modern Britain, ed. J. Agar and J.

Ward (London: UCL Press, 2018), 22–40:22. ↩︎ - Ruuskanen, 36, 38. ↩︎

- Patrick Bresnihan and Patrick Brodie, ‘Waste, Improvement and Repair on Ireland’s Peat Bogs’, in

Ecological Reparation: Repair, Remediation and Resurgence in Social and Environmental Conflict, ed.

Dimitris Papadopoulos, Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, and Maddalena Tacchetti (Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2023), 180. ↩︎ - Imagine we swap “soil fertility” with “peatland health”. Cited in: John Bellamy Foster, ‘Marx’s

Theory of Metabolic Rift: Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology’, American Journal of

Sociology 105, no. 2 (September 1999): 375, https://doi.org/10.1086/210315. ↩︎ - Foster, 379. ↩︎

- Barbara Adam and Chris Groves, ‘Futures Tended: Care and Future- Oriented Responsibility’, Bulletin

of Science, Technology & Society 31, no. 1 (1 February 2011): 17–27, https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610391237. whose existence is only

revealed many years after they were initially produced, shows that the question of our

responsibilities toward future generations is of urgent importance. However, the nature of technological societies means that they are caught in a condition of structural irresponsibility: the tools they use to know the future cannot encompass the temporal reach of their actions. This article explores how dominant legal and moral concepts are equally deficient for helping us understand what future-oriented responsibility requires. An alternative understanding of responsibility is needed, one which can be developed from phenomenological and feminist concepts of care. Care, by opening up for us an understanding of the diversity of values that are constitutive of a worthwhile life, also connects us to the future as the future of care. As such, it provides us with ethical resources that can guide us in the face of uncertainty. ↩︎ - RHA Gallery, ‘Catriona Leahy, Nature’s Own Darkroom’, RHA Gallery, 2024,

https://rhagallery.ie/events/exhibitions/catriona-leahy-natures- own-darkroom/. ↩︎ - See, for example: Simo Hayrynen, Caitriona Devery, and Aparajita Banerjee, ‘Contested Bogs in

Ireland: A Viewpoint on Climate Change Responsiveness in Local Culture’, in Culture and Climate Resilience: Perspectives from Europe, ed. Grit Martinez (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 69–96, as well as Derek Gladwin, Contentious Terrains: Boglands, Ireland, Postcolonial Gothic (Cork: Cork University Press, 2016), and, of course: Barbara Bender and Margot Winer, eds., Contested Landscapes: Movement, Exile and Place (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020). ↩︎ - Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011). ↩︎

- Janet Martin Soskice, ‘Creatio Ex Nihilo: Its Jewish and Christian Foundations’, in Creation and

the God of Abraham, ed. David Burrell et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 24–39. ↩︎ - Kallistos Ware, ‘Through Creation to the Creator’, in Toward an Ecology of Transfiguration:

Orthodox Christian Perspectives on Environment, Nature, and Creation, ed. John Chryssavgis et al. (New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2013), 93. ↩︎ - Indeed, Thomas Aquinas states in the Summa Theologica that “…some people presume to find fault with many things in the world through not seeing the reasons for their existence. For though not

requires for the furnishing of our house, these things are necessary for the perfection of the

universe”. Summa Theologica, I, q. 72, a. 1, ad 6. ↩︎ - Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, §222. ↩︎

- Pope Francis, §224. ↩︎

- Catherine O’Connell et al., ‘Peatlands and Climate Change Action Plan’ (Irish Peatland Conservation

Council, 2021), https://irishuplandsforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Peatlands-Climate-Action-Plan- 2030-Compressed.pdf Note however than in terms of total peatland area, the Coillte Forestry Service are the largest landowners, with 60% of forestry plantations on peat soil. And, when I did my own math from the National Strategy, I came up with a more specific figure—57% of peatlands are neither state-owned nor state-protected (SPA, SAC, or NHA), which can be split into 41% of raised bogs and 72% of blanket bogs. ↩︎ - The value we currently ascribe to peatlands is in their carbon storage: the soil itself that

remains underground. Anyone who touts the sequestrating power of peatlands is using buzzwords,

because it would in fact take millenia to sequester enough C-equivalents to combat the relative

outward emissions for Ireland. Ceasing further extraction at the very least mitigates these

emissions. See, for example: Nigel T. Roulet, ‘Peatlands, Carbon Storage, Greenhouse Gases, and the

Kyoto Protocol: Prospects and Significance for Canada’, Wetlands 20, no. 4 (2000): 605–15.for

example: Nigel T. Roulet, \uc0\u8216{}Peatlands, Carbon Storage, Greenhouse Gases, and the Kyoto

Protocol: Prospects and Significance for Canada\uc0\u8217{}, {\i{}Wetlands} 20, no. 4 (2000 ↩︎ - Information made public through Bord na Móna’s preliminary EDRRS Methodology Paper: Bord na Móna, ‘Methodology Paper for the Enhanced Decommissioning, Rehabilitation and Restoration on Bord Na Móna Peatlands (Preliminary Study)’, EDRRS Methodology Paper, Version 19 (Newbridge, November 2022), 63-64, 144-146, https://www.bnmpcas.ie/wpcontent/uploads/sites/18/2022/11/Methodology%20Report%20v19%20For%20issue.pdf. This initiative also been announced on the Peatlands and People website, showcasing active work on PCAS bogs: Peatlands and People, ‘Ireland’s Climate Action Catalyst’, Peatlands and People, 10 2023, https://peatlandsandpeople.ie/news/peatlands-and-people-commences-sphagnum-planting-on-raised-bogs/.

I have witnessed firsthand these measures being enacted on my research sites, though with slow success. More information about BeadaMoss can be found here: https://beadamoss.com/ . ↩︎ - Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications, ‘Hundreds of Projects Right across the Country to Receive Comm unity Climate Action Funding’, gov.ie, 16 April 2025,

https://gov.ie/en/department-of-the-environment-climate-and-communications/press-releases/hundreds-of-projects-right-across-the-country-to-receive-community-climate-action-funding/.

Examples of awards from DAERA’s end in the UK are listed in the following community blog: Paul Meade, ‘Funding Granted to Peatlands Restoration Projects as Part of Shared Island Cooperation Programme’, iCommunity (blog), 26 November 2024,

https://www.icommunityhub.org/funding-granted-to-peatlands-restoration-projects-as-part-of-shared-island-cooperation-programme/. ↩︎ - Paludiculture defined as ‘the productive land use of wet and rewetted peatlands that preserves the

peat soil and thereby minimizes CO2 emissions and subsidence.’ Wetlands International Europe, ‘A

Definition of Paludiculture in the CAP’, Wetlands International Europe (blog), 18 October 2023,

https://europe.wetlands.org/publication/what-does- paludiculture-mean-a-definition/. ↩︎ - See a summary of the law provided by Wetlands International, which also explains the specific

implications for peatlands: Amélie Tagu, ‘Historic Step for Wetlands: Nature Restoration Law Is

Adopted!’, Wetlands International Europe (blog), 17 June 2024, https://europe.wetlands.org/

historic-step-for-wetlands-nature-restoration-law-is-adopted/. ↩︎ - Mark Usher, ‘Restoration as World-Making and Repair: A Pragmatist Agenda’, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 6, no. 2 (June 2023): 1252–77, https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221107221 Because agricultural land that has not

been true bog for hundreds of years can only be “restored” relative to a historic baseline we set.

Perhaps we simply wish to restore the hydrologic integrity of the soil rather than restoring the

historically “wild” nature of the area which would make it incompatible with modern farming

interests.no. 2 (June 2023 ↩︎ - An example of this is the Winmarleigh Carbon Farm in Manchester. To nitpick on terminology,

however, I’d like to clarify that the Carbon Farm will not actively grow carbon stores (in the form

of peat soil) but simply allow for harvests on the land while retaining its current carbon store.

See more information about Winmarleigh here: The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire Manchester and North Merseyside, ‘Winmarleigh Carbon Farm’, LANCSWT, 07 2022, https://www.lancswt.org.uk/our-work/projects/peatland-restoration/winmarleigh-carbon-farm. ↩︎ - See their manifesto on their website here: RE-PEAT, ‘Manifesto’, RE- PEAT, 2024,

https://www.re-peat.earth/manifesto. ↩︎ - For example, a post from a graphic artist poking fun at the slang phrase “I got that dawg in me”:

@breezycreations5. 2024. “Look out I’m full of bog…” Instagram, May 5, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/ C6lyhJMuPtg/?img_index=1 ↩︎ - Fr. Gary Chamberland, C.S.C, of the Notre Dame-Newman Centre for Faith and Reason asked me this

directly after an address I gave about bogs, wetland restoration, and ecological theology. ‘How, actually, tangibly, is “restoration” done at scale?’ See the recording here: Bogs Are Beautiful: Reflections on the Past h*-and Future of Irish Peatlands (Dublin, 2024), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQ1SuWQs9q4. ↩︎ - See their websites: Community Wetlands Forum, ‘Inspiring Communities to Enjoy, Manage and Protect Their Wetlands for Present and Future Generations’, Community Wetlands Forum, 2023,

https://communitywetlandsforum.ie/ and ReWild Wicklow, ‘Peatland Restoration’, ReWild Wicklow,

2022, https:// rewildwicklow.ie/projects/peatland-restoration. ↩︎ - View the resource online here: Guaduneth Chico et al., ‘Blanket Bog Restoration Toolkit’

(University College Dublin: WaterLANDS, 2024). ↩︎ - And much more Catholic! ↩︎

- Caitriona Leahy, ‘Catrionaleahy.Com’, catrionaleahy.com, 2014, https://catrionaleahy.com/. ↩︎