Introduction

Among Ireland’s fourteen prisons, there are two for female prisoners: one is the Dóchas Centre, the new female prison at Mountjoy; the other is located in the oldest prison in the country still in operation, Limerick Prison, a male prison where imprisoned women are accommodated on one corridor. Both are closed prisons. Prisons of varying levels of security, including open prisons, as are available for male prisoners in Ireland, are not provided for the female prison population.

Historically, massive numbers of women were imprisoned in Ireland: in the 1800s, for example, up to 50 per cent of the prison population on the island of Ireland, some 30,000 prisoners, was female. These numbers dropped through the twentieth century, until in the 1960s there were often less than 10 women in prison in the Republic of Ireland. In 2006, the most recent year for which statistics are available, the ‘daily average’ number of women in custody was 106, as against 3,085 men in the case of men.1 The daily average number of women detained under immigration legislation was four.

However, the daily average figure does not reflect the extent of female imprisonment in any given year. In all, during 2006, 960 women were committed to prison, of whom 409 were committed under sentence.2 The wide gap between the daily average and the total number who come into custody during the year reflects the fact that a significant percentage are sentenced or held on remand for comparatively short periods of time. A ‘profile’ of the 82 women in custody on 6 December 2006 showed that 22 (27 per cent) were serving sentences of twelve months or less, and a further 19 (23 per cent) were serving a sentence that was more than twelve months but less than two years.3

Offences for which Women are Imprisoned

In the past, huge numbers were imprisoned in Ireland for drunkenness – for example, one third of the 1,000 women imprisoned in 1930 – and huge numbers were imprisoned for simple larceny. Soliciting, assault and malicious injury to property were the next most notable offences for which women were committed to prison. No more than three or four women have been committed to prison for murder or manslaughter in any year since 1930. Drug-related offences – the possession, production, cultivation, import, export, or sale and supply of drugs – only feature in the recorded offences from 1985 onwards.

Of the 409 women committed to prison under sentence in 2006, 35 were committed for ‘Offences against the Person’ (of whom, one was committed for murder, one for manslaughter and 33 for ‘Other Offences against the Person’); three were committed for ‘Offences against Property with Violence’; 157 for ‘Offences against Property without Violence’, of which 112 were for ‘theft’; 23 were sentenced for ‘Drug Offences’; 96 for ‘Road Traffic Offences’ (of which 48 were for ‘No Insurance’), and 95 for ‘Other Offences’ – which included ‘Threatening, Abusive or Insulting Behaviour in a Public Place’(20) and ‘Debtor Offences’ (11).4

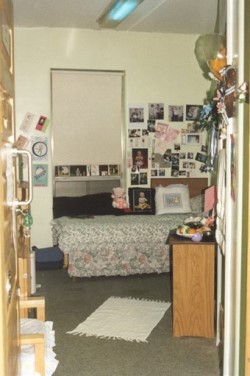

| A Room in Dóchas Centre |

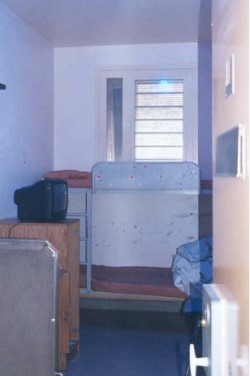

A Cell in Limerick Prison |

|

|

| In the Dóchas Centre the women live not in cells, but in rooms which are relatively spacious. All of the rooms in the Centre have private en-suite facilities. A clear window overlooks a landscaped garden with trees, shrubs, flowers, grass, and garden furniture. Note the key in the door – which the woman occupying the room holds. | The cells in Limerick women’s prison are small and cramped. Bunk beds are used to accommodate two per cell. Each cell has a metal toilet in the room: there is no provision for privacy. The window is opaque: in any case, there is nothing to look out on. Note the metal door can be opened only from the outside and only by prison guards. |

Women Prisoners in Mountjoy

Since it opened in 1858, Mountjoy Female Prison has been the largest female prison in the country. In 1956, when a borstal located in Clonmel was closed, the female prison at Mountjoy was given over to young male offenders and became St Patrick’s Institution. The small numbers of women imprisoned there at the time were moved to a basement of one wing of St Patrick’s Institution. Female prisoners continued to be detained in that basement until 1990 when, as their number began to increase, they were moved into one wing of St Patrick’s Institution. This wing, with its two showers for about forty women, continued to be used for female prisoners until 1999.

In that year, the women moved into the Dóchas Centre, the new cottage or campus style female prison within the Mountjoy Prison complex. In terms of numbers, Dóchas was designed for twice the number of female prisoners the old wing of St Patrick’s Institution could accommodate.

The Dóchas Centre holds women on remand, women awaiting sentencing, sentenced prisoners, and women detained under immigration legislation. The women are accommodated in the prison in seven separate houses, each house accommodating ten to twelve people except Cedar House, which can accommodate eighteen women, and Phoenix, the pre-release centre, which accommodates women in private rooms or in self-contained studio apartments.

Women Prisoners in Limerick

In his report of an inspection of Limerick Prison in June 2006, the Inspector of Prisons, described the women’s unit in the prison as ‘cramped, very confined and highly claustrophobic’.5 In that report and in his Annual Report for 2006–2007, the Inspector pointed out that there was almost permanent doubling up of the ten single cells of the unit in order to accommodate the twenty prisoners usually detained there. The fact that facilities were so limited, with little work or other activities provided, meant that the prisoners were ‘confined in each other’s company throughout their entire time both out of cell and … in cell’, which led to ‘tension and frustration’.6

These inadequate conditions prevail even though renovation of the unit was completed subsequent to the building of the Dóchas Centre where it was found possible to provide modern and humane living conditions and facilities.

The Regime in Women’s Prisons

Women in prison in Ireland experience prison differently, depending primarily on whether they are detained in the Dóchas Centre or in Limerick Prison.

Dóchas Centre

In the Dóchas Centre the women live in en-suite rooms. They have keys to their rooms and so can move about within the prison relatively freely. All the houses are locked at 7.30 p.m. and all the women in the prison are locked into their rooms at that time except the women in Cedar and Phoenix Houses who associate freely within their houses.

The houses and rooms are unlocked at 7.30 a.m. The women organise their own breakfasts in the kitchens of the houses. They attend school or one of the workshops or engage in one of the many activities organised in the prison. They eat lunch together with prison staff in the dining room. They go back to their occupation for the afternoon. An evening meal is served in the dining room around 5 p.m. and the women sit in the gardens or watch TV in the sitting rooms or chat and drink coffee in the kitchens until 7.30 p.m.

The prison has a good school with a very comprehensive syllabus: the range of educational and vocational opportunities offered to the women in the Dóchas Centre encompasses woodwork, computers, English and maths, cookery, food and nutrition, soft toys, pottery, art, photography, group skills, swimming, outdoor pursuits (a hillwalking opportunity, offered two or three days in the academic year), parenting, music, clay modeling, drama, physical education, creative writing. There is a beauty salon/hairdressing salon, a craft room and an industrial cleaning programme. Occasionally, a woman in the Centre undertakes an Open University course. There is an annual summer school, which I myself founded, and which is now in its eighth year.

There is a Health Care Unit staffed by nurses and a doctor with a visiting psychiatric and dental service. There is a gym and a comprehensive sport and fitness programme.

Limerick Prison

The regime in Limerick Prison could be described as a ‘lock-up’ one, with the women spending eighteen out of every twenty-four hours locked in their cells. They are called at 8 a.m. for breakfast; they pick this up in the food-servery and take it to their cells to eat and they are locked in to eat it. They are unlocked at 9 a.m. and they may attend the class that the school is providing for them, if there is such provision, or they may clean some part of the corridor or communal shower/toilet area. If they stay in their cell they are locked in. They pick up lunch at noon and are locked into their cells to eat it. If they chose to leave their cells to attend class or to clean, they are unlocked again at 2 p.m. At 4.30 p.m. they are again locked in their cells; they are released at 5.30 p. m. and locked up for the evening sometime before 7.30 p.m. The communal living area is a prefab in the yard dominated by a television and a pool table.

Different Women Experience Prison Differently

In addition to these very different structural experiences of women’s imprisonment in Ireland, different women experience prison differently. The female prison population is made up very young women, young women, more mature women and older women. Among the young women are those who have been in and out of the prison a few times. One of their main worries coming into the prison is: ‘who is there?’. They worry about agendas outside the prison being pursued within the prison.

There are older women, who have spent much of their lives in and out of prison. There are homeless women: one woman in the Dóchas Centre remarked to me that the new prison is beautiful, that there’s not much bother in it, that she ‘never got hit, never got toughed’, and she said that you don’t see fights in it anymore. But she added: ‘Being in prison is depressing, you might get a bit cleaner and fresher and be a bit better than you were when you came in but you still want the door open so that you get out.’

Among the women prisoners are those who have a chronic addiction – people addicted to cigarettes, solvents, paint, alcohol, cannabis, magic mushrooms, heroin, cocaine, rocks, ecstasy, speed, methadone – who view the prison and use the prison as a place of respite, a place where they receive care. They come into prison, recover their strength and then leave, generally to go back to whatever it was in their lives that debilitated them.

There are terribly poor, ill and damaged women in the prison and there are very strong, capable and able women within the prison. There are women in the prison serving sentences of two or threehours or days; two, three or more months; two three or more years, and there are three or four women serving very long or life sentences. One prison facility, whether the Dóchas Centre or Limerick Prison, has to manage and support all these women while the women themselves, away from their families, isolated from society and imprisoned, respond in different ways to the prison. For some, it does represent a place of respite, an opportunity for some recovery; for some, it represents, and they recognise it as representing, an educational and developmental opportunity. For all, it is a punishment. One woman said: ‘The only contact we have with the world outside is the TV, the radio and phone calls. I’ve been here three years now; I can’t really remember any more, even the family; it’s like a story now, my life’.

Notes

1. Irish Prison Service, Annual Report 2006, Longford: Irish Prison Service, Table 10, p. 16.

2. Ibid., Table 6, p. 13.

3. Ibid., Table 13, p. 17.

4. Ibid., Table 6, pp. 12–13.

5. Irish Prisons Inspectorate, Limerick Prison Inspection 19th–23rd June 2006, p. 87. (Available here )

6. The Hon. Mr. Justice Kinlen, Inspector of Prisons and Places of Detention, Fifth Annual Report of the Inspector of Prisons and Places of Detention for the Year 2006–2007, 2007, p. 65. (Available here)

Dr. Christina Quinlan was conferred with her Ph.D. in 2006. The subject of her doctoral dissertation was the experiences of women imprisoned in Ireland. Christina currently works in the Division of Population Health Sciences at the Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland.