Kevin Hargaden and Ciara Murphy

Dr Kevin Hargaden and Dr Ciara Murphy both work at the at the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, where Kevin serves as the Director and Social Theologian and Ciara is the Environmental Policy Advocate. Their forthcoming book is entitled The Parish as Oasis and will be published by Messenger Publications in summer 2022.

Introduction: The Environmental Policy Shaped Hole in Irish History

This essay is quite unlike the other pieces in this issue of Working Notes. While vast tomes can be written about housing or penal policy in Ireland or the relationship between the Church and State, little explicit material presents itself as “environmental policy” in the first decades after independence.

While it would be an exaggeration to suggest that there was no environmental policy in Ireland for these years, it would be accurate to ponder whether we would have any significant legislation or programmes were it not for membership of the European Economic Community in 1973. The newly independent State did inherit some laws that can be classified, retrospectively, as environmental. The British Fisheries Act of 1891 specifically addressed the regulation of the North Sea fishing fields but applied in general to Irish waters and to all salmon farming. In the same year, the Turbary (Ireland) Act established access rights to cutting turf from peatlands, particularly when procured by the Land Commission.

These pieces of legislation are notable for how they are clearly concerned with property and trade. It is arguably an act of creative reimagining that would read them as proto-environmental. Green activists today often lay the charge that capitalism trains us to view creation through an instrumentalised lens, such that space and the creatures within it are objects to be utilised for our profit. Pope Francis refers to this in Laudato Si’ as a “techno-economic mindset.”[1] For Francis, authentic environmentalism is identified by its reliance on “bonds of affection” to perceive our world accurately.[2] Viewing our environment not as a profit opportunity awaiting exploitation but as a Creation inviting us to learn how to love other creatures, other humans, ourselves, and even God, is not some mystical mumbo-jumbo, but a sustainable stance from which to strive for real climate and biodiversity care.[3]

This is not a vision which we will easily find in early Irish interventions on environmental matters.

While it may seem to be admirably progressive that as early as 1936, the young State passed a law outlawing whaling, the parliamentary debates do not dwell on the dignity of these magnificent mammals but on the risk whale oil may pose to the Irish butter industry.[4]

The centrality of agriculture to the economic viability of the Irish State could not be overstated. The first Minister for Agriculture, Patrick Hogan, described the economic policy of the nascent State as one of “helping the farmer who helped himself and letting the rest go to the devil.”[5] By 1926, agriculture accounted for 32 per cent of GDP and 54 per cent of workers were employed on farms or in the food processing industry.[6]

This, then, is the context in which we might consider environmental policy at the founding of the State and in subsequent decades. While prison had been a lived reality for those who made up the first Dáil and the task of improving housing was a priority for generations, an awareness of the environment apart from its economic value is hard to locate.

In this essay we will sketch the overdue emergence of environmental policy in Ireland. By environment, we mean engagements with biodiversity, environmental standards, and more recently, climate mitigation. While there is rich potential to consider the important distinctions between legislation and its implementation, for the sake of brevity they are largely conflated in this piece. We will conclude by arguing that while environmental policy – unlike housing policy, penal policy, or the relationship between church and State – does not feature a storied legacy from Ireland’s first century, but it will surely be a decisive factor in Ireland’s second century.

A Green Dawn: The Emergence of Irish Environmental Policy

Even when the State began to acknowledge the environment in explicit terms, it remained the case that this value was framed in economic terms, just like now broader than simply agriculture. Thus, An Foras Forbartha – established in the 1960s to encourage strategic development of infrastructure – wrote in 1969 of the “heritage” on hand across the country which was “being steadily whittled away.” But the reason this is lamentable is not because of the damage to the landscape or the harm to biodiversity, but because of its potential “for purposes of education and recreation … in the development of tourism and the pursuit of historical and scientific research.”[7]

Even if still rooted to an economistic understanding, the mid-century policy shift attributed to TK Whitaker and Seán Lemass did see the development of more concretely environmental legislation. The Maritime Jurisdiction Act passed in 1959 was intended to conserve the diversity and populations within the sea. The Common Agricultural Policy was established in 1962 and while it did not initially apply to Ireland, it was influential within national thinking. While still framed in terms of increasing raw yields[8] its existence was significant in broadening Irish discourse and social imagination beyond its borders and its traditional historical preoccupations.

And perhaps decisively, the role of local activist groups and the early forms of environmental NGOs must be considered.[9] Liam Leonard’s survey of those early campaigns captures their geographic and topical diversity. Whether it was the Georgian Society fighting to preserve the built integrity of Dublin’s environment, the opposition to nuclear power at Carnsore Point, the concerted campaigns against uranium mining in Donegal, or countless other local initiatives, theorised environmentalism almost seems to have arrived in Ireland as a by-product of a more visceral localism.[10] This grassroots-led arrangement can be all too easily overlooked by policy analysts as a variety of NIMBYism or as dislocated, disconnected singular, minor efforts.[11] But such participatory movements are socially vibrant, diverse, and effective.[12] They are, according to some prominent thinkers, the most likely source for “reconstructing our democracies” under the twin pressures of wealth inequality and political populism.[13]

There are cultural perspectives at play here that do not directly relate to policy and yet surely shaped it. For example, acknowledging that Ireland’s transition into Modernity was atypical, as the society urbanised, the urban areas were depopulated of non-human animals in a fashion that certainly informed growing understandings of “nature”, which too often persist as an idea whose meaning is contrasted against modern (urban) civilization.[14] The intellectual ground for “environmentalism” was, in part, cleared by a trend towards urban and suburban settlement that could imagine “nature” as apart from us, a process that Hilary Tovey long ago described as a part of a broader “cultural modernisation”.[15]

These factors – internal political shifts, activist movements, cultural changes, and wider global forces – together contribute to the emergence of an environmental policy consciousness in Irish politics, but the decisive shift surely came in 1973.

Continental Drift: The Significance of European Accession

After a decisive referendum in favour of membership of what was then known as the European Economic Community,[16] Ireland became a member of both the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). The attraction of both schemes was obvious for an economy still largely dependent on food production since it offered an income floor below which those in agriculture and fishing could not fall.

While earlier versions of CAP prioritised intensification over environmental sustainability, generating “adverse impacts on biodiversity” and on greenhouse gas emissions, the process of finding a compromise agricultural policy between the members of the European project was also a process of realising the central role that agriculture had in biodiversity protection and climate breakdown mitigation.[17] In line with the Rio Earth Summit, CAP has been repeatedly reformed in the hope of striking a balance between guaranteeing food availability within the Union while achieving sustainability.

The newest iteration of CAP, signed in December 2021, has continued in the progression away from subsidising production with increased concentration on eco-schemes. A new delivery model is a major point of difference, with each member State having increased flexibility in how they want to spend their money. Regional differences are anticipated and accepted, as long as nations can demonstrate that they are increasingly ambitious in terms of climate, biodiversity, and environmental pollution. This flexibility recognises that the one-size-fits-all model cannot work across the entire EU, where different issues call for targeted, localised action.

If done well this new CAP could put agriculture on a much needed alternative ecological path.[18]

While the Treaty of Rome of 1957 (which established what became the EU) did not mention any environmental concerns, a growing realisation that such matters warranted integrated responses grew through the 1960s. The first European action programme was adopted in 1973, the same year Ireland became a member and six more have followed.[19] It is not an exaggeration to say that Irish environmental legislation and policy cannot be understood apart from these European initiatives.

Ireland established a formal Environmental Protection Agency (1992) before the European Union (1993), but for the large part, the suite of environmental legislation that has now been developed and the accompanying implementation policies are extensively shaped by EU Directives and examples from other member States.[20] An example of the EU Habitats Directive of 1992 which mandated the preservation of rare, threatened, or endemic species or habitats. Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) are protected by this Direction, as well as a network of protected sites, referred to as the “Natura 2000” sites. In Ireland, this includes our bogs. When the Irish Government passed the Wildlife Amendment Acts in 2002, it designated particularly important habitats as “Natural Heritage Areas” (NHA) and under this legislation, 75 raised bogs and 73 blanket bogs have been given legal protection.

Expressions of this debt to the European context are often explicit. For example, in the Seanad debate on the Fisheries (Amendment) Acts of 2003 we find, John Browne, the Minister of State for the Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources explain:

The EU is anxious to secure complete ratification of the agreement by the EU and all 15 member states en bloc as early as possible so as to signal its commitment to sustainable fishing on the high seas and elsewhere. It has requested Ireland to make the necessary arrangements to progress the legislation and other measures required to enable it to ratify the agreement.[21]

It is also important to recognise the role that the EU plays in regulation of environmental legislation and policy implementation. It is conceivable that a State could pass the most finely calibrated laws and then proceed to ignore them, but the day-to-day oversight of the EU, along with the activity of the EPA, removes that possibility.[22]

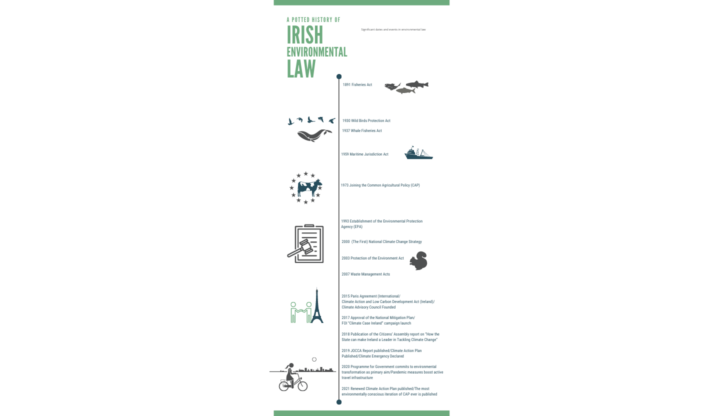

Click here to view a fullsize version of this image

Ireland now has a mature array of environmental protections covering pollution (for example, the Waste Management Acts (which were in response to the EU’s Waste Framework Directive), biodiversity protection (for example, Wildlife Amendment Act 2000), and mitigation of the climate breakdown (for example, Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Act 2021). As a rule, the State engages in public consultations which foster democratic dialogue on environmental matters. Even before the development of carbon budgets, State departments proceeded in their business with some environmental awareness.[23] While imperfect and contentious, the planning process is understood as an environmental concern, not purely an economic activity.[24]

Care of our common home is a uniquely global concern – emissions in Mumbai shape the climate reality for people in Mullingar.

And through membership of the European Union, Ireland was a signatory of international agreements. After the Rio Summit formally established environmental concerns on the global stage, the Kyoto Protocol signed in 1997 and active from 2005 committed Ireland to complying with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This brought binding obligations to measure and report on emissions and to seek to reduce them in the interests of human safety. Subsequent years brought incremental changes in global policies, but the Paris Agreement of 2015 enshrined a commitment to limit global warming to 2° Celsius.

It is important to note the dramatic shift in environmental consciousness that has occurred in the almost fifty years since Ireland joined the European project. But all the advances cannot obscure the reality that Ireland remains a “climate laggard.”[25] The Emerald Isle has a long way to go before it can claim to be properly green.

The Contemporary Moment of Hope, Even Expectation

Evidence of a positive move to a more holistic, less economistic vision for the natural environment is starting to emerge. There is a slow, albeit incomplete, shift in vision of State bodies from a purely resource-utilising perspective towards a greater understanding of the intrinsic and non-economic value of nature.

Fridays for Future Protestors outside Dáil Éireann. Photo: Used by permission of Siobhán McNamara and Gonzaga College.

State bodies, such as Bord na Móna and Coillte, which were initially established to maximise profit and create employment, are now responding to public as well as political and legislative pressure to pivot to more ecological functions. Coillte Nature[26] is a not-for-profit branch of Coillte which manages land for biodiversity and recreation not solely for timber production. Several projects, which started in 2020, are converting plantations in the Dublin mountains into biodiverse forests, restoring wetlands and bogs in the west of the country, and working to remove invasive species which will allow forests to naturally regenerate.

Bord na Móna now functions as a “climate solutions company”[27] with operations in wind generation, recycling, and peatland rehabilitation. It is almost unrecognisable from the company which up until very recently focused almost entirely on mining peat for horticulture and power generation. This undeniable shift from extraction and peat-fuelled electricity generation was accelerated by legal action taken by Friends of the Irish Environment.[28] This necessary shift has not come without criticism. The sudden pivot has resulted in huge changes in the economic landscape of the midlands, where Just Transition approaches have been sporadic, leaving communities wondering if the well worded plans will ever have substance.[29]

The ambitions to shift from laggard to… well, not-last, is also in full view in the Climate Action Plan 2021, published in November 2021, as well as the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Act 2021. These policies and legislation collectively aim to bring down our emissions by 51% by 2030, with the deadline of being net-zero by 2050. While this ambition is far beyond anything we had before in Ireland it unfortunately does not match what our fair-share contribution would be.

Notable in its wide ranging vision, the Climate Action Plan reflects the fact that climate breakdown cannot be separated from any other aspect of our lives. How we live, travel, relax, eat, and how we share our economy are all covered to some extent in this document.[30] While not perfect, with lingering hints of the cost-benefit analysis which dominated the 2019 version, we see in this iteration the progression towards a more holistic understanding of the climate and biodiversity crisis.

In this pivotal document we also see social justice issues, which have emerged over the past few years, being somewhat addressed. The carbon tax, an important tool in the climate action kit, is still listed as a key policy commitment. However, measures are outlined to alleviate the potential impact on those suffering from fuel poverty. Throughout the document complementary measures which further reduce this pressure are identified, including free and low cost retrofitting in low-income homes, retrofitting social homes, and improvements in urban and rural public transport. These measures could have been further expanded to include more widely subsidised public transport, reducing the cost for those who need it as well as more supports for those living with fuel poverty whilst in rented accommodation.

A salutary aspect of this plan is the commitment to deepening engagement of the public in a climate dialogue. Some previous attempts at engagement were exemplary, such as the Citizens Assembly from 2016 to 2018, highlighted globally as a process that should be replicated. Others have been relatively limited, such as the public consultation process proceeding the publication of the Climate Action Plan, which garnered criticism from NGOs on the limited scope for meaningful engagement.[31] But the ambition to develop these conversations while encouraging communities and citizens to partake in action should be celebrated. Climate and biodiversity action will be politically contentious. Ensuring that everyone’s voice is heard is essential to avoid technocratic creep or electoral disconnection.

The Republic of Ireland has a sophisticated environmental legislative and policy culture. It has a Green Party in government and other minority parties are striving to brand themselves as even more fundamentally committed to environmental care. It has ambitions to become a global leader in environmental care. But arguably the most significant factor in the dynamic change in this arena remains grassroots activism. Whether through “official environmentalism” represented by the broad coalition that makes up Stop Climate Chaos,[32] or citizenry science projects,[33] or countless local initiatives,[34] the energy for Irish environmentalism remains extra-legislative, more properly in the realm of active democracy. This is both a positive for environmentalism, guarding it against the temptation to view the intersecting crises we are experiencing as technical problems to be solved by experts, and positive for Irish democracy. It also remains essential for seeing the fine ambitious words found in the State’s legislation and policy programmes enacted in reality.

Conclusion: Towards a Greener Second Century

It is not the case that the Irish State only awoke to environmental concerns in the 1970s. Legislation, policy, parliamentary debates, and most importantly, the ordinary practices of citizens testified to a commitment to the care of our common home. Detailed discussions can be found in the parliamentary records that testify to the awareness of representatives and their electorate of the need to responsibly care for creation.[35] Yet it is only relatively recently that this general concern for nature began to express itself with specificity as explicit environmental legislation and policy.

In this sense, environmental policy is different from other spheres such as housing and penal policy because it was hidden inside (or even entirely swamped by) economic concerns for decades. In this essay we have argued that the decisive pivot came with membership of the European Economic Community in 1973 and that in the decades sense it has been integration with our European neighbours that has been most influential in our own care for our common home.

The present moment is marked with striking expectations that the priorities of the State will increasingly focus on these questions, which barely blipped on the radar a century ago. Purported electoral “Green waves” may have not yet arrived, but as teenagers continue on their (at the time of writing) 156th week of consecutive protests outside of Dáil Éireann, it would be a foolish analyst who would doubt that climate and biodiversity concerns will be central in Ireland’s second century. When we look back on environmental policy in the hundred years since the founding of the State, we almost have to imagine it, finding it so well camouflaged behind trade legislation or cultural commitments. But in the decades to come we will increasingly find those and other areas of our common life reorganised around the mitigation of the climate and biodiversity crisis.[36]

Footnotes: