Reality of Forced Migration: Dying to Live[1]

Eugene Quinn

Eugene Quinn is Director of the Jesuit Refugee Service, Ireland (JRS Ireland).

Introduction

Christmas is a time we associate with home, of celebration and good cheer with family and friends. The reality could not be more different for persons forcibly displaced because of a ‘well-founded fear’ of home. On the 25 December this year, UK authorities rescued 67 migrants attempting to cross the English Channel. A poignant accompanying image showed a group of refugees huddled together in white blankets and with blue surgical masks disembarking at 1.30am on Christmas morning.[2] Yet they would count themselves lucky as no lives were lost. One month earlier, 31 migrants perished after their boat sank in the Channel. It is a stark reminder of the life-threatening risks forced migrants face in search of refuge and a place of safety to call home.

Growing Displacement and Pushbacks

In the second half of 2021, the shocking and bleak reality of forced migration was almost daily in the news. The world looked on in horror at the unfolding humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan, which led to the forced displacement of millions, internally and externally, as the Taliban swept back into power. The escalation of the conflict in Tigray (Ethiopia) forced vast swathes of people to flee their homes in fear of their lives.[3] Closer to home the standoff at the Poland/Belarus border threatened the integrity of the European Union.

In October 2021, Poland’s nationalist government passed legislation authorising the ‘pushback’ of asylum seekers, in contravention of the Geneva Convention to which it is a signatory. On Poland’s eastern border with Belarus, thousands of migrants from the Middle East were repelled with water cannons and batons: “Forced to stay on a small strip of wooded no man’s land, in the freezing conditions at least 21 people died. Hundreds of others have been secretly sheltered by courageous Polish families, risking prosecution for assisting illegal immigration.”[4] One newspaper headline, ‘Trapped at Europe’s borders’, captures the plight of hundreds of thousands of forced migrants in transit countries to the east or detained in inhumane conditions in North African countries at Europe’s southern border.

The Mediterranean Sea is one of the deadliest in the world, a cemetery to more than twenty thousand forced migrants who have perished en-route to Europe in search of safety and protection over the last two decades. An estimated 12 people a day died or disappeared while trying to reach Spain in 2021. 4,404 refugees perished, included 205 children, according to Caminando Fronteras (Walking Borders). The number of deaths in 2021 was more than twice the 2,170 deaths and disappearances recorded in 2020.[5] All across Europe’s southern frontier, thousands of forced migrants have perished trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea from Libya to Italy and from Turkey to Greece.

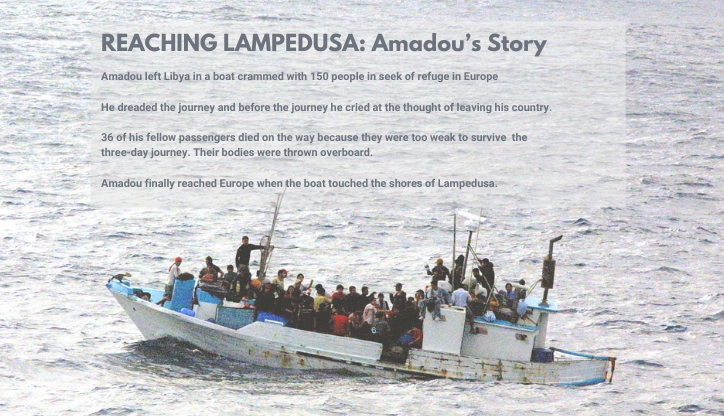

Reaching Lampedusa: Amadou’s Story

It was significant that Pope Francis chose the island of Lampedusa for his first papal visit in 2013. Pointedly, he sought to draw the world’s attention to the thousands of migrants and refugees who died trying to cross the Mediterranean in overcrowded and unsafe boats. Throughout his papacy he has condemned the “globalisation of indifference” to the fate of people fleeing violence and poverty.[6] At an event marking the fifth anniversary of the death of 800 migrants drowned at sea, the Pope urged: “This symbol of so many tragedies of the Mediterranean Sea will continue to challenge the conscience of all and encourage the growth of a more united humanity.”[7]

I am not afraid. I know that when I leave this town, I’ll do something better.

I trust myself. I know all is not lost – Jospin

Global Forced Displacement

Record Global Displacement

At the end of 2020, 82.4 million people worldwide found themselves displaced by a combination of oppression, war, generalised violence and human rights abuses (see Table 1). In the course of the past ten years the levels of forced displacement have increased dramatically, now more than double the level of a decade ago (41 million in 2010).

Excluded from these figures are potentially millions of forcibly displaced people who have not registered claims for protection or who have travelled through irregular channels, as well as ‘de-facto’ refugees fleeing life-threatening economic conditions and those displaced by natural disasters and environmental degradation who fall outside existing protection instruments.

More than one per cent – or one in 95 – of the world’s population is forcibly displaced. A high concentration of refugees live in poor and fragile contexts, and many are forced into very vulnerable situations as they flee violence and persecution, chronic poverty and hunger, and the impacts of the climate crisis. Ninety-five percent of displacement occurs in the Global South. In 2020, 86% of the world’s refugees were hosted in developing countries; with only 14% hosted in wealthier nations in the Global North.[8] By contrast, the world’s wealthiest nations, including Ireland, welcome only one in seven of refugees globally.

On the 70th anniversary of the 1951 Refugee Convention, former UN Secretary General, Ban Ki Moon, himself a former child refugee, urged wealthy states including the UK, Denmark, and Australia to rethink what he called their “punitive approach” when it comes to offering refugee protection. He rightly compared the “regressive asylum policies” of the Global North with the generosity of developing nations.[9] A gulf remains between the rights-based rhetoric of wealthier states in responding to forced migration and the restrictive practices of border control and management. Global forced displacement is at record levels and represents “the new 1%” of the world’s population, many of whom are very vulnerable and at-risk of exploitation and violence.

Refugee Producing and Hosting Regions

More than two-thirds of refugees worldwide (68%) come from five countries: The Syrian Arab Republic (6.6 million), Venezuela (4 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million), South Sudan (2.2 million) and Myanmar (1.1 million).[10] Several crises – some new, some resurfacing after years – forced people to flee within or beyond the borders of their country. Afghanistan, Somalia, and Yemen continued to be hotspots, while conflict in Syria is stretching into its tenth year.

In Ethiopia, more than one million people were displaced within the country during the year, while more than 54,000 fled the Tigray region into eastern Sudan. In northern Mozambique, hundreds of thousands escaped deadly violence, with civilians witnessing massacres by non-state armed groups in several villages, including beheadings and abductions of women and children. The outbreak of hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan left a devastating impact on civilians in both countries and displaced tens of thousands of people.

Global Impact of Covid-19

While the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on wider cross-border migration and displacement globally is not yet fully recorded, UNHCR data shows that in 2020, arrivals of new refugees and asylum-seekers were sharply down in most regions – about 1.5 million lower year on year. This meant people forcibly displaced either did not cross borders or if they could it was mainly to neighbouring countries.

Refugee resettlement programmes were particularly affected by the pandemic, border closures, and travel restrictions. Many States, including Ireland, had to cancel refugee resettlement selection missions. In 2020 only 22,270 refugees were resettled globally from a Projected Global Resettlement Need of 1.45 million places.

Global Responses to Forced Migration

International Legal Protection Framework

In the face of rising global displacement, seventy years after it signed the 1951 Refugee Convention (and the 1967 Protocol) remain the cornerstone of refugee protection. The fact there are 149 States Parties to the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol at the present time is evidence of its enduring relevance.

After World War II, the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees established the international legal basis for people seeking protection: “To be recognised legally as a refugee, an individual must be fleeing persecution on the basis of religion, race, political opinion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group, and must be outside the country of nationality.”[11] The 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees extended the scope of 1951 Refugee Convention, eliminating geographical restrictions to make the Convention truly global.

One of the major criticisms of the 1951 Convention is in relation to the definition of who is and is not a refugee; this definition reflected the experience of the preceding thirty years and especially the Second World War. Despite improvements in the 1967 Protocol, the definition remains relatively narrow, covering only people fleeing individual persecution by their governments.

Emerging drivers of global forced migration have moved beyond traditionally defined persecution, including poor governance and political instability, intra-state conflict, and environmental change and resource scarcity. A more complex and expansive interpretation of who qualifies as a refugee may be required in the face of new realities: “Lack of resources drives global forced migration by means of water shortages, unreliable food supplies, pollution, famine and climate change. These factors may not directly displace populations, but when combined with other elements, including generalised poverty, they do.”[12]

Global Protection Gap: Climate Refugees

There remains a major protection gap for people displaced across international borders by environmental factors, the so called climate refugees. Environmentally displaced persons are not covered by the 1951 Refugee Convention or the 1967 Protocol. This urgently needs to be addressed.

Climate change is the defining crisis of our time and displacement one of its most devastating consequences. On 9 August 2021, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report is a “code red for humanity”. The UN Secretary General warned “The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.”[13]

The impact of climate change may both trigger displacement and worsen living conditions or hamper return for those who have already been displaced. Limited natural resources, such as drinking water, are becoming even scarcer in many parts of the world that host refugees. Crops and livestock struggle to survive where conditions become too hot and dry, or too cold and wet, threatening livelihoods. In such conditions, climate change can exacerbate existing tensions, adding to the potential for conflicts.

UNHCR has highlighted “hazards resulting from the increasing intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, such as abnormally heavy rainfall, prolonged droughts, desertification, environmental degradation, or sea-level rise and cyclones are already causing an average of more than 20 million people to leave their homes and move to other areas in their countries each year.”[14] The World Bank estimates 200 million people could be displaced globally by 2050 because of climate change. A 2019 Resolution by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, entitled ‘A Legal Status for Climate Refugees’, calls on Member States to take “a more proactive approach to the protection of victims of natural and man-made disasters” and improve disaster preparedness mechanisms, both in Europe and in other regions.[15]

Global Compact on Refugees

Global threats to human security and safety require a global response. On 17 December 2018, the UN General Assembly affirmed the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR).[16] The main objectives of the GCR are to: ease pressures on countries that welcome and host refugees; build self-reliance of refugees; expand access to resettlement in third countries; and support conditions in countries of origin for safe return. Undoubtedly, the GCR has admirable goals and a vision to effect positive change for refugees and forcibly displaced persons worldwide. However, the challenge is to ensure the high-level commitments translate into actions that address the needs on the ground and impact positively on the lives of forced migrants and their families.

The introduction of a Global Refugee Forum every four years was welcomed as a unique opportunity to bring together different actors (States, NGOs, donors and private sector) to make pledges, share good practices, and report back on progress in implementation. The inaugural Global Refugee Forum was held in December 2019 and was seen as an opportunity for participating states to demonstrate their commitment to implementation of the GCR.[17] Significant pledges were made (including by Ireland), with 48% of pledges reported to be progressing.[18]

Potential limitations of the Global Compact include: its non-legally binding status and the absence of new or additional standards. It is a compromise text, negotiated in the knowledge some nation states were disinclined to actively increase their share of responsibility for refugees.[19] The GCR creates no new legal obligations, nor does it alter the mandate of UNHCR.[20] As was noted by the delegation of the European Union to the United Nations, the GCR is not about imposing additional burdens but rather is a reaffirmation[21] of the standards and principles contained within the UN Refugee Convention.[22]

A laudable aim of the GCR is seeking to provide a basis for predictable and equitable burden- and responsibility-sharing of refugees between states.[23] The GCR had envisaged development of a Three-Year Strategy 2019–21 on resettlement and complementary pathways in order to increase the actual number of global resettlement places and the availability of safe and legal pathways to protection.[24] Clearly though, given the inequitable distribution of refugees and forcibly displaced persons that exists today, ambitions must extend beyond mere financial support for States.[25] Otherwise, the world will remain one “in which responsibility-sharing means some states keep all the refugees and some states pay all the money.”[26]

They don’t care about you. They don’t care if you die. They don’t know you. Why should they care about you? They just want their money – Tigiste

Regional Response to Forced Displacement: Fortress Europe Returns

Regional Forced Migration Trends

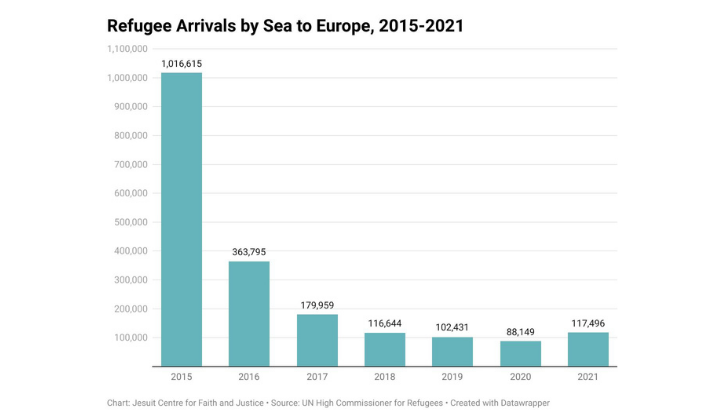

In the course of the EU Refugee Crisis there was a huge surge in the number of refugees and forced migrants accessing European territory via the Mediterranean Sea, which resulted in asylum applications reaching record levels during 2015 (1,255,640). As can be seen in Figure 2, trends in sea arrivals to Europe have dramatically changed in the intervening period, resulting in a 50% reduction since 2017.

Figure 2: Refugee Arrivals by Sea to Europe, 2015-2021

Similarly, there has been a shift in the demographics of those seeking refuge. During 2015-2017, the East Mediterranean (encompassing the Western Balkan route) route facilitated greatest access to the European territory, largely driven by the conflict in Syria. As a result, Syria consistently featured as the top country of origin in terms of arrivals by sea. Following the effective closure of the Western Balkan route as a result of the EU-Turkey deal,[27] the demographics of refugees and forced migrants arriving has significantly changed.

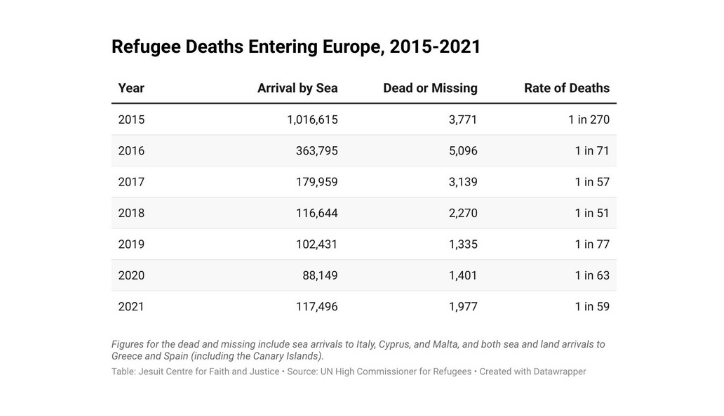

A distinguishable feature of the EU Refugee Crisis was the huge loss of life. In the period 2015-17 there was just under 12,000 deaths among 1,550,000 sea arrivals (see Table 2). Three years later the level of deaths among forced migrants entering Europe remained unacceptably high with just over 5,000 people lost at sea between 2018-20.

Although the number of deaths more than halved in the period 2018-20, the rate of deaths has more than doubled since the EU Refugee Crisis. The continued loss of life is preventable, and this reality of people dying entering Europe in search of safety and refuge is unacceptable. In the period 2015-18 EU sanctioned search and rescue operations saved 445,044 people at sea. Since then, the approach has dramatically shifted towards prioritising enforcement against migrants; engaging third countries to intercept ships; and the criminalisation of NGOs that launched their own search and rescue operations.

Forced migrants who survive the sea crossings face further barriers and challenges on arrival in the form of overcrowded, undignified, and unsafe living conditions. Until its destruction by fire in September 2020, the Moria camp on the island of Lesbos was a symbol of this European policy of deterrence and unwelcome.

(A family from Afghanistan assemble a rudimentary shelter under an olive tree on the site of the Moria Camp on Lesbos on August 21st, 2015. Credit: Stephen Ryan for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/ifrc/20819707981))

EU Pact on Migration and Asylum

In September 2020, the European Commission launched its new Pact on Migration and Asylum.[28] Labelled a “fresh start on migration,” the package of nine instruments was presented as the Commission’s new approach to migration and border management, ensuring coherence across internal and external migration policy.[29]

With this document, there was public recognition that the current asylum and migration system was not fit for purpose and that the EU and its institutions had failed to resolve the issues throughout the duration of the EU Refugee Crisis and beyond.[30] Previous reforms of the Common European Asylum System had been criticised for continuing a trend of externalisation and restriction in the European Union’s asylum policy.[31] Developments such as the EU-Turkey deal – a clear departure from Europe’s values and founding principles – further embedded the sense that protection in Europe was under threat, with the primary purpose to deny protection seekers access to Europe.

In contrast, the new EU Pact was presented as a long-term migration policy that could translate European values into practice and fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum.[32] Positively, the Pact demonstrates the European Commission’s efforts to engage in meaningful consultation with Member States.[33] Furthermore, it is welcome that it adopts a holistic approach[34] and shifts the narrative towards a positive framing of migration.[35]

Unfortunately, the negative aspects of the EU Pact identified by NGOs, academics and asylum seeker advocates far outweigh the positive elements contained within the proposals.

Critics contend the new Pact will replicate the deficient and much maligned policies of the past,[36] exacerbate the focus on externalisation of asylum, and undermine efforts to increase solidarity and responsibility sharing.[37]

There are significant concerns in relation to the heightened focus on border procedures within the new Pact. While border controls are recognised as a legitimate right of sovereign States, the strict border and return procedures outlined are criticised for undermining the right to seek asylum, offering fewer procedural rights, and creating the potential for widespread use of detention.[38]

With the ongoing application of Dublin System[39] rules and regulations, there is an increased need for a generous and binding solidarity mechanism. However, concerns have already been flagged that the relevant proposals within the new Pact will maintain the status quo whereby Member States with an external border disproportionately assume the greater responsibility for hosting new arrivals.[40]

An example of the clauses that cause such concern is the proposed flexible solidarity mechanism, which effectively will allow Member States decide how they wish to show solidarity, essentially between relocation or financial assistance.[41] This encompasses the option of “return sponsorships” – whereby a sponsoring country would facilitate the return of a rejected asylum seeker from another Member State or assume responsibility for the return from their own territory after a defined period. In this regard, Caritas Europa, in their analysis of the new Pact, highlighted the perverse scenario that facilitating return could be considered as a “solidarity” mechanism on an equal status as relocation.[42]

One of the principle aims of the new Pact is to enhance cooperation with third countries across various facets of European migration policy. However, such cooperation is controversial and contentious with the recent experiences of the EU-Turkey deal and partnership with Libya[43] casting a dark shadow.

The comprehensive, balanced and tailor-made partnerships envisaged in the new Pact are likely to be undermined by the overall focus on return and readmission within the proposals.[44] As such, concerns remain that the new Pact will continue a trend of instrumentalising overseas development aid to meet EU migration policy interests[45] and ultimately maintain a policy of externalising cost and responsibility.[46]

I have no dream. I don’t see anything, just I see that the guys who came with me on this journey…some are succeeding. They have gone and I am under the bridge. It’s hopeless – Qammar

Church Response: Welcoming the Stranger

Church Social Teaching: Forced Migration

People like Amadou should have the opportunity to remain in their homeland, support themselves and their families, and lead fulfilling lives. Their decision to emigrate should be voluntary – not one forced by fear, violence, persecution or deprivation. Creating conditions for peace requires authentic and sustainable development. Pope Francis warns “some economic rules have proved effective for growth, but not for integral human development.”[47] Global inequality in wealth, power and resources and unjust economic rules fuel conflict and forced displacement.

In his 2021 Message for the World Day of Migrants and Refugees, Francis makes an appeal “to journey together towards an ever wider ‘we’ to all men and women, for the sake of renewing the human family, building together a future of justice and peace, and ensuring that no one is left behind.” Pope Francis calls for a more inclusive response to refugees, asylum seekers, and forced migrants among us. We are offered the opportunity “to break down the walls that separate us” and “to build bridges that encourage a culture of encounter” and welcome.[48]

Populorum Progressio proposed “peace was the new name for development.”[49] The absence of peace – conflict – leads to forced displacement. But Pope Francis warns at the present time that situations of violence across the world “have become so common as to constitute a real ‘third world war’ fought piecemeal.”[50]

Rights without Border

The recent papal encyclical Fratelli Tutti calls each of us to open our hearts and to welcome the stranger in our midst. Pope Francis speaks of rights without borders. Rights are derived by virtue of our shared humanity and not our place of birth. He argues it is “unacceptable that the mere place of one’s birth or residence should result in his or her possessing fewer opportunities for a developed and dignified life.”[51]

Pope Francis refers to the nexus between development and forced migration: “Ideally, unnecessary migration ought to be avoided; this entails creating in countries of origin the conditions needed for a dignified life and integral development.”[52] He urges all to respond with openness and generosity to situations of forced migration.

The encyclical identifies concrete steps required in response to those who are fleeing grave humanitarian crises. Many of the steps are consistent with calls for positive policy change from refugee and migrant support NGOs advocating for more just and humane asylum and immigration systems in Ireland and across the world.

But the Pope warns “in some host countries, migration causes fear and alarm, often fomented and exploited for political purposes. This can lead to a xenophobic mentality, as people close in on themselves, and it needs to be addressed decisively.”[53] These attitudes leading to the ‘virus of racism’ need to be challenged through intercultural dialogue and encounter.

Integration is a two-way process. “For the communities and societies to which they come, migrants bring an opportunity for enrichment and the integral human development of all.”[54] Newly arrived migrants also need to be open to and respectful of the communities and cultures to which they have arrived. Pope Francis concludes that is why “we need to communicate with each other, to discover the gifts of each person, to promote that which unites us, and to regard our differences as an opportunity to grow in mutual respect.”[55]

Global and Local Action

The Vatican has sought to inform the development of a global response to forced migration through the publication of a 20-point action plan for governments entitled: Responding to Refugees and Migrants: Twenty Action Points.[56]

This action plan incorporates the key papal calls:

- To Welcome: Enhancing safe and legal channels for migrants and refugees. Migration should be safe, legal and orderly, and the decision to migrate voluntary.

- To Protect: Ensuring migrant and refugee rights and dignity.

- To Promote: Advancing integral human development of migrants and refugees.

- To Integrate: Enriching communities through wider participation of migrants and refugees.

The Gospel call to welcome the stranger, is directed towards local and global action in response to growing forced displacement needs across the world. In the Irish Bishop’s Conference Statement on 17 August 2021, Bishop Alan McGuckian SJ, in a statement on the Afghanistan crisis, urged the speedier processing of asylum claims for Afghan applicants and the acceptance of additional refugees in Ireland as a policy priority.

Furthermore, Bishop McGuckian SJ encouraged ongoing and proactive interventions, stating “Ireland, as one of the wealthier nations of the world, must do more for forcibly displaced people in terms of welcome and integration through State and community supports. Yes, our hearts are deeply moved by the panicked scenes of people fleeing, but it should not take such scenes and circumstances to force governments to act.”[57]

I wouldn’t leave my country if I were not desperate. I had my life and I had everything. But I didn’t feel safe anymore. I was about to lose my life. You need to hear that; you need to listen to that voice – Waleed

Conclusion

Pope Francis challenges us to welcome the stranger in our midst: “Migrants are not seen as entitled like others to participate in the life of society, and it is forgotten that they possess the same intrinsic dignity as any person…No one will ever openly deny that they are human beings, yet in practice, by our decisions and the way we treat them, we can show that we consider them less worthy, less important, less human.”[58] One concrete way that we can welcome the stranger has now been made available. The rollout of Community Sponsorship[59] in Ireland is a welcome opportunity for communities to more actively engage in the open-hearted enactment of the human fraternity that crosses all borders. This programme offers communities and parishes the opportunity to host and support a refugee family. It is a practical response on the ground that will positively impact both beneficiaries and receiving communities.

The UNHCR reported record levels of forced displacement – 82.4 million people – in 2020, double the numbers of a decade earlier. High profile crises in Afghanistan and Tigray and less visible conflicts in Yemen and Venezuela have led to ever greater numbers of men, women, and children fleeing their homes in search of safety and protection. The impact of climate change is clear and devastating for the planet and one of the consequences will be the increasing number of persons displaced from their homes due to rising sea-levels, natural disasters, and environmental degradation. By 2050 the World Bank estimates there will be up to 200 million climate refugees.

Global threats to safety require global responses. Rhetoric needs to be translated into action at global, regional and local levels. A more humane framework in response to global forced displacement is required that places the dignity of displaced persons at its centre. The personal testimony and words of Amadou, Jospin, Tigiste, Qammar, and Waleed, attest to the lived experience of forced migration and call each of us to action.

You can download a pdf of this article here

Footnotes:

[1] Danielle Vella, Dying to Live (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

[2] Press Association, “Border Force Picks up 67 People after Christmas Day Attempt to Cross Channel,” The Guardian, December 25, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/dec/25/67-people-cross-english-channel-on-christmas-day.

[3] Irish Jesuits International, “What Led to the Conflict in Tigray?,” Irish Jesuits International (blog), February 11, 2021, https://www.iji.ie/2021/02/11/what-led-to-the-conflict-in-tigray/.

[4] Guardian Editorial, “The Guardian View on Compassion for the Stranger: Not Found in Fortress Europe,” The Guardian, December 26, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/dec/26/the-guardian-view-on-compassion-for-the-stranger-not-found-in-fortress-europe.

[5] Ashifa Kassam, “Death Toll of Refugees Attempting to Reach Spain Doubles in 2021,” The Guardian, January 3, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/03/death-toll-of-refugees-attempting-to-reach-spain-doubles-in-2021.

[6] Pope Francis, “Holy Mass in the ‘Arena’ Sports Camp of Lampedusa” (Lampedusa, July 8, 2013), https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/homilies/2013/documents/papa-francesco_20130708_omelia-lampedusa.html.

[7] RTE News, “Pope Says Mediterranean Is ‘Europe’s Biggest Cemetery,’” RTE.ie, June 13, 2021, https://www.rte.ie/news/2021/0613/1227864-europe-mediterranean-migrants-pope/.

[8] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Figures at a Glance,” UNHCR, 2021, https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.

[9] Ban Ki-moon, “70 Years Ago, the World Made a Pact to Protect Refugees. Too Many of Our Leaders Are Failing to Uphold That Promise,” Time, July 26, 2021, https://time.com/6083151/1951-refugee-convention-anniversary/.

[10] UNHCR, “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2020” (Geneva, Switzerland: UN Refugee Agency, 2021), 3.

[11] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees” (United Nations, July 28, 1951), https://www.refworld.org/docid/3be01b964.html.

[12] George Palattiyil et al., “Global Trends in Forced Migration: Policy, Practice and Research Imperatives for Social Work,” International Social Work, July 28, 2021, p. 5.

[13] Office of the Secretary General of the United Nations, “Secretary-General Calls Latest IPCC Climate Report ‘Code Red for Humanity’, Stressing ‘Irrefutable’ Evidence of Human Influence,” Statements and Messages, August 9, 2021, https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20847.doc.htm.

[14] UNHCR, Climate Change and Disaster Displacement, https://www.unhcr.org/climate-change-and-disasters.html

[15] Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, “PACE – Resolution 2307 (2019) – A Legal Status for ‘Climate Refugees’” (Council of Europe, October 3, 2019), http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=28239&lang=en.

[16] United Nations, ‘Global Compact on Refugees’, A/73/12 (Part II).

[17] European Council on Refugees and Exiles, “Time to Commit: Using the Global Refugee Forum,” Policy Note (Brussels: ECRE, 2019), https://www.ecre.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Policy-Note-23.pdf.

[18] UNHCR, “Pledges & Contributions,” The Global Compact on Refugees: Digital Dashboard, 2022, https://globalcompactrefugees.org/channel/pledges-contributions.

[19] European Council on Refugees and Exiles, “Global Means Global: Europe and the Global Compact on Refugees,” Policy Note (Brussels: ECRE, 2018), https://ecre.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Policy-Note-15.pdf.

[20] Volker Türk, “The Promise and Potential of the Global Compact on Refugees,” International Journal of Refugee Law 30, no. 4 (May 18, 2019): 575–83.

[21] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Factsheet: Global Compact on Refugees” (UNHCR, December 5, 2018), https://www.unhcr.org/news/editorial/2018/12/5c10c1604/media-fact-sheet-global-compact-refugees.html.

[22] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.”

[23] See above: United Nations, “Global Compact on Refugees”, A/73/12 (Part II).

[24] UNHCR, “The Three-Year Strategy (2019-2021) on Resettlement and Complementary Pathways” (Geneva: UNHCR, 2019), https://www.unhcr.org/5d15db254.pdf.

[25] His Excellency Archbishop Ivan Jurkovič, “Past and Current Burden- and Responsibility-Sharing Arrangements” (UNHCR, July 10, 2017), https://www.unhcr.org/5968c2567.pdf.

[26] Stephanie Nebehay, “States Pledge More than $3 Billion for Refugees, Asylum Rights ‘under Threat’: U.N.,” Reuters, December 18, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-refugees-idUSKBN1YM2GT.

[27] European Council, “EU-Turkey Statement,” Council of the European Union, March 18, 2016, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/.

[28] European Commission, “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum,” COM(2020) 609 final (Brussels: European Commission, September 23, 2020), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:85ff8b4f-ff13-11ea-b44f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_3&format=PDF.

[29] European Commission, “A Fresh Start on Migration: Building Confidence and Striking a New Balance between Responsibility and Solidarity,” Text, European Commission, 09 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_1706.

[30] See above: European Commission, “A fresh start on migration: Building confidence and striking a new balance between responsibility and solidarity”, IP/20/1706.

[31] JRS Europe, “The CEAS Reform Package: The Death of Asylum by a Thousand Cuts?,” Working Paper #6 (Brussels: JRS Europe, January 2017), https://www.jrsportugal.pt/wp-content/uploads/pdf/documentos/noticias-JRS-EuropeCEASreformWorkingPaper6.pdf.

[32] Ylva Johansson, “Launching the New Pact on Migration” (Speech, Brussels, September 23, 2020), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_1733.

[33] The Catholic Church in the European Union, “Statement by the COMECE Working Group on Migration and Asylum on the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum Proposed by the European Commission” (COMECE, December 15, 2020), https://www.cbcew.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/12/COMECE-Stmt-EU-Pact-on-Migration.pdf.

[34] Christian Group, “Comments on the EU New Pact on Migration and Asylum” (Christian Group, April 13, 2021), https://ccme.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-04-13_-ChristianGroup_EU_Pact_General-Comments.pdf.

[35] Catherine Woollard, “Editorial: The Pact on Migration and Asylum: It’s Never Enough, Never, Never,” ECRE.org (blog), September 25, 2020, https://ecre.org/the-pact-on-migration-and-asylum-its-never-enough-never-never/.

[36] See above: Christian Group, “Comments on the EU new Pact on Migration and Asylum”.

[37] European Council on Refugees and Exiles, “Joint Statement: The Pact on Migration and Asylum: To Provide a Fresh Start and Avoid Past Mistakes, Risky Elements Need to Be Addressed and Positive Aspects Need to Be Expanded” (ECRE.org, June 10, 2020), https://ecre.org/the-pact-on-migration-and-asylum-to-provide-a-fresh-start-and-avoid-past-mistakes-risky-elements-need-to-be-addressed-and-positive-aspects-need-to-be-expanded/.

[38] See above: The Catholic Church in the European Union, “Statement by the COMECE Working Group on Migration and Asylum on the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum Proposed by the European Commission”.

[39] The Dublin Regulation is a European Union law that determines which EU Member State is responsible for the examination of an application for asylum, submitted by persons seeking international protection under the Geneva Convention and the EU Qualification Directive, within the European Union.

[40] See above: The Catholic Church in the European Union, “Statement by the COMECE Working Group on Migration and Asylum on the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum Proposed by the European Commission”.

[41] Donatienne Ruy and Erol Yayboke, “Deciphering the European Union’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum” (Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 29, 2020), https://www.csis.org/analysis/deciphering-european-unions-new-pact-migration-and-asylum.

[42] Caritas Europe, “Caritas Europa First Take on the New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum” (Caritas Europe, September 2020), https://www.caritas.eu/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Caritas-Europa-statement-on-EU-Pact-for-Asylum-and-Migration.pdf.

[43] NGO Joint Statement, “EU: Time to Review and Remedy Cooperation Policies Facilitating Abuse of Refugees and Migrants in Libya” (HRW, April 28, 2020), https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/28/eu-time-review-and-remedy-cooperation-policies-facilitating-abuse-refugees-and.

[44] Christian Group, “Comments on Return Policies, Readmissions and Cooperation with Third Countries within the Framework of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum” (Christian Group, April 13, 2021), https://ccme.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-04-13_-ChristianGroup_EUPact_Returns_Readmission.pdf.

[45] See above: Caritas Europa, “Caritas Europa first take on the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum”.

[45] See above: NGO Joint Statement, “Time to Review and Remedy…”.

[46] Kemal Kirişci Eminoğlu M. Murat Erdoğan, and Nihal, “The EU’s ‘New Pact on Migration and Asylum’ Is Missing a True Foundation,” Order from Chaos (blog), November 6, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/11/06/the-eus-new-pact-on-migration-and-asylum-is-missing-a-true-foundation/.

[47] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti (Assisi: Vatican, 2020), §21.

[48] Pope Francis, “Message for the 107th World Day of Migrants and Refugees, 2021” (Papal Message, World Day of Migrants and Refugees, Rome, September 26, 2021), https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/messages/migration/documents/papa-francesco_20210503_world-migrants-day-2021.html.

[49] Pope Paul VI, Populorum Progressio (Vatican: 1967), §76-77.

[50] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, §25.

[51] Pope Francis, §121.

[52] Pope Francis, §129.

[53] Pope Francis, §39.

[54] Pope Francis, §133.

[55] Pope Francis, §134.

[56] The Migrants & Refugees Section, “20 Action Points for the Global Compacts – Migrants & Refugees” (Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human, 2017), https://migrants-refugees.va/20-action-points-migrants/.

[57] Bishop Alan McGuckian, SJ, “Ireland Must Do More for Forcibly Displaced People,” Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference (blog), August 18, 2021, https://www.catholicbishops.ie/2021/08/18/bishop-mcguckian-pray-for-afghanistan-ireland-must-do-more-for-forcibly-displaced-people/.

[58] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, §39.

[59] David Stanton TD, “Community Sponsorship Ireland,” The Office for the Promotion of Migrant Integration (The Office for the Promotion of Migrant Integration, September 29, 2020), Ireland, http://www.integration.ie/en/isec/pages/community_sponsorship_ireland.