by Dr Gerard Doyle

Dr Gerard Doyle lectures in the Department of Planning and Environment, TU Dublin, and is the Programme Chair of the MSc in Local Development and Innovation. He has over 25 years experience working in the community and voluntary sector.

Introduction

Ireland’s population is forecasted to get older over the coming decades which will have implications for the care responsibilities of families and the State. While there is variance between nations, it is estimated that 30 percent of older persons across Europe lack access to quality care.[1] The situation in Ireland is particularly acute with only 1.8 formal long-term care workers per 100 persons over 65 years of age. To put that in context, in Norway, the figure is 17.1 per 100 persons.[2] Moreover, data derived from high income EU countries, including Ireland, highlight that between 56.6 percent and 90.4 percent of the population cannot access quality long term care (LTC) services due to the absence of formal LTC workers.[3]

This essay will reveal how co-operatives have the potential to make a significant contribution to addressing the above difficulties that the majority of the population encounter in securing quality long term care in Ireland. Co-ops can provide an environment for workers to gain far superior conditions than their counterparts employed in investor-owned enterprises (also referred to as capitalist enterprises). In addition, co-operatives can facilitate older people to have a greater level of control over their care, particularly in a residential setting.

Initially, the key characteristics and benefits of co-operatives will be outlined. The second section provides an overview of how co-operatives can provide a range of different services to older people to meet their needs. The third section will cover the comparative advantages of elder care co-operatives. The fourth section will examine the institutions and policy context necessary to enable co-operatives in the elder care area to be in a position to flourish. Examples from Ireland, Europe, and Japan will highlight the contribution that co-operatives can perform in the provision of quality care as well as highlight the types supports that would need to be in place.

Key characteristics and benefits of co-operatives

A co-operative is defined as ‘an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise’.[4] There are different types of co-operatives which are controlled by different types of patrons (e.g. producers, workers, consumers) or by a mix of them (multi-stakeholder co-operatives).[5]

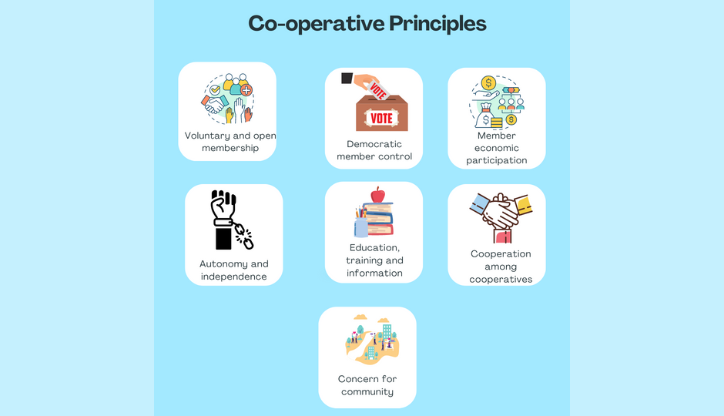

Figure 1 Seven principles which co-operatives adhere to are founded on those of the Rochdale Pioneers[6]

In essence, .[7] Accordingly, co-operatives tend to provide a more responsive service than their investor-owned counterparts.[8]

Furthermore, co-operatives generate a number of benefits arising from the aim of meeting the needs of their members. Staff conditions tend to be better, worker co-operatives tend to pay their staff (co-owners) a higher wage than employees of investor-owned enterprises in the same sector. A study of co-operatives found that worker co-operatives in Italy were more prepared to hire workers who had been long term-unemployed. They were also found to have had lower quit rates compared to conventional companies.[9] They are more resilient[10] and tend to be more efficient than investor owned companies as the level of compensation tends to provide greater incentive allied to their participatory nature.[11]

The aim and principles of co-operatives share similarities with the UN Principles for Older Persons, 1991[12] – independence, participation, care, self-fulfilment and dignity. Although, they are not binding, governments are encouraged to ensure that the above principles inform legislation and policies relating to older people. Indeed, co-operatives are an ideal organisational form to implement the actions contained in the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. In particular, their mission makes them ideal organisations for contributing to older people having equal access to health care services,[13] training of care providers, and maintaining the maximum functional capacity throughout life while promoting the full participation of older persons with disabilities.[14]

‘The power of the co-op model stems from the willingness of people of good will to work together to solve common problems. It has always done best when the beneficiaries of co-ops have been willing to use their success to help others to further their own aspirations and meet the challenges of the times through the creation of new co-ops suited to new purposes’.[15]

Services provided to older people

Co-operatives focusing on the care needs of older people can be categorised into those providing care within the home, those providing accommodation, and those engaging in member-to-member care provision.

Care within the home

Worker co-operatives and multi-stakeholder co-operatives are formed to provide care within the home. A worker co-operative is a co-operative owned and self-managed by its worker/co-owners while a multi-stakeholder co-operatives comprise stakeholders involved in the provision of elder care services.[16] Stakeholders may include beneficiaries and their families, care workers, other community members, and government representatives, among others. For a number of reasons outlined below, and in addition to the benefits highlighted above, they are effective at providing care within old peoples’ homes.[17]

Although both investor- owned care companies and worker owned care co-operatives are both concerned with the quality of the care provided, worker co-operatives are more concerned with the work conditions of the workers than their investor-owned counterparts.[18] These conditions include stable hours and schedules, medical benefits for the worker and dependents, training beyond mandatory minimums, and as worker-owners, the opportunity to participate in decision-making and in receiving a share of profits generated by the organization. Research findings from the US suggest that the worker co-operative organisational form was the key differentiator in alleviating some aspects of precarious work.[19]

Going back to the standard of care provided, research has indicated that because carers in worker co-operatives have greater control over their work environment arising from co-ownership, this leads them to being more satisfied and accordingly a superior standard of care is provided than that provided by investor-owned care providers.[20]

CASE STUDY: Great Care Co-op (GCC)

The Great Care Co-op (GCC) is Ireland’s first worker’s care co-operative. A group of migrant women govern it. With the support of the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland, the co-operative was established as a response to the exploitation migrant women were encountering in providing care to older people living in their homes. Trading since July 2020, the carers gain superior working conditions than compared to employees of investor-owned care providers. For example, carers are paid €14.50 an hour and an increased rate for working weekends. In addition, GCC provides a pension contribution to carers. GCC specialises in delivering non-clinical personal care which meets the needs of the older person and their family. The co-operative is currently providing home care in the South Dublin area and has secured a HSE service level agreement to provide home care for older people living in the Dún Laoghaire area. The plan is to replicate the model throughout Dublin and other parts of the country. By the end of 2022, GCC plans to have a team of 30 carers in place.

Accommodation

Research conducted in the UK highlights that many older people are interested in living in forms of housing which are designed and controlled by older people themselves.

Resident controlled housing for older people can take a variety of forms; it can offer a range of tenures and it can be developed in different ways. In some schemes, this involves the future residents being involved in the design and development of the housing, in others, it is about managing the housing once the residents move in. Here, however, will focus mainly on two specific types of housing, housing co-operatives and co-housing.

Housing co-operatives are housing developments that are owned and/or managed collectively by their residents. They remain a rare tenure in Ireland; unlike in Europe where it comprises around 10 percent of all housing.

They can be described as ‘tenant-ownership co-operatives’ that provide social rented housing for their members. Such co-operatives collectively own the housing and their tenants/members pay a social rent to the co-operative to cover costs. The members collectively control how the co-operative is governed. Most of them provide a combination of accommodation for families, couples and single people. Housing co-operatives can also function as care environments for older people.

CASE STUDY: Chamarel Association

The Chamarel Association, also known as the Residents’ Co-operative Housing Residence of East Lyonnais, was the first co-operative for older people in France. Located outside Lyon and established in 2010, this housing co-operative is operated for and by retirees. The facilities accommodate retirees without the personal financial means to secure housing. The co- operative was founded by two retirees who wanted to provide a safe, community-oriented space for themselves and their peers.

The co-operative values of democratic inclusion and participatory decision-making have guided the organisation since its establishment. For example, members collectively opted to serve as their own general contractors, and chose to employ eco-friendly practices and materials in the construction of the facility. Start-up funding to support the programme was secured through a 50-year bank loan paid to the co-operative founders.[1]

Co-housing is an approach to developing housing that originated in Denmark. Such housing schemes are predominately based on a purpose-built cluster of houses or apartments arranged to maximise social interaction between neighbours. Communal facilities are an integral part of co-housing schemes where residents can have a meal together or hold social events.

Co-housing emphasises resident self-management including the design phase of the scheme. When the development is completed residents manage it in a similar way to other co-operative housing schemes with a strong emphasis on collective responsibility and a commitment to participating in social activities.

These schemes can be for outright ownership, for mutual home ownership, for rent, or for a combination of these. Research highlights that co-housing is popular with older people.[22]

CASE STUDY: Older Women’s Co-housing

The Older Women’s Co-housing (OWCH) was formed, in a suburban town north of London, in 2003 as an alternative to living alone. As OWCH wished to include women who lack equity and therefore need a rent they can afford, the group looked at partnering with housing associations. The selected housing association bought the site and provided capital to construct the scheme.

Although the Housing Association financed site acquisition and construction, the prospective buyers paid 10 percent deposits. This helped reduce the risk associated with the project for the housing association. In addition, all units were sold or let before construction started. Prospective tenants were also required to make a non-refundable ‘commitment payment’ to OWCH. On completion, the housing association sold 17 homes to OWCH buyers and 8 to Housing for Women, a small housing association, for the socially rented units. Housing for Women financed this with private charitable grants, giving them greater flexibility to allocate to OWCH members.

The 2-3 bed flats are clustered around a walled garden and all have their own patio or balcony. There is a communal meeting room with kitchen with dining areas and residents share a laundry, allotment and guest room.[1]

Member-to-member health care

There are 117 health co-operatives in Japan which involve 81 hospitals, 351 medical clinics, 55 dental clinics, 227 nursing stations that provide home care, 375 home-care support centres, and 297 facilities that provide day-care services to adults. These co-operatives have total sales of 280 billion Yen[24] and employ more than 28,000 individuals. These Japanese co-operatives emphasize health promotion.[25]

In Japan, while health/nursing care services are provided through the national insurance system, preventive health care has not been adequately provided. In order to improve this situation, members of health co-operatives have engaged in voluntary preventive health practice since the 1960s. Han-groups deliver voluntary preventive health practice primarily to its members. There are 26,217 Han groups within Japan’s health co-operatives. Each Han group consists of three or more members. The members learn about diseases (cancer, diabetes, stroke, heart attack, Alzheimer’ s disease, etc.) and risk factors (stress, diet, drinking, smoking, etc.). Some Han-groups also engage in activities such as physical exercise.

At each Han-group, resident members check their blood pressure, urine and body fat with the co-operation of health care professionals allowing them to learn these skills. These trained members then provide health checks for local residents at super markets, public places, as well as health festivals organized by municipalities. As well as that health co-operatives undertake health promotional work in relation to key goals to achieve a healthy lifestyle.[26]

Comparative strengths of elder care co-operatives

Research from Canada indicates that the co-operative model of care is a source of a number of advantages in addition to the benefits which are associated with co-operatives in general:

- Democratic control provides higher levels of involvement and personal empowerment;

- The co-operative model provides a safer environment;

- Pride of ownership;

- Smaller size can mean more personal levels of care;

- The model fosters inter-generational interaction.[27]

For the purpose of this essay control and quality of care will be discussed as these are commonly cited as amongst the most important considerations when choosing care services.[28]

Control

The most prevalent benefit cited in research is that members of elder care co-operatives enjoy control over their co-operative.[29] These control rights lead to co-operative members being able to participate in the governance of the elder care service. Indeed, this is considered the most appealing feature for those involved in the different types of elder care co-operatives available, as .[30] In some cases, it facilitates the ability of older people to remain living in their community.

For older people considering a move from a single-family dwelling to a co-operative housing development, the desire to maintain a maximum degree of control over one’s environment is a paramount issue. In fact, the capacity to exercise control over housing was deemed as a key factor contributing to the high levels of satisfaction of members in a study conducted by Kansas University.[31] In addition, control rights mean that the governance structure facilitates older people having greater opportunity for social interaction with their peers, an enhanced level of personal empowerment, and a mechanism to ensure both a quality and affordable service is provided. In particular, co-operative housing enables older people to set the strategy, including long-term goals and the development of operational policies. The research undertaken by Kansas University highlighted the high levels of participation in governance. Sixty-one percent of respondents said that they were either somewhat or extremely active in the governance of their co-operative while only nine percent were not at all active. Eighty-five percent of the respondents said that the co-operatives gave them a voice in how their housing was run, while 84 percent said that co-operatives provided opportunities to work with others on common goals. This contributes to residents’ well-being.[32]

Quality of care

Elder care co-operatives provide a high quality of care as the members have the autonomy to design and deliver services without profits being transferred to investors. Moreover, the service also meets the needs of the staff (who can be worker/co-owners in the case of worker co-operatives). This assertion is also supported by a study of worker satisfaction levels within the social co-operatives of Italy.[33] In this study, the satisfaction levels of co-operative workers were higher than workers either in the public service or in investor-owned care businesses. The higher levels of satisfaction were attributable to a combination of factors including a higher degree of worker control over their work.

The health care costs associated with older people living in co-operative housing is also lower than those living in institutional settings such as nursing homes. Research attributes this to higher levels of interaction and a sense of belonging increasing their overall wellbeing.[34]

These interacting advantages of co-operatives, of control and quality of care, result in care services and facilities which are far superior for both the user and the worker. The increased level of independence and control within these services preserves the dignity of those who use them while simultaneously creating better health outcomes. Workers within these co-operatives do not have to bow to efficiencies of care to generate increased profit per unit time, allowing relationships to be generated and sustained between care workers and users.

Institutional supports

Co-operatives in the care industry are currently not the norm in Ireland and suffer from their niche position. For the potential of elder care co-operatives to be fulfilled a number of supports and initiatives would need to be implemented.[35] These include support from other co-operatives, increased awareness of co-operatives among care beneficiaries and care sector providers and greater support from the State.

Support from other co-operatives

Collaboration across the co-operative movement is required to enable and sustain co-operatives in the care sector.[36] Such collaboration takes the form of knowledge and resource sharing between co-operatives, and inclusion in consortia and other co-operative-supportive entities at the local, provincial, and national levels. Secondary-level organisations (i.e. consortia and federations) were cited as being important for new co-operatives to become financially sustainable.

CASE STUDY: Sistema Imprese Sociali

Sistema Imprese Sociali (SIS) of Milan, Italy is a consortium of 29 social co-operatives in Italy. Established in 1995, SIS aims to promote equality through a co-operative model across social sectors and among vulnerable populations in need. Of the 29 members, 15 are Type A social co-operatives, which aim to provide some sort of social service. Among the main objectives of SIS consortium are to:

-

Serve as an incubator and network hub for social co-operatives;

-

Provide consulting services;

-

Provide vocational education and training programmes for social entrepreneurs.[37]

Increased collaboration and support from co-operatives would have a myriad of benefits including easier access to financial resources from Credit Unions, increased marketing capacity when co-operatives cross-promote to each other’s membership and reducing capital expenditure if sharing resources such as physical locations.

Awareness of co-operatives among care beneficiaries and care sector providers

There are large disparities regarding public awareness of care co-operatives between and within different countries.[38] In countries and regions with a long tradition of co-operatives providing care, care beneficiaries are more familiar than countries with less of a tradition of co-operatives. Developing awareness among stakeholders is one essential means of promoting care co-operatives. Stakeholders include nurses, social workers, and medical providers but also extends to medical colleges and schools of nursing who deliver educational programmes at undergraduate and post-graduate level.[39] The inclusion of the co-operative model in syllabi would increase awareness of the advantages of care co-operatives among medical professionals who are often in a position to procure care services.

The role of the State

Access to appropriate finance is a challenge facing co-operatives.[40] The State can play a critical role in creating a benign environment for care co-operatives to flourish.

CASE STUDY: Homecare Social Economy Enterprise

Since 1997, the Quebec government has provided state support to the development of homecare co-operatives by allocating funding for these services. A grant of up to $40,000 is provided for the creation of a Homecare Social Economy Enterprise (HSEE). Another source of funding for care co-operatives and is the Programme d’exonération financière en services à domicile (PEFSAD). This is available to all Quebec residents aged over 18 which serves an incentive to citizens to use the services of care co-operatives. A basic financial contribution of $4 per hour of service is provided.

As well as access to finance, co-operatives face a number of barriers which limit their development in Ireland. Worker co-operatives are not recognised as a distinct legal entity, a minimum of seven members are currently required to create a co-operative. There are also barriers limiting the ability of businesses to transitioning to employee ownership.[41] The “Worker Co-Operatives and Right To Buy Bill 2021” brought forward in 2021 could potentially ameliorate some of these issues however it has not progressed to the Dáil as of yet. [42]

These benefits of co-operatives in the care system are clear but without widespread support from the state and, as well as the Irish society in general, co-operatives will remain a niche option for those who need it.

Conclusion

As detailed above, care co-operatives generate a number of additional benefits compared to their investor-owned counterparts. This is attributed to their aim being to meet the needs of their members as opposed to generating shareholder return. However, co-operatives encounter a number of challenges in Ireland, including lack of awareness among the public, a culture of individualism which is not disposed to co-operative enterprise, and a paucity of state supports.[43]

Therefore, social economy enterprise leaders need to, firstly, campaign for a more benign set of state policies towards co-operatives and the wider social economy enterprise sector. Secondly, they need to collaborate with the credit union movement, other co-operatives, and the trade union movement for additional resources and supports to strengthen the various sectors of social economy enterprise activity in Ireland. In particular, the establishment of a support organisation is required which would be dedicated to supporting the development of co-operatives in a number of the sectors of the Irish economy including care.

With regard to addressing the poor working conditions and sense of economic powerlessness that increasing numbers of workers in Ireland are experiencing, worker co-operatives could facilitate a proportion of the workforce to have a greater sense of control over their work environments. For this to become a reality requires that the Irish Government introduces a set of policies which would place in Ireland in line with other EU countries. Gavan and Quinlivan (2017) recommend that worker co-operatives be recognised as a distinct legal entity.[44]

Research needs to be undertaken aimed at changing policy and supporting practice towards care co-operatives.[45] Regarding the former, research should focus on the social and economic benefits of care co-operatives in addressing issues facing Irish society, and on the constraints in developing care co-operatives in Ireland. With respect to the latter, research could look at the factors that lead to their successful implementation.

The potential of care co-operatives to make a real difference in Irish society cannot be understated. This economic model is collaborative, non-exploitative and, at its core, designed to benefit the community most, would contribute to human flourishing.

Download a pdf of Co-op Care: The Case for Co-operative Care in Ireland here