John Barry

John Barry is Professor of Politics and International Relations, Queens University, Belfast

In Search of a Story

Quite a lot of the problems in our society are caused by the lack of a coherent story: for example, climate is often seen as a very scientific issue. It’s seen as something that’s going to happen in the future or somewhere else in the world, far away. It doesn’t connect with our own lived reality. Now by “our”, of course, I mean those of us who live in the white, European, privileged over-developed world. (Words matter, so I will use a few provocative terms like ‘climate breakdown’, and the ‘over developed world’ to refer to places such as where we live in Europe and North America.) Stories are really important and what I’m going to try and do in this piece is talk about some of the elements of stories that could help us understand the connection between capitalism and flows.[1]

Specifically, we will be talking about flows of migration. But capitalism is primarily about the flows of capital – you know the flows of Google, Apple, or Microsoft around the world – and why is it that it’s easier for capital and particularly large capital, such as these large multinationals to move around the world while it’s not at all easy for people? Money is happy to move people once they have been converted into the commodity known as “labour”, but persons themselves are restricted and stationary while cash is liquid and mobile. The particularly issue that concerns me is climate refugees: people displaced through no fault of their own, but because simply they are unable to inhabit and have a decent life in their place where they live (largely because of the luxuries we described as necessities in the place where we live). What I will argue is that storytelling is really important, but so is seeing that the story of the world we’re now entering in the 21st century is a world of flows. Indeed, this piece, as part of a day dedicated to studying such topics, is itself a flow of ideas. I think we’re going to need a lot more of such events, as a means of trying to figure out what the best solutions are in terms of dealing with the inevitable increase in people who are going to be displaced by climate breakdown in the years ahead.

Framing Rival Stories

The sad reality is that if we were to stop burning carbon today dramatic action is needed. If everybody in the over-developed world, for example, were to all go vegan and stopped eating beef – which is incredibly damaging to the climate in terms of the use of water and carbon energy and the production of methane by cows[2] – we have nonetheless pumped enough greenhouse gases into the climate that we have to deal with inevitable climate breakdown.[3] That means that we are going to have people in the future who are going to be displaced and part of the problem we face is, as they say, “What’s the story here?”. I’m going to give you two versions of that story.

The first is a positive story. In it, we afford people who are displaced by the climate refugee status and protection. This story replaces the status quo that there is no legal protection for those who’ve been displaced by climate reasons. So, as it stands, if you’re displaced because your government doesn’t like your ethnicity or doesn’t like your politics you can rock up to Dublin airport or Belfast or London and say, “Hi, I’m applying for refugee status because I fear persecution as a result of my religious belief, my political beliefs, or so on.” You cannot rock up to Dublin, Belfast or London and say I’m displaced, because climate breakdown has meant that the land that you used to farm is now desert. There is at present no recognition of refugee protection. Changing that is a positive story that we need to talk about.

But we also must consider the negative view: what we might call a xenophobic right wing populist view, which sadly is prevalent around Europe and North America, and against which the island of Ireland is certainly not immune. This view is held by those who are anti-immigrant, regardless of whether people are displaced by climate or displaced by other reasons. The positive partial acceptance of refugees and the negative total rejection – these are the two pathways or storylines around climate refugees.

As we gather, there is a major heat wave happening in Canada and North America, and again, it’s important how we name this. Is it a heat wave or is it evidence of a dying planet? It is interesting and edifying to pay particular attention to the news – be it RTE or the Irish Times or wherever you get your news – to see if a connection is made between climate breakdown and heat waves or other extreme weather? Think of the way when we get a really great spell of weather in Ireland it is often presented extremely positively, despite the fact that it could be an indication of the worsening climate crisis. So, how we present events is really important, because if, for example, as many as 300 people have died as a result of what’s happening in North America, there is a moral compulsion upon us to explore whether this is a climate anomaly. We can no longer be content to interpret every spell of warm weather as “Sure isn’t it great?”, [4]particularly for us who live in Ireland.

Language and framing matters in how we understand these particular issues and that’s why a good exemplar for reframing how we talk and write and communicate about climate breakdown is George Monbiot. He is probably the leading environmental journalist in the UK, writing regularly for the Guardian. A couple of years ago, he embarked on a campaign, which was successful, to get his paper The Guardian to stop writing about ‘climate change’ and to use other terms such as “global heating,” “climate crisis,” “climate breakdown.” And I think he’s quite right. Calling it climate change radically underestimates the urgency and severity of what we’re facing. As he puts it “it’s like calling an invading army unwelcome guests.”[5] We have to recognise that we’re witnessing a breakdown; an existential crisis of the life supporting systems of the planet.

Our attention can be consumed by the climate crisis, but we must not forget the simultaneous issue of equal seriousness: the biodiversity crisis. And here it is salutary to note that what we are witnessing is the planet’s sixth major mass extinction. There have been five other mass extinctions that have occurred on the planet in its evolutionary history, where up to 90% of all life has gone extinct. What’s different this time is that it’s human activity is the major driver of species going extinct and the shutting down of the life-sustaining systems of the planet.[6]

But some people say that like the boy who cried wolf, it’s too extreme to talk about the climate crisis and planetary breakdown and so on. It can be seen as a moot issue as to how we talk about this if many of our communities are often quite new to the whole issue of the planetary crisis. In such a setting, by calling it climate breakdown are we simply going too far too quickly for some people? It may put them off. Maybe you need to frame it in terms of climate change and then we can build up to talk about climate breakdown.

Reflections on how we sequence our conversation can matter. There is a danger that must be flagged here about popular understandings along the lines of infamous headlines that read “10 years to save the planet” and so on. While I can understand the moral motivation behind such appeals and their communicative simplicity, nevertheless, the planet doesn’t need saving! The planet has seen five other great mass extinction events, and there’s no reason at all to doubt that if humanity continues on the path that we’re going down that our own species could go extinct. Why do we think our species is somehow immune to the basic biophysical rules and laws that govern other parts of life on this planet? There is an issue about how we talk precisely about this topic. I do question this kind of “save the planet” narrative because what we are really aiming for is saving the planet that’s habitable for human beings to live decent lives along with their wider-than-human communities and entities. That is a better framing than simply talking about “saving the planet.”

In Praise of the Apocalypse

I do think apocalypse is an appropriate term to use in our current moment, but not in the usual way. Usually it is mistranslated and misunderstood. The word “apocalypse” has come down to us today from the ancient Greek. We imagine the apocalypse as awful. It’s “end times.” It’s death and destruction. But actually, in the ancient Greek, it means the “lifting of a veil”, thus expressing a sense of opportunity, revelation and possibly redemption and recovery.[7] One way of nicely expressing this, pertinent to wider discussions today, is that rather than see the issue of the climate breakdown as what can we do for the climate, but what we can change.

“Apocalypse”, from the Greek – ἀποκάλυψις – literally means unveiling, or revelation. It is not primarily about the end of the world, but the beginning of a new vision. (Unsplash: @dyuha)

On the one hand, there’s all of these arguments that we need to change our behaviour –influential voices will tell us we need to have geo-engineering technology, carbon capture and sequestration, and various other yet-to-be-invented marvels. This often very male solutions-focused approach imagines that we would solve the climate problem, so we’re going to do something for the climate. But having an apocalyptic framing instead prompts us to ask: “What can the climate crisis do for us?” What are the moral and cultural opportunities in terms of changing our views of the good life or of changing capitalism to something different that could be transformative? So, it’s not what we can do for the climate, which is a kind of a dominant economic-technocratic way of looking at the situation. What is required is that we inflect it with its proper moral and cultural opportunities and ask: What can we change as we respond to the climate crisis?

That is the way we should be thinking about the planetary crisis, in terms of new opportunities for rethinking the good life, rethinking human relationships with each other, rethinking human relationships with the earth, and so on at this time. Contrast this to the dominant public discussion of this issue in terms of framing it (and therefore delimiting it) to a continuation of business as usual. The effect of this is to maintain capitalism, consumerism, and our lifestyles as they are now, but perhaps drawing on renewable energy to do so. It is unlikely that that is going to be technically possible; we don’t have enough of the Earth’s resources to help us to do that, and we are going to have to radically start contemplating ideas of sufficiency, a sense of enoughness, and in particular in relation to capitalism as an economic system, to move away from the ecocidal objective of economic growth; of endless economic growth especially within the over-developed world. The challenge in those societies is not that they lack economic growth.[8] In those societies they are not experiencing a poverty problem, what these societies have is a very serious wealth problem. They have an abundance of wealth but the problem is that it’s badly, unevenly, and unjustly distributed. The challenges in societies such as ours in Ireland, for example, are those of redistribution of wealth, income, resources, and opportunities.

Moving away from growth as the main objective of economies in the minority world is necessary if we are to enable citizens in the global South to lift themselves out of poverty in an equitable and ecologically sustainable fashion. Simply put, there is not enough planet to enable us in the minority, over-developed world to continue with our high consumption ways of life and also lift people in the majority world out of poverty. And here we need to orient ourselves, to seek an unveiling in the truest apocalyptic sense, by asking disarmingly simple but powerful questions such as: Which is more important, luxuries in the global North or meeting the basic needs of those in the global South?

I think that’s fairly obvious and easy. Most of us would intuitively and unproblematically say that we should prioritise needs over luxuries and wants. However, it is wants and luxuries that constitute the endless dynamic of economic growth in the global North; a new brand of iPhone, novelties, the expansion of conveniences etc., so economic growth in our societies is NOT about meeting basic human needs. In fact, what we see in the Republic of Ireland is a serious abdication of meeting very real human needs in two dimensions, health (including mental health) and housing. That’s what our economic system should be organised around: meeting those needs rather than the endless proliferation of novelty and consumer goods that are luxuries.

Beyond Growth

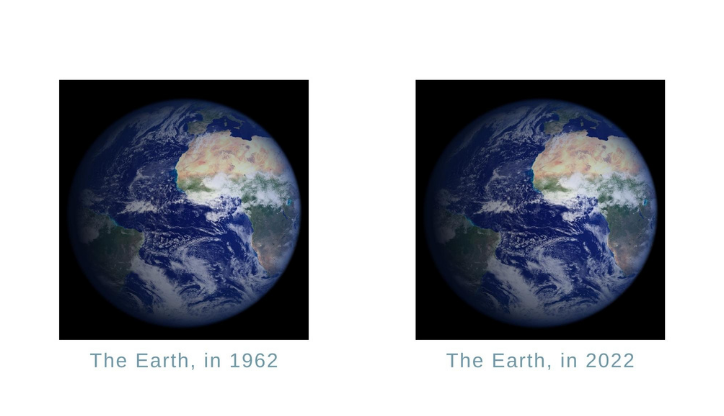

Here’s a nice visual representation of this kind of post-growth position, which is implicitly a post-capitalist position as well, because capitalism cannot be sustained if you refuse to pursue growth with no purpose beyond growth and no limit beyond what the market constrains. So, compare the two images of the Earth above, one from 1962 and the other from 2022: Can you see any difference? There is none. And the reality is the Earth isn’t growing. With the exception of solar radiation from the sun, everything that’s ever happened and will happen, at least on a terrestrial understanding of human evolution, happens within that fixed finite system of the Earth and its internal regenerative capacities of the air, the water, the seasons, and the growth and maturation and decay of life, both animal and vegetable. The human economy is a subsystem of that large earth system.

Thinking logically, how can a subsystem, which is within that fixed larger system, continually grow? It’s a bit like a balloon in a box. At some point it’s going to burst. One might even surmise it has not yet burst only because most of the growth in that balloon, the growing economy has been in the minority world and it hasn’t really been spread to the rest of the world. It is simply a reality that not everybody can live at the high levels of resource-use, pollution, water consumption and so on, as your average European or North American. There simply is not enough planet to enable this, and therefore there are strong material/scientific as well as moral arguments in favour of the redistribution of resources and the fruits of the use of those resources more equally, within the biophysical constraints of a non-growing planet.

This is the problem with growth as a permanent feature of the human economy. Nothing living grows forever, and living entities and natural systems reach a certain state, a threshold beyond which they switch to a “steady state”, or reach homeostasis, or an equilibrium state. This is true of yourself. When you become an adult, you stop growing. So why do we think that the human economy, a subsystem of the larger fixed earth system, has to or even can, keep growing endlessly and exponentially?

What is the alternative? What I would suggest is that growth should be seen as a temporary development within an economy to create and produce the goods and services, infrastructure and so on, to lift people out of poverty and give people decent lives. But then at some point, it has to move on to a steady state. To achieve this state should be seen as the goal and its achievement as a great civilisational success. In such a state, we will have a type of economy where we’re maintaining the flows of resources, restricting pollution, cultivating the communities needed to maintain and indefinitely sustain a decent way of life for everybody. But sadly, for most citizens we have this sense that growth is “normal”, it’s “natural”, and above all else is the story we are telling about how it is “needed.” We are trained to instinctively be concerned if we hear in the news that growth in the economy has declined. I think this is because for most people “growth” means “jobs”, it means good public services, investment in schools, roads and education. But what if we can have jobs and public services without growth?[9]

In the Republic of Ireland because of the neoliberal and hyper-globalised structure of our economy, it is unique in the developed world in having the strange phenomenon of “jobless growth” in recent years. So, we’ve had growth in GDP (Gross Domestic Product) because of the large foreign direct investment sector, some of those big companies I mentioned a moment ago, so it looks great on the Irish balance sheet. Growth in 2015 was 34.4%.[10] But here’s the rub: very few jobs are created as part of that increase in growth.

This prompts another question: If what we seek are sustainable jobs, why don’t we manage our economy to achieve full employment rather than creating the conditions for achieving economic growth? It is job creation that we should be focusing on, and if as a result of such job-creation policies, a bit of growth comes out of that, then all well and good. So why do our policy-makers, mainstream economists, media commentators, and most academic researchers all fixate on economic growth when we could be focusing on jobs? Why fixate on growth when we could be focusing on housing? Why fixate on growth when we could be looking at our health service? Too often our politicians and decision makers have perpetuated the myth that we need growth in order to have these good things, and that growth is the only way to have these good things. Which would you rather have – jobless growth or job-rich non-growth?

An Economy Shaped for Flourishing

A major flaw in GDP, which is the main measure of economic growth, is that it tells us nothing about the quality of life in our societies, nothing about the distribution of wealth and resources in our society and is completely amoral.[11] It is indifferent as to whether or not you have jobless growth or job-rich growth. All that matters from a GDP perspective is growth. The growth metric is amoral at the very time we need to introduce more moral and ethical thinking, both in understanding the climate and ecological crisis, but certainly also in our understanding of the economy. Again, we need to ask some very basic but profound questions here: What is the “economy”? How is it defined? What is the economy for?

We have a lot of evidence, certainly in the over-developed world of Europe and North America, that growth is no longer making us happy. Growth is no longer adding (much) to human flourishing. We have evidence in the social sciences going back to the 1970s that show people today are no happier today as they were 50 years ago.[12] This trend has been steady all that time, but on the GDP growth trend it’s been increasing (as has resource use, pollution, ecological and climate damage etc.). So, all this growth has not actually increased human levels of well-being in the overdeveloped world. Once again, we need to ask: Why are we fixating on growth as the main thing our society should be focusing on achieving, and why are we not making as our main objective the increase of human well-being? That’s the issue. Growth is a means, not an end in itself. But under capitalism, it is not just distorted to become a goal, but the primary goal. Most people do not benefit from this growth. It benefits a minority not the majority. Growth also does not help us deal with inequality. The growth metric is indifferent: all the growth of the Irish economy could accrue to 0.001% of the population only, and this, from a strict GDP point of view does not matter. Growth tells us nothing about inequality.

And growth is a structural and ineliminable – that is constitutive – component of capitalism. In this way, the capitalist economy is like a bicycle: It either “goes and grows”, or it “stalls and falls.” These are its two, and only, possible positions. It does not naturally or functionally gravitate towards a steady state. It’s got this inbuilt desire and imperative to continue to grow, so the proposition here is that if you accept that a post-growth economy is what we need to build, that also means that we are aiming at a post-capitalist economy. That does not mean to say it is a Soviet-style command-and-control economy we are proposing. What is conceived is a new thing, beyond the old stories. A capitalism that does not grow is an oxymoron. A typical capitalist economic system itself requires on average 3% growth a year just to keep stable. That sounds quite modest – just 3% a year – but think about it this way: an economy growing by 3% a year means that every 20 years or so the economy is doubling. What that means is double the pollution, double the resource use, double the production of goods and services, double the consumption of carbon energy etc.[13] And in this way we can see it is ecologically and biophysically impossible to continue with this growth rate in the long run.

Conclusion: Against Naked Emperors

As we draw our discussion to a close, we would be wise to make reference (almost obligatory now) to Greta Thunberg. I think she is a great moral heroine of our contemporary age in calling out loudly that we are in a climate crisis, and calling out the hypocrisy and cant of current mainstream and dominant media and political discussion of the issue.[14] In many ways, the period we are in now is akin to the 1930s in the run up to the Second World War, where we see a kind of “phony war” as we did then in Europe.[15] We do not yet fully recognise what’s ahead of us, or we are content to weakly acknowledge the dangers but not prepared to do what is necessary to address them.

Greta Thunberg joining with teenagers from Bristol to protest for climate action, February 28th, 2020. (1000 Words: Shutterstock 1659421072)

As a species we are facing an existential threat in the planetary crisis. We are already north of over 1°C warming across the planet. According to the Paris Agreement, the climate change agreement from 2015, the world committed to try and stay below 2°C and ideally 1.5°C. At the recent COP 26 climate conference in Glasgow in November 2021, the best our world leaders could do was “keep 1.5 alive”! It is unlikely we will make 1.5°C and, if we are being realistic and prudent, we should be thinking and planning for the very real possibility of a 2°C or 3°C warmer world.

In other words, the rhetoric from politicians and our political leaders is not being translated into the types of action that is actually needed. This is why Greta Thunberg is doing something remarkable by simply calling it as it is: The science is telling us how bad things are, why are our leaders not acting on the science? An appropriate story for our contemporary age is the boy who called out to the emperor, “you have no clothes”, The time has come to acknowledge economic growth for its own sake, as well as carbon energy and the other socio-economic causes of greenhouse gas emissions, have been stripped of their utility. They have passed the threshold so they are now sub-optimal. They increase increasing risks that far outweigh any benefits they might create.

In lieu of naked emperors, we need leaders who can respond to the story that is true. Our political class seem fixated on desperately trying to paint business-as-usual green, using terms like “green growth” and “smart growth.”[16] They want to continue with business as usual, whereas business as usual is the problem. Similar to those voices, that want to get want us to “get back to normal” after the pandemic. My view is this: Why on Earth do we want to go back to normal? Normal was the problem! Normal was ecocidal! Normal was producing inequalities! It was not adding appreciably to our lives. What is needed is a fundamental paradigm shift. Growth should be dethroned as the major objective of our economy and society. We need to flow as a global community from ‘more’ to ‘better’, and to design an economy so that good lives do not cost the earth and are not based on the exploitation of people and places.

You can download a pdf of this article here

Footnotes:

[1] Capitalism is a term that many people don’t really feel comfortable talking about. To analyse things in terms of “capital” is taken to mean that you are proposing some radical left perspective. In this context, as a political economist, I use the term simply as a description of the type of economy we live in.

[2] Hannah Ritchie, “The Carbon Footprint of Foods: Are Differences Explained by the Impacts of Methane?,” Our World in Data, March 10, 2020, https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane.

[3] John Branch and Brad Plummer, “Climate Disruption Is Now Locked In. The Next Moves Will Be Crucial.,” New York Times, September 22, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/22/climate/climate-change-future.html.

[4] Damian Carrington, “Why the Guardian Is Changing the Language It Uses about the Environment,” The Guardian, May 17, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/17/why-the-guardian-is-changing-the-language-it-uses-about-the-environment.

[5] George Monbiot, “Calling This Climate Change Is like Calling an Invading Army ‘Unexpected Visitors’ – It Is an Absurdly Passive Description of an Existential Threat. I Call It #climatebreakdown,” Tweet, @georgemonbiot (blog), July 24, 2018, https://twitter.com/georgemonbiot/status/1021694510810705920.

[6] Sam Turvey, ed., Holocene Extinctions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[7] Mike Hulme, Exploring Climate Change through Science and in Society: An Anthology of Mike Hulme’s Essays, Interviews and Speeches (London: Earthscan, from Routledge, 2013).

[8] Jason Hickel, Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (London: Windmill Books, 2021).

[9] R. Strand, Z. Kovacic, and S. Funtowicz, “Growth Without Economic Growth,” Briefing, Narratives for Change (Copenhagen: European Environment Agency, January 2021), https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/growth-without-economic-growth.

[10] Paul Krugman, “Leprechaun Economics Key to Understanding US Corporate Tax Proposal,” Irish Times, April 9, 2021, https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/leprechaun-economics-key-to-understanding-us-corporate-tax-proposal-1.4533410.

[11] Kate Raworth, “Want to Know How to Get beyond GDP? Start Here.,” Exploring Doughnut Economics (blog), July 1, 2012, https://www.kateraworth.com/2012/07/01/want-to-know-how-to-get-beyond-gdp-start-here/. See also: Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics (London: Random House Business, 2017).

[12] See, for example: Christopher P Barrington-Leigh, “Trends in Conceptions of Progress and Well-Being” (New York, NY: Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2022).

[13] With efficiencies and refinements, growth may not be matched perfectly by consumption of these resources but growth can never be decoupled entirely from these dynamics (and while there are theoretical possibilities for advances, very often in practice the relationship between growth and consumption is linear).

[14] Greta Thunberg, “The #COP26 Is over. Here’s a Brief Summary: Blah, Blah, Blah. But the Real Work Continues Outside These Halls. And We Will Never Give up, Ever.,” Tweet, @gretathunberg, November 13, 2021, https://twitter.com/gretathunberg/status/1459612735294029834.

[15] This essay was first given as an address in the summer of 2021, months before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

[16] Wolfgang Neef, “Die Stoffliche Seite Des »grünen« Kapitalismus Und Seiner Technischen Wunderwaffen Gegen Die Klimakatastrophe,” Zeitschrift Luxemburg, March 21, 2022, https://zeitschrift-luxemburg.de/artikel/die-stoffliche-seite-des-gruenen-kapitalismus-und-seiner-technischen-wunderwaffen-gegen-die-klimakatastrophe.