Ruby R. Alemu

Ruby R. Alemu holds a PhD in Theological Ethics from Aberdeen University. Her recent thesis The Cries of the Animals: Integral Ecology After Laudato Si’, explores missing nonhuman animals in the encyclical through the perspective of ‘anthropocentrism’ and the Thomistic and Franciscan influences of Laudato Si’ and Catholic Social Teaching. She has worked with Catholic Concern for Animals and Christians for Animals International in respective campaigns to advocate for nonhuman animals in Laudato Si’ initiatives.

INTRODUCTION

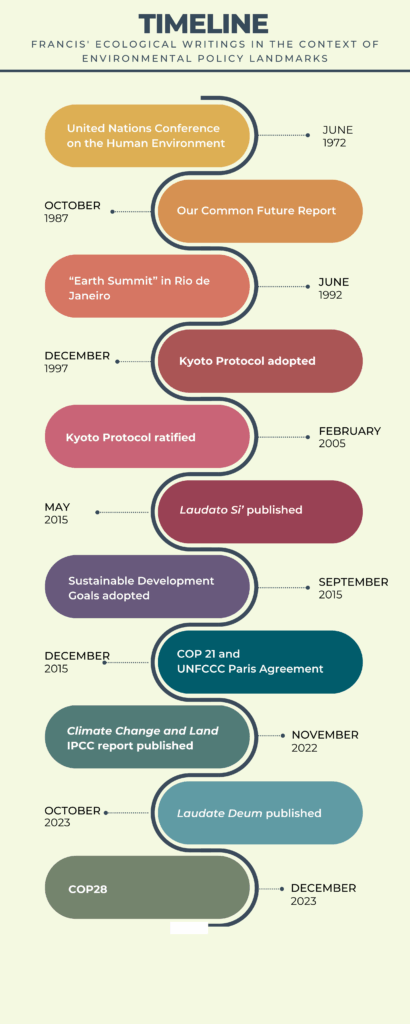

The publication of Laudate Deum in October 2023 cemented the environmental and ecological legacy of Pope Francis’ papacy. Eight years after Laudato Si’, the apostolic exhortation restates the urgency of climate change as a “global social issue and one intimately related to the dignity of human life” (LD §3). Rather than stating anything theologically new, the exhortation continues the spiritual, powerful message of Laudato Si’: it “reads as a manifesto outlining policy recommendations”1 in the run-up to COP28, as Laudato Si’ likewise – and deliberately – preceded COP21.

At a private reception for the launch of Laudate Deum in the Vatican Gardens, the author, Jonathan Safran Foer, commended the exhortation for championing individual action and emphasising the need for policy change, particularly within the global food production system:

Choosing a form of transportation

with lower carbon emissions, or reducing the consumption of animal products, especially meat, are

actions that can matter at the individual and the policy level. The power of food system change to

alter the climate is particularly noteworthy and only just beginning to be realized.2

Safran Foer’s discussion of animal agriculture hinted at the glaring omission from previous COP Summits of the global food production emergency and the lack of policy recommendations surrounding animal agriculture before COP28.3 At a theological level, however, Safran Foer’s recommendation for the serious

consideration of food system change highlights the lack of discussion in Laudate Deum of global food production and animal agriculture. His remarks also highlight the omission of animal agriculture and global food production from Laudato Si’. Specific to this conversation is the necessary reduction in meat consumption, as “without a major and urgent transformation in global meat consumption, and even if zero [greenhouse gas global emissions] in all other sectors are achieved, agriculture alone will consume the entire world’s carbon budget”,4 which is needed to keep global temperature rise under 2°C by 2050. The food that we eat and the food choices that we make are one of the – or even the most – significant actions for individuals and communities to combat the ecological crisis. Yet, both Laudato Si’ and Laudate Deum lack a single reference to meat consumption.5 This omission is glaring because of the regular appeals to scientific evidence in Laudato Si’ regarding global climate change.

BETWEEN THE CRIES: THE OMISSION OF ANIMALS IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING

Embedded as his environmental writing is within the long, systematic tradition of Catholic Social Teaching (CST), Pope Francis could not

have been expected to revolutionise ecological thought and responsibilities with a single encyclical. The modern body of social teaching is guided by contingency, continuity, change and development in order for the Church to approach socio-economic and political issues in the global context.6 In the wake of World War II, Popes such as John XXIII, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis all faced an increased frequency of new social dilemmas which the Church had to address.7 Each papal document was not an instance for revolutionary thought, but an opportunity to update the Church’s message to the modern world. The task at hand for Pope Francis

– to bring the global climate crisis into the Church’s moral concern – introduced a new methodology

to CST, by beginning from a social problem and returning to principles of CST. The significance of Laudato Si’ for Catholic ecological responsibility deserves celebration and praise 10 years on, despite the noted shortcomings in relation to individual, ethical actions.

In the lead-up to Laudate Deum in October 2023, many anticipated that it might spark a much-needed conversation about animal agriculture and the Catholic Church’s responsibility to inspire change in global food policy. The exhortation serves to remind, repeat, and update the message of integral ecology which has so characterised Pope Francis’ papacy. Whilst Laudate Deum could not propose substantially new material, the stage was set for a cursory reference to animal agriculture, or the need to assess food production and consumption behaviours. In the UK alone, two million more people in the period between Laudato Si’ and Laudate Deum adopted a vegan lifestyle. That population now represents 4.7 percent of

the population.8 The gap between Laudato Si’ in 2015 and Laudate Deum in 2023 saw a significant increase in scientific research surrounding the impact of animal agriculture on global climate change,9 including the 2019 and 2023 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports which Pope Francis references in Laudate Deum.10

As the 10th anniversary of Laudato Si’ approaches, campaigners, policy makers, theologians, and ethicists still maintain hope for the integration of animal agriculture into the integral ecology conversation. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in November last year discussed ideas for marking the 10th anniversary of Laudato Si’, and in doing so proposed a return to fasting and abstinence practices – such as meat abstinence on Fridays, a requirement which was lifted in 1966.11 The spiritual practice of fasting

and abstinence is an individual and community action which reminds human beings of their deep connections to fellow human beings, Mother Earth, and God’s creatures.

THEOLOGICAL SILENCE: ANIMALS IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHING

Two significant questions arise from these observations of missing links in Pope Francis’ papal documents: why animal agriculture has so far been omitted, and how it could be realistically incorporated at any point in the future. It seems to me that these two questions are inherently tied to a deeper issue within the body of Catholic Social Teaching: the status – and ethical treatment – of animals themselves. How can the Church address the ethical implications of animal agriculture, and its impact on the Cry of the Earth and the Poor, without first addressing the Church’s response to the very creatures at the centre of animal agriculture?

On a surface level, nonhuman animals are present in Laudato Si’ and Laudate Deum. Pope Francis draws on the influence of his namesake to recognise that the sun, moon, or any nonhuman animal is more than “an object simply to be used and controlled” (LS’ §11). Different species have “value in themselves” (§33); different creatures are valuable in God’s eyes (§69); each creature is willed, valuable, and significant (§76). Charles Camosy therefore uses the affirmation of nonhuman animal value to assess that Laudato Si’ “firmly rejects the peculiar (post) Vatican II’s emphasis on the special moral status of human beings – an emphasis which excluded moral consideration of non-human animals.”12

Yet, intrinsic worth in nonhuman creation is not a revolutionary feature of Laudato Si’: the Catechism reminds us that “animals are God’s creatures… [b]y their mere existence they bless him and give him glory.”13 The recognition of nonhuman animal value in Laudato Si’ and further back in the body of CST occurs in the context of a commitment to human priority. Where Pope Francis laments the loss of biodiversity and the intrinsic value of plants and animals (§33), this biodiversity loss “may constitute extremely important resources in the future, not only for food but also for curing disease and other uses” (§32). The loss of biodiversity is regrettable because of the effects on human beings, therefore presenting a moral concern for nonhuman animals and nonhuman creation in the context of a priority for human exceptionalism: “[t]he disappearance of a culture can be just as serious, or even more serious, than the disappearance of a species of plant or animal” (§145).

Pope Francis consistently treats animals as groups, sharing commonalities. Nonhuman animals together with human beings are all God’s creatures. Yet, nonhuman animals also belong to the wider entity of nonhuman creation, which encompasses individual creatures, ecosystems, the natural elements, and plants. The relationships which exist between human beings and nonhuman animals; between nonhuman animals and wider nonhuman creation; and between human beings and nonhuman creation are as intrinsically valuable as the value in individual beings and creation itself. The premise of Laudato Si’ in which all people of good will are called to recognise the interconnected nature of integral ecology threatens to overshadow the recognition of intrinsic value in nonhuman animals, but does not simultaneously threaten the intrinsic value of human beings because of a prior human exceptionalism.

Nonhuman animals occupy a grey space in Pope Francis’ thought. On one hand, creatures are intrinsically valuable. But the ecological tone of the encyclical which prioritises systems, entities, groups, and the relationships which exist within them, coupled with the priority of human beings in CST, places nonhuman animals at a moral disadvantage. The implicit existence of nonhuman animals under the umbrella term of the Cry of the Earth negates their particular, ontological existence as nonhuman animals. When nonhuman animals are grouped together with human animals as creatures, their differentiated ontological existence as nonhuman animals is overshadowed. Pope Francis draws on the priority of human beings “to recognize that other living beings have a value of their own in God’s eyes” (§69), yet there is a missing animal ethic from Laudato Si’ which draws on the rich Thomistic and Franciscan influences available to Pope Francis.

Whilst there are pertinent theological arguments for re-examining the place of nonhuman animals in Thomistic thought,14 it strikes me that Pope Francis displays a strong desire to be associated with not only his namesake, St Francis of Assisi, but also with the Franciscan spirituality which guides integral ecology. It was not a coincidence that the publication of Laudate Deum fell on the Feast Day of St Francis of Assisi. Both papal documents open with St Francis’ praise of creation, from the Canticle of the Sun.

However, this text by itself does not explicate a concern for nonhuman animals. Instead, nonhuman

animals are grouped together with human beings as creatures. Within the Canticle, all of creation is called to praise God, presenting the idea that each creature, each plant, each human being, and the totality of God’s creation is divinely willed and called back to God.

SAINT FRANCIS AND THE SHADOWS OF THE CANTICLE

The stories of St Francis’ encounters with nonhuman animals illuminate and strengthen the Canticle’s call to praise God. The earliest accounts of St Francis’ life demonstrate how “Francis offers an unprecedented and now timely image of human-animal relationships.”15 He encountered other animals in his life as brothers and sisters, just as he did human beings. He encounters groups of birds and fish, as well as individual animals, such as Brother Wolf. Within each encounter, there exists an allegorical and literal value. These stories teach human beings about themselves, their place, responsibility within, and relationship to God’s creation. The allegorical value which encircles hagiographical accounts of St Francis’ significance for animals, however, exists at the same time at which he himself “shows concern for

animals in themselves, in their embodied presence.”16 The first Francis valued each animal as an

intrinsically valuable creature of God, which happens to be conveying figurative meaning, rather

than valuing the figurative meaning itself.17

When we turn back to Laudato Si’, the significance of St Francis’ encounters with nonhuman animals is overshadowed by a reliance upon the Canticle and its focus on the deep connections between all of creation. The Canticle inspires the ecological method of the encyclical, to recognise the embodied fraternal and sororal (brotherly and sisterly) bonds which exist amongst creation. The “bonds of affection” which unite all creatures as brothers and sisters suggests the inclusion of animals to integral ecology. In Chapter One, Pope Francis explores the effects of climate change and global warming on biodiversity, water, land, pollution, and human beings. The section on biodiversity naturally includes nonhuman creatures who must not be viewed as mere resources, but as intrinsically valuable creatures who “give glory to God by their very existence” and convey a meaning to human beings (§33). The effects upon these nonhuman animals relate to their species survival and the consequences of extinction for other living beings. The value of nonhuman animals is therefore not primarily intrinsic, but instrumental: climactic effects on nonhuman animals impact the harmony of the created order. The value of particular nonhuman animals is secondary to the intrinsic value of relationships which connect human beings with nonhuman creation. On closer inspection, it is less than clear whether Pope Francis extends an authentic fraternity and sorority to nonhuman animals.

Pope Francis speaks of St Francis as the one who invited all of creation to enter into relationship with God: he chooses the example of St Francis preaching to the flowers, “as if they were endowed with reason,” to illustrate this (§11). Whilst this demonstrates the depths to which St Francis entered into creation, this is a remarkable oversight of St Francis’ multiple encounters with preaching to nonhuman animals: an embodied example of fraternity and sorority which depicts “a special care for and gentleness towards God’s sentient animals.”18 Where fraternal and sororal language implicitly includes nonhuman animals, explicit fraternal and sororal language does not mention animals in Laudato Si’. Pope Francis speaks about a “universal fraternity,” which is an extension of the command to love thy neighbour (§228), yet uses fraternal and sororal language to speak about exclusively human-human relationships. Human beings are united as brothers and sisters because “we have God as our common Father,” neglecting the Franciscan recognition that all things originate from God. This shared, exclusively human origin “inspires us to love and accept the wind, the sun and the clouds, even though we cannot control them” (§228). The “universal fraternity” moves from human beings directly to earthly elements: a concerning oversight of St Francis’ encounters with animals. The way in which human beings embody fraternal and sororal relationships with nature, earthly elements, or immaterial beings differs significantly from an encounter with another intrinsically valuable creature of God.

The lack of explicit engagement with nonhuman animals as brothers and sisters points towards their omission from integral ecology. Referencing the relationships which exist between human beings and nonhuman animals does not sufficiently attend to the literal, intrinsic value which drives St Francis’ lived experience of fraternal and sororal bonds with all creatures. St Francis saw in each animal a living being, freely capable of engaging with God, and his life offers an allegory for Catholics worldwide: the particular relationships which can exist between human beings and nonhuman animals do not just teach human beings about God’s creation and their place therein, but that each encounter with an animal is an encounter with an intrinsically valuable creature, capable of praising God.

A FUTURE FOR INTEGRAL ECOLOGY: NAMING THE CREATURES

The commemoration of Laudato Si’s 10-year anniversary is an opportunity for Catholic communities to strengthen their commitment to integral ecology. One way to do this would be to encourage conversations about reducing meat consumption, as mentioned at the outset of this article. Every aspect of integral ecology – animals included – suffers as a result of industrialised food production. The future of integral ecology, however, has the potential to strengthen and deepen its roots within a Franciscan (and Thomistic) theological commitment by advocating a specific moral concern for nonhuman animals. This allows human beings to deeply understand their connections within creation, but to cement the theological relationality that guides integral ecology itself. As a tradition built upon gradual change, future Catholic engagement could begin to name nonhuman animals and therefore attend to nonhuman creatures in fraternal or sororal bonds by firstly naming the injustice and violence as a consequence of human diet and animal food production systems. Instigating these conversations is a logical – and imperative – stepping stone towards furthering Catholic awareness of the global climate crisis.

Footnotes

- Martino Mazzoleni, “Pope Francis and the Environment, Act 2: Time for Decisive Climate Action,”

Environmental Politics 34, No. 1 (2025), 196. ↩︎ - Jonathan Safran Foer, ‘Farm Forward Board Member, Jonathan Safran Foer, Encourages Meat Reduction at the Vatican’, Farm Forward, 5 October 2023, https://www.farmforward.com/news/farm-forward-board-member-jonathan-safran-foer-encourages- meat-reduction-at-the-vatican/. ↩︎

- Whitney Bauck, ‘“Food Is Finally on the Table”: Cop28 Addressed Agriculture in a Real Way’, The

Guardian, 17 December 2023, sec. Environment, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/

dec/17/cop28-sustainable-agriculture-food-greenhouse-gases. ↩︎ - Nelson Iván Agudelo Higuita, Regina LaRocque, and Alice McGushin, ‘Climate Change, Industrial

Animal Agriculture, and the Role of Physicians – Time to Act’, The Journal of Climate Change and Health 13 (September 2023): 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100260. ↩︎ - Matthew Eaton and Timothy Harvie, ‘Laudato Si’ and Animal Well-Being: Food Ethics in a Throwaway

Culture’, Journal of Catholic Social Thought 17, no. 2 (2020): 241–60. ↩︎ - Gerard V. Bradley and E. Christian Brugger, ‘Contingency, Continuity, Development, and Change in

Modern Catholic Social Teaching’, in Catholic Social Teaching: A Volume of Scholarly Essays, ed. Gerard V. Bradle and E. Christian Brugger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 1. ↩︎ - Robert A. Sirico, C.S.P., ‘A Teacher Who Learns: Mater et Magistra (1961)’, in Building the Free

Society: Democracy, Capitalism, and Catholic Social Teaching, ed. George Weigel and Robert Royal

(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1993), 50. ↩︎ - Daniel Clark, ‘UK Vegan Population Increased By 1 Million In A Year, Study Finds’, Plant Based News

(blog), 26 January 2024, https:// plantbasednews.org/lifestyle/food/million-new-vegans-one-year/. ↩︎ - Şenol Çelik, ‘Bibliometric Analysis of Publications on the Effect of Animal Production on Climate

Change from Past to Present’, Frontiers in Earth Science 12 (24 May 2024): 1402407, https://doi.org/10.3389/ feart.2024.1402407. ↩︎ - Mbow, C. et al., ‘Food Security’, in Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate

Change, Desertification, Lan

d Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial

Ecosystems, ed. P.R. Shukla, et al, 1st ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022),

https://doi. org/10.1017/9781009157988. ↩︎ - Brian Roewe, ‘US Bishops Discuss Laudato Si’ for First Time in Nearly a Decade’, National Catholic

Reporter, 15 November 2024, https://www.ncronline.org/earthbeat/faith/us-bishops-discuss-laudato-si-first-time- nearly-decade. ↩︎ - Charles Camosy, ‘Locating Laudato Si’ Along a Catholic Trajectory of Concern for Animals’, Lex

Naturalis 2, no. 1 (2016): 16. ↩︎ - Catechism of the Catholic Church, §2416. ↩︎

- See: Ryan Patrick McLaughlin, ‘Thomas Aquinas’ Eco-Theological Ethics of Anthropocentric

Conservation’, Horizons 39, no. 1 (2012); Ryan Patrick McLaughlin, Christian Theology and the

Status of Animals (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Judith Barad, Aquinas on the Nature and

Treatment of Animals (London: International Scholars Publications, 1995); John Berkman, ‘Must We

Love Non-Human Animals? A Post-Laudato Si Thomistic Perspective’, New Blackfriars 102, no. 1099

(2020). ↩︎ - Susan Crane, ‘Francis of Assisi on Protecting, Obeying, and Worshiping with Animals’, Exemplaria

33, no. 4 (2021): 371. ↩︎ - Crane, 377. ↩︎

- Crane, 380. ↩︎

- Clair Linzey, Developing Animal Theology: An Engagement with Leonardo Boff (New York, NY:

Routledge, 2022), 67. ↩︎