Margaret Burns, P.J. Drudy, Rory Hearne and Peter McVerry SJ

Introduction

Providing affordable, quality and accessible housing for our people is a priority … The actions of the New Partnership Government will work to end the housing shortage and homelessness. (Programme for Government, May 2016)

Against a background of deepening public concern about the increasing number of households in Ireland experiencing some form of housing distress, and in particular the marked rise in homelessness, the Programme for a Partnership Government agreed in May 2016 set out a number of specific commitments to address the country’s housing crisis, and promised that the Minister for Housing would issue an ‘Action Plan for Housing’ within 100 days of the formation of the Government.1

That plan, Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, was published on 19 July 2016.

Rebuilding Ireland complements two earlier national plans for housing – Construction 2020 and Social Housing Strategy 2020, both published in 2014.2 It also draws on recommendations of the report, published in June 2016, of a Special Dáil Committee on Housing and Homelessness established in April 2016.

Rebuilding Ireland describes the Irish housing sector as ‘dysfunctional and under-performing’.3 In response, it sets out proposals under five ‘pillars’:

- Address homelessness;

- Accelerate social housing;

- Build more homes [in the private sector];

- Improve the rental sector;

- Utilise existing housing.

A detailed ‘Table of Actions’ was proposed to achieve these objectives, with 84 specific measures to be implemented by the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, local authorities, other government departments and state agencies, and other stakeholders. A further 29 actions were promised in a separate document, Strategy for the Rental Sector, published in December 2016.4

The proposals in Rebuilding Ireland included the establishment of a new Housing Delivery Office in the Department of Housing and a new Housing Procurement Unit within the Housing Agency. The overall implementation of the Plan is overseen by a special Cabinet Committee on Housing, chaired by An Taoiseach.5

A core commitment of the Action Plan was the promise to invest a total of €5.35 billion to secure the provision of 47,000 additional social housing units by 2021 (through a combination of new construction, acquisition and leasing from the private market, and bringing vacant social housing back into use).6

Rebuilding Ireland also provided for an investment of €200 million in a Local Infrastructure Housing Activation Fund, the purpose of which was to ‘relieve critical infrastructural blockages’ impeding the development of large private sector sites, thereby facilitating ‘substantial and affordable’ housing provision on these sites.7

The Plan also proposed that large-scale planning applications by the private sector could be made directly to An Bord Pleanála, rather than to the local authority.8

The Strategy for the Rental Sector announced the introduction of a significant new approach to regulating rents – the indentification of ‘rent pressure zones’ within which rents may not be increased by more than 4 per cent per annum for three years.9

Under the ‘banner’ of Rebuilding Ireland also, the introduction of a ‘cost rental’ scheme in Ireland is being considered, and is the subject of examination by an expert group (led by the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government) which is due to report by the end of 2017.

These and other proposals under Rebuilding Ireland are obviously intended to achieve improvement in the current housing situation; undoubtedly, many of the specific actions to be taken will bring important benefits for individuals and families who are experiencing housing difficulties.

However, the reality is that despite measures taken under Rebuilding Ireland, the incidence of homelessness, which has to be considered a key indicator of whether the housing situation is improving or not, has continued to increase: the total number of people in homeless accommodation in August 2017 was 27 per cent greater than in July 2016 when the Action Plan was published, and the number of children in such accommodation was 30 per cent greater.10

On 14 June 2017, the newly-elected Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar TD, announced in the Dáil that he had requested the Minister for Housing, Eoghan Murphy TD, to review Rebuilding Ireland within three months ‘and to consider what additional measures may be required’.11 In an address on 3 July 2017, Mr Murphy stated that what was being undertaken was not ‘a wholesale review’ and added: ‘we’re not starting from scratch again. The plan is good and is delivering important results.’12

It is in this context that this article is written. It must be obvious that the five laudable objectives in Rebuilding Ireland can be achieved in different ways. We suggest that a re-orientation of policy is warranted. The focus of this article is on achieving an appropriate philosophy of housing in Ireland and actions which reflect that philosophy. We suggest that a philosophy which emphasises ‘market forces’ as a solution to many, or most, of our housing problems, as Rebuilding Ireland currently does, will ultimately be doomed to failure. In particular, we contend that it is unrealistic to expect the private rented sector to provide a greatly increased share of the affordable, good quality and secure housing that is needed for Ireland’s growing population.

We argue further that a philosophy which overlooks the fact that housing is a human right and permits housing to be viewed as a ‘commodity’, as if it were just another instrument in the financial market, is a flawed philosophy.

Principles

The following analysis, which seeks to explore the overarching policy positions that explicitly or implicitly shape Rebuilding Ireland, is based on a number of key principles:

Housing is a human right: Housing is recognised as a fundamental human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1966), and in later UN human rights treaties which elaborate on economic and social rights as they apply to specific groups or particular situations.13 The right to housing is also recognised in the Revised European Social Charter of the Council of Europe (1999). The realisation of the right to housing is deeply intertwined with and a necessary condition for the realisation of other human rights, such as the right to life itself, the right to health, to education, to respect for family life, to privacy, to freedom from discrimination, and to participation in democratic processes.

Housing is not merely a commodity: The fact that housing is required to meet an essential need of every person, and that every person has a right to housing, means that it cannot be treated merely as a commodity, available only to those who can afford whatever is the current market price. Neither should housing be considered ‘as yet another market-place opportunity for investment, speculation and capital gain’.14

Housing policy should seek to mitigate some of the inequality arising from existing patterns of income and wealth distribution: Left to the market, access to housing and the quality and security of the housing obtained will be related to the pre-existing income and wealth of a household. In turn, the housing expenditure of a household, and the form of this expenditure (whether this is in rent or mortgage repayments), will be a significant determinant of the income available for non-housing needs, and therefore of the household’s overall standard of living, including its ability to save. Housing expenditure over the long-term will also be a key determinant of a household’s wealth – or the lack thereof. In other words, without state intervention, housing becomes a source of ever-greater inequality in terms of wealth and disposable income. Enlightened housing policies can, however, interrupt this process by ensuring good quality housing and related facilities for low-income households at a cost to those households which is related to their income.

Housing is inextricably linked to the attainment of social justice: Given the vital importance of housing in the lives of individuals, families and communities, the many ways in which housing affordability and quality can promote or hinder human flourishing, and the role which housing plays in shaping the distribution of wealth and household disposable income, it is clear that a just housing system is a prerequisite for the achievement of greater fairness in society and for the promotion of the common good.

‘Policy-free’ Narrative of Irish Housing Development

A particularly striking feature of Rebuilding Ireland is what might be termed the ‘policy-free’ narrative adopted to describe the development of the Irish housing system over recent decades.

Thus the current housing crisis is attributed solely to the country’s economic collapse and the recession,15 as if policy choices affecting housing made during and indeed prior to this period were of no relevance.

Likewise, the Plan describes the shift in the balance between market supply and public provision of housing – and the resulting reshaping of the tenure structure – in terms that simply do not recognise the role of political and policy choices:

… housing provision has moved from a model where a significant share of overall annual housing delivery was accounted for by direct provision of mainly local authority housing … to a model where housing provision has been predominantly provided by the private market …16

Elsewhere, the document refers to data which ‘illustrate the degree to which demand for social housing has been met by private landlords through a number of schemes’17, thereby managing to ignore the fact that the use of the private sector to meet social housing need could only have come about as a result of the specific policy decisions, and the associated funding allocations, made by successive governments.

The effect of this narrative – in which changes in housing with far-reaching consequences are presented as if they somehow just ‘happened’ – is to gloss over the reality that Ireland’s housing system and the current housing crisis are the result of policy choices, and of the political and ideological interests being served by those choices.

The Right to Housing

While Rebuilding Ireland recognises that housing is ‘a basic human requirement’,18 nowhere does it discuss or even mention that housing is a fundamental human right.

This omission occurs despite the fact that Ireland has ratified a range of international human rights treaties, most notably the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which include the right to housing. It is also despite the fact that, for more than a decade, there has been considerable public and political debate in Ireland about socio-economic rights, including housing, particularly in regard to the question of including such rights in the Constitution. Indeed, the May 2016 Programme for Government gave a commitment to request an Oireachtas Committee to examine this question.19

It should be noted also that the UN Committee responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has made clear that it expects states which have ratified the Covenant to prepare a national housing strategy that reflects the commitment they have given to implement the right to housing.20

The reality is, however, that Rebuilding Ireland merely follows at least ten previous national plans or statements on housing and homelessness since 1990 which have likewise ignored the question of the right to housing.21 By contrast, the National Children’s Strategy (2000)22 and the National Policy Framework for Children and Young People (2014) explicitly state that their proposed actions are intended to advance the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, with the 2014 Strategy including an overall commitment to ensure that ‘Ireland’s laws, policies and practice are compliant with the principles and provisions of the UN Convention …’.23

If it is considered appropriate that a national strategy for one area of public policy should be framed with reference to the requirements of the human rights treaty applicable in that area (a treaty which, in fact, includes the right to housing), why then are national strategies for housing developed without any reference to the right to housing set out in the human rights conventions which Ireland has ratified?

There are several dimensions of the right to housing, as outlined in international human rights law, which are of particular relevance to the current situation in Ireland and which therefore ought to have been reflected in a national action plan for housing.

For example, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has made clear that the right to housing is not fulfilled merely by the provision of some minimal form of shelter; rather, it is ‘a right to live somewhere in security, peace and dignity’.24 Three of the key characteristics of adequate housing identified by the Committee are of obvious relevance to Irish housing policy at this time: security of tenure (which has been described as a ‘cornerstone’25 of the right to housing), affordability, and adequacy in terms of structures and facilities.

Yet, in Rebuilding Ireland it is the private rented sector, the part of the Irish housing system most likely to be characterised by insecurity and high housing costs, and where regulations in respect of accommodation standards are frequently not met, which is singled out to play an increasing role in housing provision, including being used to a greater extent to meet social housing need, without substantial reforms being put in place to address these deficiencies.

Article 2.1 of the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights requires each State Party to take steps ‘to the maximum of its available resources’ towards ‘achieving progressively the full realization’ of the rights (including the right to housing) recognised in the Covenant.

The concept of ‘progressive realisation’ reflects a recognition that while states may not be in a position to immediately implement socio-economic rights in full, they are nonetheless expected to make consistent progress towards that goal. In the case of housing in Ireland, however, what has occurred over the past two decades is not progressive realisation but significant retrogression. This was evident during the economic boom when the number of households on waiting lists for social housing doubled and house prices escalated out the reach of increasing numbers of people. The situation has, of course, deteriorated considerably since then, to the point where Ireland now has its highest-ever level of recorded homelessness as well as record numbers of households on social housing waiting lists (to instance just two of the many features of the current housing crisis).

The concept of ‘maximum available resources’ reflects a concern that States Parties to the Covenant should give due priority to the realisation of socio-economic rights, including during times of economic difficulty. Rebuilding Ireland commits €5.5 billion to social housing and housing infrastructure in the period up to 2021 – but no analysis is advanced to show that this constitutes the limit of the amount the State could provide in response to the grave housing situation facing the country.

Furthermore, it should be noted that the concept of ‘maximum available resources’ includes an obligation on States Parties to ensure that public resources for the realisation of rights are allocated in a manner that is both effective and efficient.26 A number of features of the Action Plan are open to question on these grounds, including the selling-off of public land for private housing development and the determination not just to continue but to expand the open-ended subsidisation of rents in the private rented sector, instead of directly providing social housing.

Target 11.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the ‘Sustainable Development Goals’), adopted at the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015 and applicable in both developed and developing countries, requires States to ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ (Goal 11). Under Target 11.1 of Goal 11, States are expected to ‘ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing’. Ireland is a signatory to the 2030 Agenda; indeed, this country was joint facilitator (with Kenya) of the final intergovernmental negotiation of the Sustainable Development Goals.27

Despite this, Rebuilding Ireland makes no reference to Target 11.1 of the Goals and the promise which Ireland has made to ensure ‘adequate, safe and affordable housing’ for all by 2030. The UN Special Rapporteur on the right to housing, Leilani Farha, has pointed out that, at a minimum, Target 11.1 implies a commitment to end homelessness by that year.28 The Action Plan, however, does not even raise the question of setting a target date for ending homelessness.

Commodification and Financialisation of Housing

Absent from Rebuilding Ireland is any acknowledgment that commodification and financialisation of housing have been highly influential in the changes that have been brought about in the Irish housing system over the past two decades and are key factors underlying the serious housing problems now affecting so many households.

Commodification and financialisation mean that housing is seen not in terms of what should be its essential purpose – the provision of homes and the meeting of a basic human need – but primarily as a commodity, an asset, a means of speculative wealth creation, another element of the financial system which can be used to generate profits.

The process of commodification and financialisation of housing is a global phenomenon; it reflects core policies of neo-liberalism, including financial deregulation and trade and investment agreements which prioritise the interests of corporations, as well as the adoption by governments of policies through which it can be actively facilitated, including taxation measures and housing policies which reduce the role of publicly provided housing.29

The UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing has described the amount of private capital now being invested in housing and real estate markets worldwide as ‘staggering’.30 She has argued that the scale and impact of financialisation has ‘transformed’ housing,31 robbing it of its ‘function as a social good’32 and of its ‘connection to community, dignity and the idea of a home’.33

Others suggest we have now reached a point of ‘hyper-commodification’ of housing;34 they have summed up the outcome of this by describing one particular investment property in New York as being ‘not high-rise housing so much as global wealth congealed in tower form’.35

Policies which promote the commodification and financialisation of housing lead to increases in house prices and rents, an inadequate supply of social housing, and an increase in homelessness. In parallel with these trends, ‘speculative’ or ‘investment’ housing may be left empty on the basis that it will increase in value whether it is occupied or not. Another, and inevitable, outcome of housing financialisation is that, while growing numbers of people, including those on middle incomes, experience housing insecurity and unaffordability, the additional income and wealth now generated from housing flows upwards to the wealthiest. The result is not just greater inequality but the likelihood of increasing influence by such wealth-holders on policy, and the undermining of ‘democratic governance and community accountability’ in regard to housing.36

Commodification and financialisation obviously pose a serious threat to the realisation of the right to housing for every person. Indeed, the UN Special Rapporteur has described financialisation as ‘one of the greatest challenges facing the right to housing to date’.37 She has also highlighted that it is a major obstacle to the attainment of Target 11.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals.38

The Irish Housing System

An analysis of housing in Ireland published in 2005 showed how the housing policies then being pursued displayed the ‘predominant influence of a commodified philosophy of housing’.39 This was evident in the light-touch regulation of lending for housing and the rise in house prices; the promotion of the for-profit rental sector through tax breaks; the use of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) for the regeneration of local authority estates; the failure to provide a sufficient supply of new social housing.

It might have been expected that the financial crash, with its deeply damaging consequences for the housing system, the wider economy, and society as a whole, would have led to a turning away from policies of commodification and financialisation of housing in Ireland. Instead, these policies intensified. The austerity measures adopted to deal with the crisis included drastic cuts in funding for new social housing construction so that output fell to a fraction of what had been provided prior to the crash – which itself had been inadequate to meet social housing need. As a consequence of this lack of output, there was increased reliance on the private rented sector to meet the growing need for social housing.

Even more significant were the additional dimensions to the financialisation of Irish housing introduced through government policies in the post-2008 period. The priority given to restoring the banking sector meant that billions of euro worth of non-performing loans and distressed assets which had been taken over by NAMA and the Irish Banking Resolution Corporation (IBRC) were sold to international private equity firms at a considerable discount.40

The involvement of such funds in Ireland was facilitated by the approach adopted by NAMA and IBRC and incentivised both through existing tax exemption mechanisms and new tax measures introduced specifically for this purpose – for instance, in 2013, an exemption from corporation taxation was introduced for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs).41

In addition, Budget 2012 and Budget 2013 provided for an exemption from Capital Gains Tax for properties bought between 7 December 2011 and the end of December 2014 and held for at least seven years. This was an obvious additional attraction for multinational ‘vulture funds’ seeking to purchase distressed loans.

In a telling example of how financialised housing interests may seek to shape policy, both Irish and multinational firms put pressure on the Government in late 2014 to dilute the rent regulation proposals being proposed by the then Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government.42

A Government housing policy statement in 2011 at least showed awareness of the undesirability of commodifying housing: it declared that the policy approach being proposed ‘will neither force nor entice people through fiscal or other stimuli to treat housing as a commodity and a means of wealth creation’.43 In reality, of course, this declaration had no real influence on policy.

Rebuilding Ireland, however, does not even seem to recognise the potential harm arising from the commodification and financialisation of housing: instead, many of the policy approaches and measures proposed will inevitably continue and accelerate that process.

These include:

- the failure to make a commitment to provide local authority and voluntary sector housing on a scale sufficient to meet the need for social housing;

- the continuation and expansion of a privatised response to social housing need, through the extended use of rent subsidisation in the private rented sector (despite the rising cost of rents and the insecurity of the sector);

- the reliance on acquisitions and leasing from the private market to supply a significant share of the proposed increase in social housing;

- the proposals to deploy funding mechanisms involving various forms of private finance for the construction of new social housing, instead of funding this directly from public capital expenditure;

- the proposal that the use of private finance for the construction of new housing by voluntary housing bodies will be ‘intensified’;

- the expansion of the private rented sector without the far-reaching reforms necessary to make this an affordable and secure long-term housing option;

- the selling-off at below market prices of public land for housing development, on the basis that such development will include social housing – but, in fact, this will constitute only 30 per cent of the new provision;

- the failure to put forward proposals for an effective response to the hoarding of development land and of vacant sites in urban areas, which impedes the much-needed increase in the supply of housing.

- the unquestioning attitude towards the role of institutional investors, including global entities, in Irish housing and the apparent determination that Ireland will continue to be seen as an attractive destination for international investors in housing.

In summary, the approach proposed in Rebuilding Ireland suggests there is little prospect that ‘the march towards financialisation of housing’44 (toemploy a phrase used by the UN Special Rapporteur on housing) will soon falter, let alone halt, in Ireland.

Continuing the ‘Realignment’ of the Tenure Structure of Irish Housing

One of the most significant outcomes of the overall approach proposed by Rebuilding Ireland is likely to be the consolidation and even acceleration of the ‘realignment’ of the tenure structure of Irish housing which has been occurring for more than two decades.

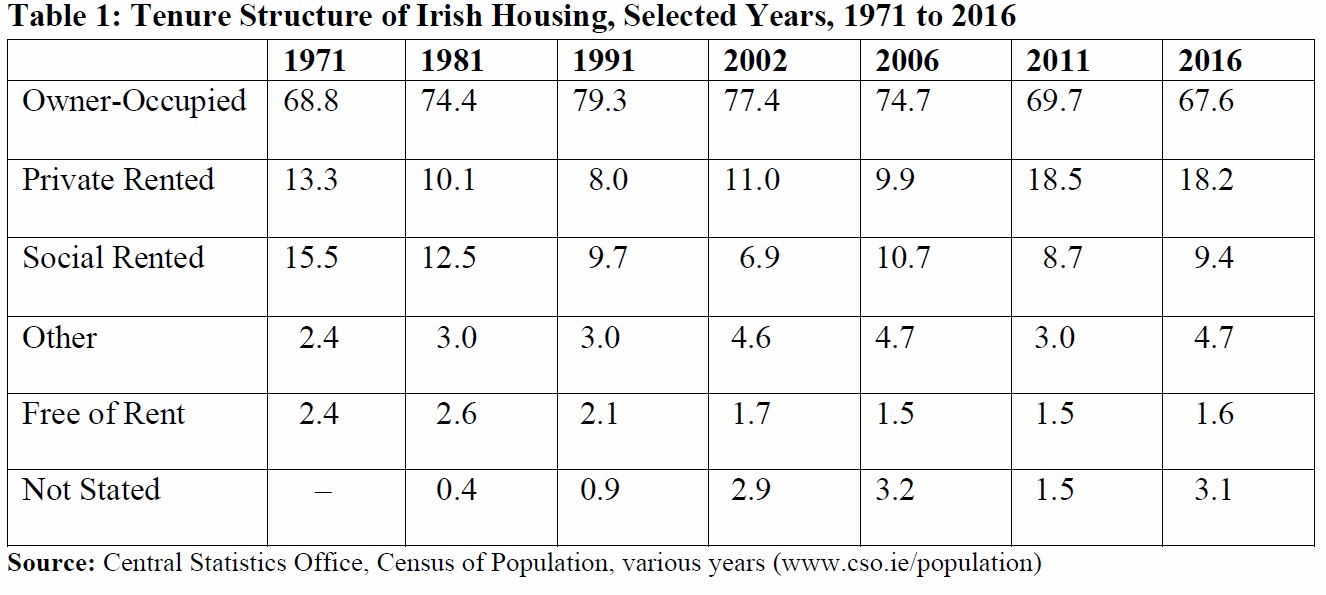

As Table 1 shows, changes in tenure have resulted in a marked decline in the share of housing that is owner-occupied: this fell from a peak of almost 80 per cent in 1991 to 69.7 per cent in 2011 and then to 67.6 per cent in 2016. The rate of home-ownership in Ireland is now lower than in 1971. In urban areas, owner-occupation was down to 59.2 per cent in 2016.45 At the same time, there has been a significant reduction in the percentage of households living in social housing – from 15.5 per cent in 1971 to 9.4 per cent in 2016.

The decline in relative terms of these two tenures has meant an increase in the share of housing that is private rented: whereas this sector represented just 8.0 per cent of all tenures in 1991, by 2016 it had risen to 18.2 per cent.

While the Action Plan acknowledges the decline in home-ownership, it downplays the extent of this, declaring that Ireland ‘still has one of the highest rates of owner-occupation in the OECD’.46 It overlooks a much more obvious point of comparison – the rate of home-ownership in the EU. Had this alternative comparison been used, it would have shown that the ownership rate in

Ireland (at 67.6 per cent) is now below the EU average (69.4 per cent), with this country’s fall in ownership since 2007 being significantly greater in percentage terms than that of any other EU Member State except the UK.47 In fact, only five of the current 28 EU Member States have a home-ownership rate that is lower than Ireland’s, the UK being one of these.48

A Change for the Better?

In keeping with the Action Plan’s ‘policy-free narrative’ concerning Irish housing development, the document provides no analysis as to how the reshaping of the tenure structure of Irish housing came about or what might be its implications for households and society in general.

The overall tenor of Rebuilding Ireland is one which implies approval for the changes that have occurred in the tenure structure. Thus, in the Strategy for the Rental Sector the falling rate of home-ownership is described as the country moving ‘towards international norms’49 (without specifying which norms are being invoked), and the assumption is made that the rate will continue to decline.50

Likewise, the policy of meeting social housing need through the use of rent supplementation in the private rental sector is presented as a positive development. The Action Plan claims that this policy has delivered ‘a better mix between private and social housing, rather than the reliance on large mono-tenure public housing projects which characterised housing investment in the 1960s and 1970s, many of which have since had to be regenerated in more recent years’.51

This ignores the obvious point that it is possible to directly provide social housing without developing ‘large mono-tenure’ housing schemes, and that there are many different ways of achieving the highly desirable objective of greater social integration in housing provision. It also ignores the serious disadvantages of using the private rental sector to meet social housing requirements – in the first instance for the households concerned; then for the State, in terms of the commitment to ongoing and growing expenditure, without ever acquiring a public asset in return; and then in terms of the distributional implications of the transfer of significant amounts of public money to private sector landlords (over the seventeen-year period 2000 to 2016, almost €6.1 billion was spent on Rent Supplement alone52).

Alongside the Plan’s benign view of the decline in both home-ownership and directly-provided social housing is a favourable perception of the growth that has occurred in the private rented sector. The document generally represents the increase in the number of households living in this tenure, including on a long-term basis, as if it were their preferred option, rather than, as is the case for many people, a situation imposed by insurmountable barriers to home-ownership or the unavailability of social housing.

The private rental sector is described in the Strategy for the Rental Sector as ‘a key building block for a modern economy’53 and the argument is made that the sector is an appropriate option for ‘a mobile labour market’,54 without any analysis of what share of the labour market is characterised by a high degree of physical mobility, and without reference to the reality that once households have children the feasibility of moving location greatly diminishes.

Rebuilding Ireland even describes having a larger private rental sector as insulation against ‘the macro-economic risks of an over-reliance on home ownership’ – with it, apparently, helping to prevent booms in this sector.55 There is no acknowledgment that a sovereign state with the will to do so should have mechanisms available to it to curb unsustainable rises in houses prices. Neither is it acknowledged that unsustainable booms might also occur in the buy-to-let sector.

Furthermore, it is argued that the expansion of the private rental sector is critical to this country developing ‘a truly affordable, stable and sustainable housing sector’.56 Under Rebuilding Ireland, the potential of no other tenure type – be it of home-ownership, co-operative housing, local authority, voluntary housing provision, or any new form of public housing – to meet Ireland’s growing housing needs, and to ensure the desired ‘affordable, stable and sustainable’ housing system, is accorded this level of significance.

Yet despite all the arguments uncritically presented in favour of increasing the role of the private rented sector, the Action Plan still finds it necessary to declare that a ‘key housing challenge’ for Ireland is that of ‘changing attitudes such that the advantages of rental as a form of tenure are more widely recognised’.57 Similarly, the Strategy for the Rental Sector refers to the necessity of ‘changing cultures’.58 It has to be asked: if the advantages of the private rental sector are as evident as Rebuilding Ireland repeatedly asserts, why is there need to engage in such deliberate reshaping of public opinion?

May Day March, Dublin, 2017 © DSpeirs

Perhaps the answer is simply that in the face of some of the realities of the sector – increasing rents, which have now reached record levels, the still-limited security of tenure for private renters, and the poor standards of accommodation found in many parts of the sector – it is indeed considered necessary to contrive to somehow change perceptions, if only by repeating the same message in the hope that it will eventually be accepted, however little it may accord with reality.

Implications of the Change in Tenure Structure

Rebuilding Ireland does not explore the far-reaching consequences of the threefold change represented by a continued fall in the rate of home-ownership, a reduced role, in relative terms, for social housing provided directly by local authorities and voluntary bodies, and an increased reliance on the private rented sector.

These changes in tenure will, in the first place, have important implications in terms of housing security for an increasing number of households. Many of those destined to live for a prolonged period in the private rented sector will do so against a background of continuing insecurity, given the absence of any firm proposals that would provide for lengthy leases or ensure rent affordability in the long-term – since the reality is that whatever other provisions for security of tenure may be put in place a tenant’s right to remain in their rented accommodation will, in the end, come down to their ability to pay the rent that can be legally demanded.

Meanwhile, the reliance on the private sector to meet social housing need will leave growing numbers of low-income households without the prospect of any long-term security in their housing situation – and indeed, in many instances, with very little security in the short-term.

A key feature of the ‘modern economy’, not acknowledged in Rebuilding Ireland, is that large numbers of workers, particularly in the younger age-groups, now experience precarious and low-paid employment, as a result of, for example, the casualisation of previously secure employment sectors, the emergence of bogus self-employment, the lack of options other than part-time and poorly-paid work.59 It may well be asked: in what ways is an expensive and largely insecure private rented sector an appropriate housing response for such workers? Is it right that those who are the victims of precarious employment should also be forced to endure precarious housing conditions?

Rebuilding Ireland promised support for the development of ‘an affordable rental programme’ to help meet the housing needs of middle income groups and the later Strategy for the Rental Sector refers to a commitment to develop a ‘cost rental’ model. However, there is no indication that what is envisaged is provision of ‘affordable rental’ on such a scale that it would offer a real alternative for the large numbers of households now in the private rented sector who have to spend a disproportionate share of their income on rent and who have no long-term security.

Older people

The Action Plan refers to the housing challenges arising from an increase in the proportion of older people in the population, and notes that it is Government policy ‘to support older people to live with dignity and independence in their own homes and communities for as long as possible’.60 It notes also the ‘specific housing requirements’ of older people, such as ‘being in proximity to their family and social networks and the need for access to public and other essential services’.61

However, the statement of such laudable principles is not accompanied by any acknowledgment, let alone discussion, of the potential consequences for people in older age of a decline in home-ownership and a fall in directly-provided social housing, with a resulting increased reliance on the private rented sector. It is as if the specific section on housing for older people was written without taking account of the implications of the tenure structure that will inevitably follow from the core proposals in Rebuilding Ireland.

The Plan does not, for example, look at the question of how those living on considerably reduced incomes in retirement are to meet the cost of renting in the private sector62 – or advert to the deepening sense of anxiety and dread about their housing situation which private sector renters are likely to experience as they become older. A retirement income that may be one-third or even one-quarter of that received while in employment will simply not be sufficient to meet the cost of renting in the private sector. And a lifetime of expensive private renting is likely to leave very little scope to build up substantial savings or pension funds for use as rent in old age. Indeed, the envisaged future of increased long-term private sector renting needs to be viewed against the background of the reality of low rates of occupational pension cover among private sector workers.63

It might be noted that the 2016 assessment of social housing need showed that the number of households where the main applicant was over 60 years of age rose from 4,765 in 2013 to 6,594 in 2016 (an increase of 38 per cent).64 Given that Rebuilding Ireland proposes a more limited role, in relative terms, for social housing directly provided by local authorities and voluntary bodies, will these sectors be in a position to provide for retired people who will be forced to leave their private rented housing because it is no longer affordable? Or will the only option for such people be to re-locate to cheaper private sector accommodation and rely on schemes such as HAP, whose attendant insecurity is likely to bear all the more severely on people at a stage in life when they may face many other difficulties, such as the loss of a partner, illness or disability?

Neither does the Action Plan consider that a policy of increased reliance on the private rented sector may have important implications for meeting the costs of long-term home or residential care for older people. What might be the future of a scheme, such as Fair Deal, where part of the value of an older person’s home can be taken into account in the arrangements to meet the costs of nursing home care?

Intergenerational and social equity

The change in the tenure structure of Irish housing already occurring, and likely to be accelerated by the Action Plan’s proposals, has both inter-generational and social class implications, but these are not considered in the document.

Analysis carried out by the National Economic and Social Council (NESC) of census data over the period 1991 to 2011 revealed that during these two decades the percentage of heads of households in the age category 25–34 who were owner-occupiers declined significantly (falling from 68.4 per cent in 1991 to just over 40 per cent in 2011). There was a smaller but still notable fall in ownership in the 35–44 age group (from 82.2 per cent in 1991 to 68 per cent in 2011).65 The 2016 Census shows a continuation of this downward trend: the ownership rate for households in the 25–34 age group was down to 30 per cent in 2016 (less than half the rate in 1991) and for the 35–44 age group it was down to 61 per cent.66 With the decline in home-ownership for these groups has come an increase in the proportion renting in the private sector.67

Particularly noteworthy is the growing difference in ownership rates between households headed by a person in the 35–44 age category and those headed by a person aged 65 or over. In 1991, ownership rates were almost the same for the two groups (82.1 and 82.2 per cent respectively). By 2002, there was a drop in the ownership rate of the younger group, but not of the older.68 Each census since then has shown a continued widening of the gap between the two groups, with the 2016 census revealing a 25 percentage point difference: the ownership rate for the 35–44 age group was by then 61 per cent, as against 86.5 per cent for the ‘65 and over’ category. If present trends were to continue then clearly we are looking towards a future where from among ‘each successive cohort of young people’69 fewer and fewer will be able to own a home.

A key feature of the decline in home-ownership is the social class nature of this. Again, this question is not adverted to in Rebuilding Ireland. At the peak of owner-occupancy in Ireland, while there were variations in the rate of ownership between socio-economic groups, there was still quite a high rate of ownership among skilled manual, semi-skilled and unskilled workers (a major factor contributing to this being the various schemes over the years to enable local authority tenants switch to owning rather than renting their homes). As the rate of ownership for the country as a whole declined, this began to change. The analysis by NESC showed that, within the overall reduction that occurred between 1991 and 2011 in the proportion of households in the 35–44 age group which were owner-occupiers, the percentage decline was more severe for those in the classes termed ‘skilled’ (down 13.5 per cent); ‘semi-skilled’ (down 13.3 per cent); ‘unskilled’ (down 15.9 per cent) and ‘all other gainfully occupied’ (down 20 per cent).70

The 2016 Census revealed a drop of 47,000 in the number of households with mortgages as compared to 2011,71 and it is reasonable to assume that the social class differential in ownership trends identified by NESC for the period 1991 to 2011 will have persisted between 2011 and 2016. Should this trend continue the implication is clear: in the future, only the upper-middle and high income groups, and those who can rely on inheritance or assistance from family, will be able to aspire to home-ownership.

The change in tenure structure will have important consequences in terms of wealth distribution. Data on wealth-holding in Ireland show, firstly, that there is gross inequality in the distribution of wealth (in 2013, the richest 10 per cent owned 53.8 per cent of wealth, and the top one per cent owned 14.8 per cent), and, secondly, that for households outside the richest groups it is the family home which constitutes most, if not nearly all, of any wealth they own.72

A fall in home-ownership means, in effect, that the housing system will serve to consolidate and increase inequality in wealth distribution. At one extreme, a growing number of households will have little wealth – or none at all, and at the other extreme, among the wealthiest groups, ownership of housing other than their own dwelling-place will increasingly represent a source of wealth73 (and probably of income).

Conclusion

Far from being the policy-free phenomenon implied by Rebuilding Ireland, the transformation of the housing system in Ireland over the past quarter of a century starkly reflects particular policy choices made by successive governments. These choices have meant that Irish housing in this period has been shaped far more by international trends towards the commodification and financialisation of housing (and, by implication, neo-liberalism) than by a concern to give effect to the right to housing, even though Ireland has committed to implementing this right through its ratification of international human rights treaties.

At issue here is not some academic debate about a preferred model of housing development but the question: what has been the result of such policies? It is clear that in a variety of ways, the result has been to plunge an increasing number of households into a situation where their housing is unaffordable, or insecure, or grossly inadequate – and in many instances all three.

For a great number of individuals and families in Ireland, housing has become a source of financial hardship, of constant worry, stress and fear for the future. Those most severely affected are, of course, people who are homeless, but many others are experiencing the impact of the crisis, including those who are in danger of losing their home because of mortgage default; those paying such a high proportion of their income on rent that they cannot afford other essentials; those forced into involuntarily sharing a home with friends or family and who endure the associated overcrowding and inconvenience; those living in grossly inadequate conditions but compelled to wait years on social housing waiting lists.

Housing has always been characterised by inequality, but during the first seven decades of the existence of the Irish State significant progress was made towards widening access to good quality housing in both urban and rural areas, and in reducing inequalities within the housing system. In more recent times, however, housing has become the locus of some of the deepest inequality evident in Irish society. This is apparent not just within the housing system itself (in terms of housing conditions, affordability and security) but in the ways the housing system is serving to redistribute income and wealth in a regressive manner.

While Rebuilding Ireland sets out a range of specific measures in response to aspects of the current housing crisis, it fails to address questions that are of fundamental importance if Ireland is to develop the ‘affordable, stable and sustainable’ housing system of which it speaks. This is evident in the fact that the Plan ignores the issue of the right to housing and fails to recognise and respond to the threat posed by the global phenomenon of financialisation of housing.

Essentially, the Plan reflects a determination to continue the market-dominated approaches to housing which have prevailed in Ireland for over a quarter of a century with such harmful outcomes for both individuals and the common good.

The claim that ‘the market’ will resolve Ireland’s housing problems has been the standard argument for far too long. There is little evidence to support this contention. In 2006, for example, over 88,200 houses were built all over Ireland by the private sector but in many areas where they were built they were simply not required. This ‘market failure’ and miscalculation, influenced by ‘light touch’ regulation, contributed to the crash in 2007 and the consequent suffering for so many since then.

In recent years, the market has again consistently failed to respond. In 2016, despite high demand (it has been estimated that long-run demand for housing in Ireland is in the region of 30,000 to 35,000 new units per annum74),desperate need and escalating house prices, output of new housing in the private sector was significantly below this level. (Precisely how far below is unclear. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government figures indicate that 14,354 homes were built by the private sector in 2016;75 the Economic and Social Research Institute suggests that the number is just over 12,000;76 Davy Research has suggested that the figure is ‘closer to 7,500’.77) In any case, it is clear that the regular exhortation to ‘increase supply’ has been ineffective. When markets fail in this way, governments must play a far more active role in both the construction of homes and ensuring that house prices and rents are affordable.