This is the second blog in a three-part series by Niall Leahy SJ entitled “Who are the Localists?” Localism is both a reality and a countervailing idea challenging the globalist extractivist paradigm and its adherents.

My last post focused on localism as practiced by small farmers, but localism is as much an urban phenomenon as a rural one. Towns and cities all over the world are putting localist development principles into practice. In some circles, they call it Doughnut Economics.

The Doughnut

Economist Kate Raworth believes that sustainable economies are like doughnuts. The outer ring of a doughnut-shaped economy represents the ecological ceiling or limits that it cannot go beyond without damaging the environment it depends on. The inner ring of the doughnut represents a social foundation—the basics that people need to live, like food, accommodation and healthcare. If economies operate within the circle of dough, communities and the environment will both flourish.

While the Doughnut Economics movement doesn’t promote itself under the label of localism; localist and community-based development principles are evident in their approach. Urban circularity is an important strategy for staying within the doughnut. That can mean the establishment of local food systems, the generation of energy locally, and the support of small and micro-businesses. The decision-making process also requires input and participation of local stakeholders. In the language of Catholic Social Teaching, the Doughnut model champions both economic and political subsidiarity. More on that in my next post.

The most obvious difference between doughnut economies and modern economies is the voluntary acceptance of a limit to production and consumption. Consumer capitalist economies are built on, and actually depend on, the idea that growth and expansion is always good. Raworth does not believe that dependency on economic growth ought to be baked into the system. Nor is she against growth. She holds that depending on the situation, growth may or may not help a given economy to operate within the doughnut.

A journey across space and time

Raworth had to go on a life-journey herself to get from the classical growth-based economics she learned at Oxford University, to the deceptively simple doughnut model. She spent time working in Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania, where she saw tourism wreaking havoc with the local ecosystem. From there she moved to New York to work on the UN’s annual Human Development Index report that ranks nations’ prosperity according to quality of life, rather than GDP. More seeds were sown there. In 2009 she was working as a researcher for Oxfam, and it was here that she had her Eureka moment. She came across the Stockholm Resilience Centre’s report on how global economic activity was outstripping the earth’s capacity to support it. This was the starting point for her economics for the 21st century.

The subtitle of her book Doughnut Economics which reads “Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist” alludes to a journey that not only took Raworth across continents, but across centuries. She began to see that the foundational ideas of modern-day economics are 19th century ideas that have aged badly. She writes, “[c]itizens of 2050 are being taught an economic mindset that is rooted in the textbooks of 1950, which in turn are rooted in the theories of 1850.” Her project is to situate economics in the reality of planet Earth today, rather than in the failed dreams of the past.

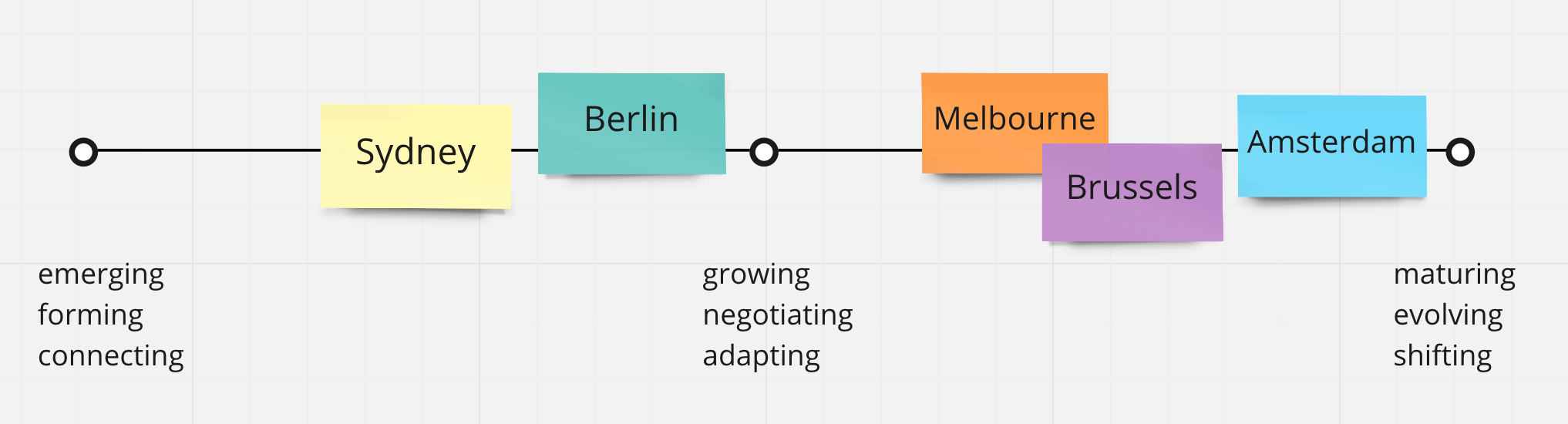

To this end, in 2017 Raworth launched DEAL—the Doughnut Economy Action Lab—which provides a suite of online tools and stories to empower communities to start “doughnutting” their economies. Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Melbourne and Sydney are all engaged in the process, albeit at different stages. Amsterdam was an earlier adopter. They are setting the pace and are an inspiration to other major urban centres across the world.

Politics for the 21st Century

From the many doughnut initiatives that are taking place, it is becoming apparent that real and sustainable transformation is more likely when there is buy in from community volunteers and the local urban authorities and civil servants. This willingness to generate ideas and build from below and support from above is a style of urban governance that transforms struggling urban communities into prosperous and convivial spaces. Raworth has not just developed an economics for the 21st century, but a politics too.

If you would like to know more about Doughnut Economics in Ireland, you may wish to contact Lara Kelly at who works for the Congregation Justice Office of the Dominican Sisters, Cabra, Dublin. Her email address is [email protected].

Links and resources

A fifteen minute TED Talk by Kate Raworth