Naming the Assumptions

Let us start by stating two common assumptions:

- Religion is something that is attractive to people who are, for whatever reason, unable to deal with harsh reality.

- Organised religion is an outmoded institution, a holdover from an unmissed past.

The first position used to be extended often by Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens and their ilk. I have heard it myself: that religion is a sort of psychological crutch for people who can’t quite cope.

While it seems like it might have some substance when you first hear it, this always struck me as a very vague critique. For one thing, crutches are good things! If you can’t walk yourself, better to have a device to assist you. Without wanting to dilute the important concept, there is an ableist arrogance hidden in this objection.

But more fundamentally, this critique only works if you disregard the details. As a rich and educated man from the West, the Christian good news is not immediately that good for me. Jesus is very clear that I am in a spot of bother. Sitting on top of centuries of imperial conquest, rapacious capitalism, and cultural superiority, parables like Lazarus and the Rich Man do not naturally assuage any anxiety I may suffer.

The second assumption may be even more widely held. It runs in the background when people declare they are “spiritual, not religious”. It is not hard to understand this impulse, especially when you consider the horrendous corruption that has been found in churches over the last fifty years.

But it is getting harder to ignore how, for all their compromise and frailty, there is a particular potency in religion being organised. If we take the on-going example of Christian opposition to the harsh anti-immigration regime being enacted in the USA, they are at the vanguard. And from the very top of the hierarchy to the grassroot protests, it is hard to imagine this kind of resistance if there wasn’t ecclesial structures in place to form people who are attentive to the ethical issues and call people to the frontlines.

Concrete Realities

Whatever generalised concerns we might have about these assumptions, in the last week we have had very concrete reasons to dispute them. Although not widely reported, in a conversation with the billionaire tech leader John Collison, the Taoiseach seemed to admit that he no longer sees environmental adaptation as a government priority. “I don’t think we can mitigate for climate change,” he confessed.

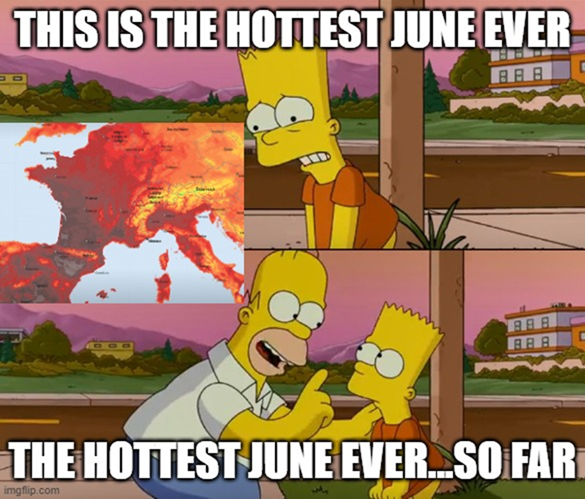

This is devastating news. In the last few weeks we have heard about the thousands of Europeans who have died this summer as a result of climate collapse, the very real impact extreme weather is having on our economies, and that we have gone past the point of no-return on saving one of the ocean’s most important eco-systems. Climate collapse and biodiversity breakdown are not problems for the future. They are already hitting us hard now and that impact will only get harder.

We must be clear here and underline that Micheál Martin has not in any way embraced climate denialism. In his own comments he was eager to communicate that he sees the crisis for what it is. But it seems that from his perspective, there is no popular mandate for a concerted effort to improve our environmental health. He worries that such moves would “divide society fairly fast and we’ll then get a negative reaction against good, progressive policies that seek to address climate and very serious issues.”

Positive Possibilities

While it is common to imagine that religion is the recourse of those who can’t face reality and that churches are outmoded institutions, here we see those problems fully on display in contemporary politics. Put very bluntly: climate change does not care about opinion polls. It is a physical reality that the surplus carbon dioxide in our atmosphere will accelerate the already dramatic changes in our climate. Delaying responding to that is like thinking you can jump out of an airplane and somehow assemble a parachute as you fall. Gravity will not negotiate with your electoral timelines; neither will mass extinction.

But while our political leaders shirk from reality and the institutions they govern stumble and stutter towards change, a different response is on display from religious leaders. As Micheál Martin was making his comments, the Pope had gathered leaders – young and old – from across the world to Castel Gandolfo for an event entitled Raising Hope. (Many, of course, made the effort to travel slow – like my colleague Fr Niall Leahy!) It is not like religious leaders do not have to deal with scepticism among their communities. But the truth demands a response. Drawing together figures as diverse as the evangelical climate scientist Katherine Heyhoe and the former Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Pope insisted that the nature of the crisis required both personal transformation and dramatic policy shifts.

The location of the event was significant. This is the place where the Popes escape the increasingly dire heat of the high Roman summers. And it is also being set aside as a hub for environmental education, advocacy, and experimentation. Recognising that the environmental crisis is also a crisis of fossil capitalism, the Vatican is gathering young economists, social enterprise leaders, and entrepreneurs from around the world in an attempt to imagine alternative pathways. And these institutional moves are not just coming from the top. There are few environmental commitments in Ireland as ambitious as the Irish bishops’ plan to set aside 30% of their land for biodiversity health by 2030.

A Way Forward

Religious communities are not perfect. They have their own (catastrophic) failures. But at their best, they remind us that conviction need not mean rigidity and that tradition can be a reservoir for renewal. Contrary to common assumptions, when faith is lived honestly, it trains people to face the hardest truths about the world and themselves – sin, suffering, death – without despair. That is why they can also face the reality of climate collapse and biodiversity breakdown without denial.

Leadership sometimes means taking the positions that might not be popular, but are right. In this sense, the churches may have something to teach. When it comes to environmental care, they are imperfect institutions that nonetheless know their story, draw on their sources, and commit to (try to) act with integrity. Politics, too, can learn to believe in something again: the common good. The climate crisis is not waiting for consensus. It cannot be evaded through cynicism. We need leadership that sees clearly, speaks plainly, and acts decisively. And perhaps, in that work, the political and religious are not so far apart. Both must find the courage to hope.