Micheal J. Kelly SJ is an Irish Jesuit missionary who has spent his life in Zambia, who is respected globally as a speaker and campaigner who works to combat HIV/AIDS in Africa and beyond. In this piece, he applies his years of learning and experience to predict the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the poorest countries in the world.

“Less than five months after the first recorded case of what has come to be known as Covid-19, there have been almost 2.5 million confirmed infections and 160,000 deaths across 185 different countries, which have taken unprecedented measures to prevent its spread. At the same time, public health experts acknowledge that the volume of infections, especially in parts of the developing world, may be far greater than official figures.

In response to the escalating spread of the disease, many countries have adopted lockdown measures and emergency response procedures that prohibit people from entering or leaving designated areas. In some form or other these are now almost universal. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), “Full or partial lockdown measures are now affecting almost 2.7 billion workers, representing around 81 per cent of the world’s workforce”.

As recently as January 2020 the forecast from the IMF had been that global GDP would expand by 3.3% during the current year. In contrast, the Fund stated in mid-April that not only would the global economy not expand, but that as governments worldwide grapple with the global Covid-19 pandemic, the worldwide economy could be expected to contract by 3% in 2020. The “Great Lockdown” appears to have ushered the world into its most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The IMF’s chief economist has warned that “[w]hen you have a deep recession of this kind, there is always unfortunately tremendous loss of income for people at the lower end of the income scale, so poverty can go up, inequality can go up”.

The Impact on Poor Countries

This spectre of an increase in poverty and inequality constitutes a real challenge for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of ending poverty and eliminating hunger by the year 2030. The economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic are generating whole new levels of poverty, bringing the world back to where it was many years ago and wiping out decades of progress. Estimates by the United Nations University (UNU), the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) suggest that globally, the numbers living in poverty are set to increase for the first time in the last thirty years and that the increases will be substantial.

One measure of poverty is the international poverty line; the income that a person needs in order to satisfy his or her minimum nutritional, clothing and shelter needs. In October 2015, the World Bank set this standard at $1.90 per day. Anybody living on less than this is considered to be living in extreme poverty.

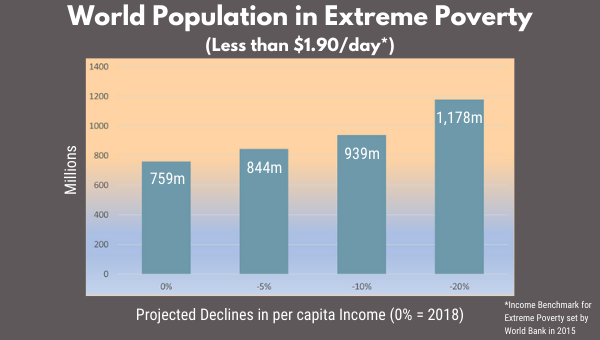

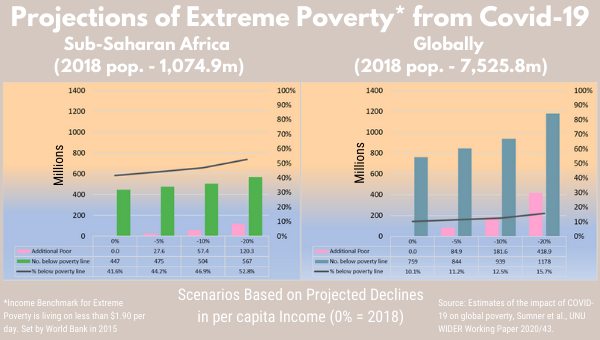

It has been estimated that in 2018 just over 10% of the world’s population or 759 million people were living in such extreme poverty. According to UNU projections, a Covid-19 induced decline of 5% in per capita incomes or consumption would result in an increase of 85 million in the number living in poverty. If the decline reached 10%, the number living in poverty would increase by more than 180 million; while a decline of 20% (which seems to be the most likely scenario), would result in there being an additional 419 million extremely poor people in the world. This means that across the world there would be a total of 1,178 million extremely poor people – 15.7% of the world’s total population – something almost unprecedented in world history.

The Impact on Sub-Saharan Africa

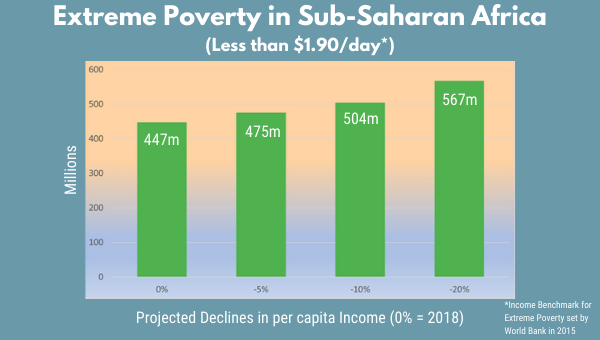

The prospects for Sub-Saharan Africa are equally grim. In 2018 this part of the world was home to an estimated 1,075 million people, of whom 447 million (41.6% of the total), were living below the internationally accepted poverty line of $1.90 a day.

A Covid-19 induced decline of 5% in per capita incomes or consumption would see this number increasing by almost 28 million to nearly 475 million, which would be 44.2% of the region’s population. A decline of 10% would see the increase grow to 57.4 million, while a global economic decline of 20% would result in Sub-Saharan Africa’s population of extremely poor people increasing by more than 120 million. In such a case the number of extremely poor people living in the sub-continent would be 567 million, or 52.8% of the total population of the region.

Instead of progressing out of poverty, Sub-Saharan Africa would see a reversal of decades of progress, becoming poorer than ever before.

It would share this calamitous state with South Asia, with the two regions accounting for some 80% of the total poverty in the world.

The figures that have been presented give the poverty situation of those living below the international poverty line of $1.90 a day. This is focusing on poverty in terms of the monetary indicator provided by a cash income. But there are other dimensions to poverty which will also be adversely affected by Covid-19 and the measures taken to prevent its spread. Thus, the Covid-19 pandemic-induced recession can be expected to lead to increases in infant and maternal mortality rates, to more fragile health systems, to an increasing incidence and depth of undernutrition and undernourishment, and to lower school attendance, progression, and completion rates. It also seems probable that declines in school participation and educational attainment would affect girls more than boys because once they have stopped schooling for any reason, girls are known to be less likely to be able to begin again when opportunities for resumption occur.

The Ongoing and New Poor

Who are these millions newly plunged into deep poverty by the tsunami-like impacts of Covid-19? They are the ones who belong to the untaxed and unregulated informal economy that is estimated to make up 55% of the economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. They are the thousands who have lost their jobs because of the virtual collapse of the tourist industry and the closure of hotels. They are the construction workers who, for fear of virus infection, are no longer permitted to work on building sites. They are those who belong to the small and medium enterprises that create 80% of the employment across Africa. They are the ones who, like the men in the Gospel parable of the Labourers in the Vineyard, are standing idle all the day because no one will hire them. They are the weak and marginalised members of society.

Social distancing norms that can be widely embraced in northern Europe are a different prospect in sub-Saharan Africa. Most people live in homes so small and crowded that the recommended social distancing is impossible. And even though the chance of securing some form of employment is very low, it is impossible if kept indoors. Street vendors can’t work from home!

Risk of Illness or Hunger

What can people do but take the risk of contracting (or spreading) the Covid-19 disease, rather than face the even greater risk of sickness from hunger and possibly starvation in their families. Even the relentless handwashing appeals take on different meanings when one must draw water from a common public water-tap, at most twice in the day – and no one has the money to even buy soap! Those who need to work to live are now on the precipice of working and still dying. They are the long-standing poor, the poor that the Gospel says will always be with us, the poor whose numbers are being increased every day by the Covid-19 pandemic as it throws millions more into poverty.

What Are We Doing to Help?

But way beyond all of this, they are God’s children. They are our sisters and brothers. Are we doing anything to help them? Or are all our Covid-19 pandemic concerns focused on ourselves and on manoeuvring ourselves successfully through this crisis?”

The Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice has joined with partner organisations around the world to call for a debt amnesty for developing nations. This would be one, small step towards help. Ireland, rightfully proud of the role it has played in global development, can take a lead in this necessary initiative to help counteract the human tragedy of Covid-19.