Integration in Action

With the rise of Far-Right violence, the question of social integration has become a key conversation. But if you want to see integration in action, the first place to go is not a political press conference or a strategic document. Go for a walk on a Sunday morning through Dublin’s north-east inner-city instead. You might hear Yoruba hymns floating out of a converted office block, incense drifting from a Romanian Orthodox service, and gospel choruses in Mandarin echoing from among a row of residential buildings. Step inside any of these communities and you will find the real architecture of integration – ordinary Dubliners mixing with those newly arrived to our shores, building community quietly and transformatively.

These gatherings are not in anyone’s regeneration plan. They do not feature in local authority plans or the glossy reports produced by the NEIC initiative. Yet they are essential to building the common good in the area. In these rooms, people hear about jobs, find flats, share food, mind each others’ children, teach each other English, and translate the paperwork that helps a new neighbour secure a footing in our society.

New Research

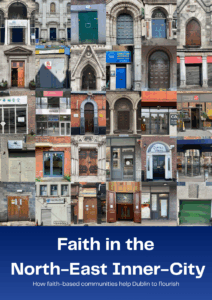

The Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice’s new report, Faith in the North-East Inner City, maps 49 different faith-based communities in that one small slice of Dublin alone. They range from mosques that gather in an easy-to-miss laneway, Pentecostal congregations meeting in school halls, to long-established parishes. Each of them does work that politicians often only want to talk about: helping people belong.

[Click image to download full report]

Executive Summary is available for download here

This is what we might call Dublin’s hidden social infrastructure. The thick web of faith communities represent a network of trust that helps our complex city function. We found that they were often the first port of call for people when they first arrive in Ireland. They are places where social bonds are established, but also where social bridges to the wider community can be accessed. The range of services we discovered – leaving aside anything spiritual in nature – was astonishing. They help with speaking English, navigating bureaucracy, finding employment, advancing in education, locating accommodation, and that essential assistance in making sense of the “way things are done here.” They run services for children, teenagers, those newly married, and those deep into retirement. They even make a difference in terms of providing pathways towards healthcare.

Policy Blindspot

And yet official Ireland barely acknowledges their existence. In the course of the research, it became clear that neither Dublin City Council nor the NEIC Initiative has any up-to-date record of where these communities meet, who leads them, or what work they do. The Public Sector Equality and Human Rights Duty requires local authorities to consider religion when designing services. But in practice, religion is treated as merely a private eccentricity, something best avoided for fear of controversy.

That blind spot costs us. When the riots erupted in this area in November 2023, Gardaí scrambled to reach the most vulnerable people who would be frightened for their safety. A recurring theme throughout our interviews is how much people appreciate the work of Gardaí Community Liaison Officers. But in many cases, it seems they did not know where to go, or whom to call, because no official channel existed. After the fact, when contact was made, co-operation was warm and immediate. The networks were there all along, but they are effectively invisible to official Ireland.

Faith communities are not looking for special treatment. They appreciate the freedoms that are secured by living in a secular Republic. But they do need to be seen. They have a valuable contribution to make on questions about housing, safety, and health access, and they are especially at risk of anti-migrant violence.

A Vibrant Pluralism

Ireland has changed, but it seems sometimes the State is slow to realise that means Irish religiosity has changed too. It is true that the north-east inner-city has undergone dramatic demographic change. But whatever stability that persists is in part maintained these “third places” (neither work nor home) where people meet in their diversity and find a community that lets them put down roots in this society.

If the State is serious about integration and about preventing the fear and misinformation that fuels Far Right agitation, it needs to stop bypassing religious expression. It should build channels of communication with local faith leaders, train public servants in religious literacy, and create liaison roles in councils to connect these networks with official structures. To take their contribution seriously is not to undermine secularism, but to allow it to catch up with the vibrant pluralism that already exists in our society.

In Ulysses, James Joyce muses that it would be difficult to chart a path across the city without passing a pub. It is now difficult to walk through the north-east inner-city without passing a faith community. But it is, nonetheless, easy to just pass them by. This is a mistake. These communities can be a cornerstone for an integration response that will renew Dublin’s social capital.