Christians today are not known for their sense of humour. But they must have been funny at some point. Calling their commemoration of the death of their Messiah ‘Good Friday’ testifies to that.

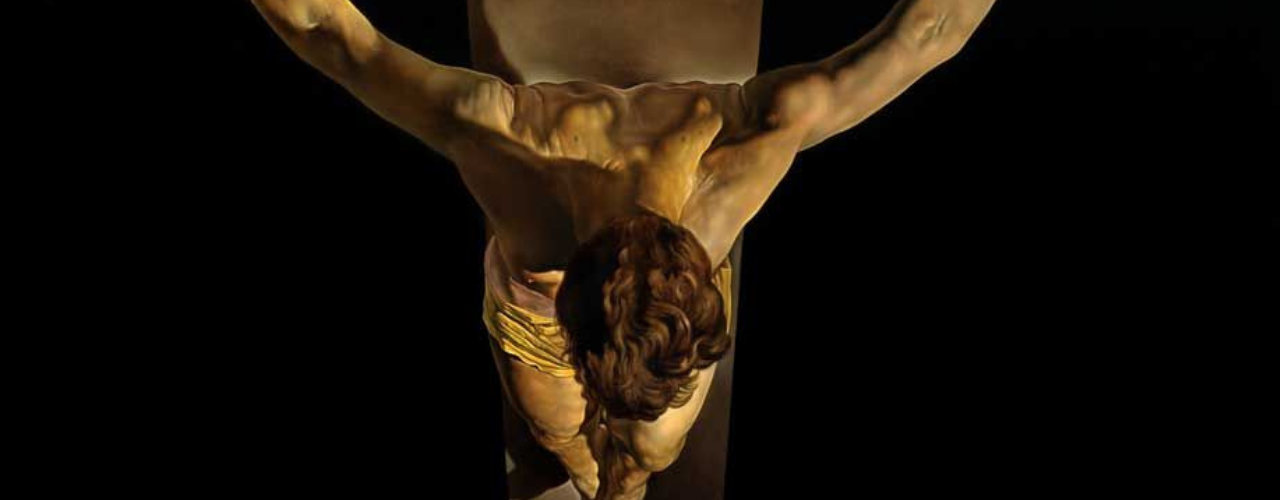

The Romans crucified thousands of people in the decades before and after Jesus of Nazareth. Since the son of Mary suffocated to death under the weight of his own body, many millions more have died at the hands of brutal, cowardly, corrupt tinpot mimics of Pontius Pilate.

Remembering this one single act of lethal state violence seems like another absurd gesture.

But that is the point isn’t it?

We live in an age largely deaf to the oddness of this strange story, exhausted by decades of droning sermons delivered within institutions who certainly did not act as if they were following after a God who identifies with the abused and abandoned. Seen from the underside of history, the day you find God is on your side is definitely a good day. And Jesus’ death is savagely excruciating, but it is not in itself remarkable. As Francis Spufford puts it

Jesus dies like a migrant worker who suffocates in a freight container, like a garbage-picker caught in a slide, like a child with an infected finger, like a beggar the bus reverses over. Or, of course, like all the other slaves ever punished by crucifixion, a fate so low, said Cicero, that no well-bred person should ever even mention it.

Good Friday is loaded with meaning. But right at the centre of that cross, where God’s perfect justice intersected with his perfect love, we must recognise that the meaning of existence is not to be found in the framing of history texts written to flatter the Caesars and CEOs and all their extraordinary achievements but is located in the unrecorded detail and texture of the daily failures of those forgotten by the world.

The early Christians could tell a good joke in part because they understood the cataclysmic consequences of the punchline of Easter. That God became a human is a remarkable claim, but Christianity goes further. It says God became an ordinary human, a guy that the powers-that-be would never notice, if only he’d been wise enough to keep his head down. Born in obscurity, without wealth or status, on the periphery of the periphery of the empire, he spent the years of his public ministry welcomed by the outcasts and the scandalous. He was the antithesis of the superhero; a tradesman who died with nothing but a few peasant women brave enough to identify with him. Those same early Christians concluded “what God becomes, God redeems” and they grasped that the joke there is on the rich, the powerful, the influential.

Christianity appears to be in terminal decline in the western world, where the hegemony of globalised neoliberal capitalism seems to be immune even to pandemics. It is, at the very same time, growing explosively – faster than at any time apart from the first century – everywhere else. Not just in the places you know of like Brazil and Uganda but in Iran and China too. Christians in Ireland continue to evade this fact, marshalling all sorts of explanations to avoid the obvious conclusion. But Easter is always a hill too steep to die on.

Those few women left around the cross were the followers who were so marginalised, it was debatable whether their culture saw them as human. The story spread across the known world so rapidly because it won the favour of slaves and women. Even the powerful who adopted it were in the margins. As it was then, so it is now: Jesus tends to be despised by those on top of the world and welcomed by those crushed underfoot.

Good Friday is ultimately good because it is not the end of the story. Sunday is coming. The revolution is more total than anything imagined by the secular utopias that ravaged the last century. It is the complete reversal of the story that the successful like to cherish like a sacred tale: the last shall be first and the first shall be last.

So Happy Easter. The attempts to domesticate this strange tale remain delightfully absurd – bunnies bearing chocolate eggs and buns with sugared crosses – but the meaning remains transformative: God has personal experience of just how bad humanity can be and God loves us still; all of us. This is not meant to be the material for private piety but public rebellion against the complacency which quietly hints that injustice is the way things are meant to be.

Let us remember the history recorded with surprising accuracy by the four Gospels and side with those who stuck around, mimic those who did not despair, and associate ourselves with the untouchables wherever our societies have abandoned them.

Then we’ll see why it is a Good Friday.