A common lament of those working in the area of prison policy is a lack of information. This has not been one of those weeks.

Since the beginning of the week, a number of documents with either a full or partial focus on prisons – the Irish Prison Service Annual Report 2019, a draft Programme for Government, and St. Vincent de Paul’s report entitled “The Hidden Cost of Poverty” – have been published. Individually, each sheds some light on current prison policy or future directions. However, read together, using one to interpret and augment the other, they tell a much more compelling and concerning story about the nexus of gender, poverty, and prison in Ireland.

This blog post will briefly discuss each document and propose that prison is the social institution utilised by the Irish State to manage very poor women.

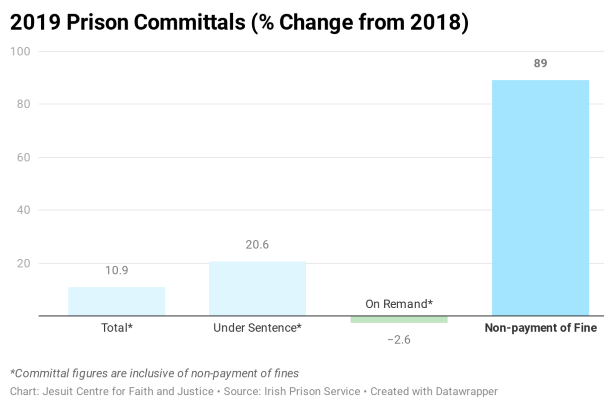

In 2019, according to the Irish Prison Service Annual Report, the number of prison committals increased by over 10% with committals under sentence, following a conviction, growing by over a fifth. A large proportion of this growth can be attributed to a staggering 89% increase in committals for non-payment of fines.

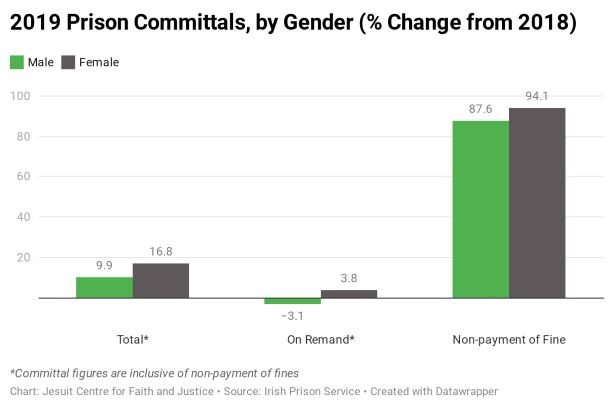

Teasing the committals data apart based on gender, a number of observations become clear. The rate of overall committals is increasing for women, 16.8% last year, compared to men, with 9.9%. With remand sentences, the genders bid adieu at the x-axis as women increase by almost 4%, while men decrease by 3%, even though women are more likely to be arraigned for a nonviolent crime. Notably, women are more likely than men to receive a prison sentence for non-payment of a court-ordered fine, though both are unacceptably high.

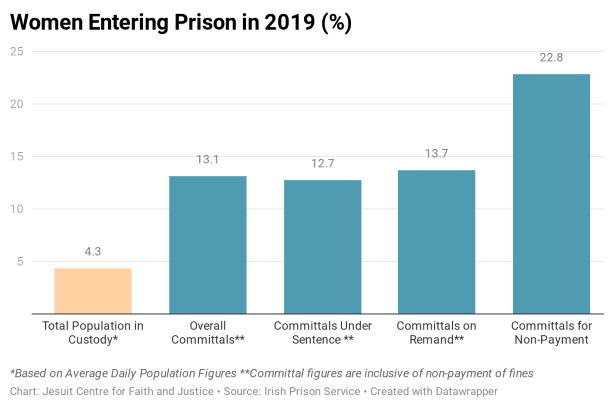

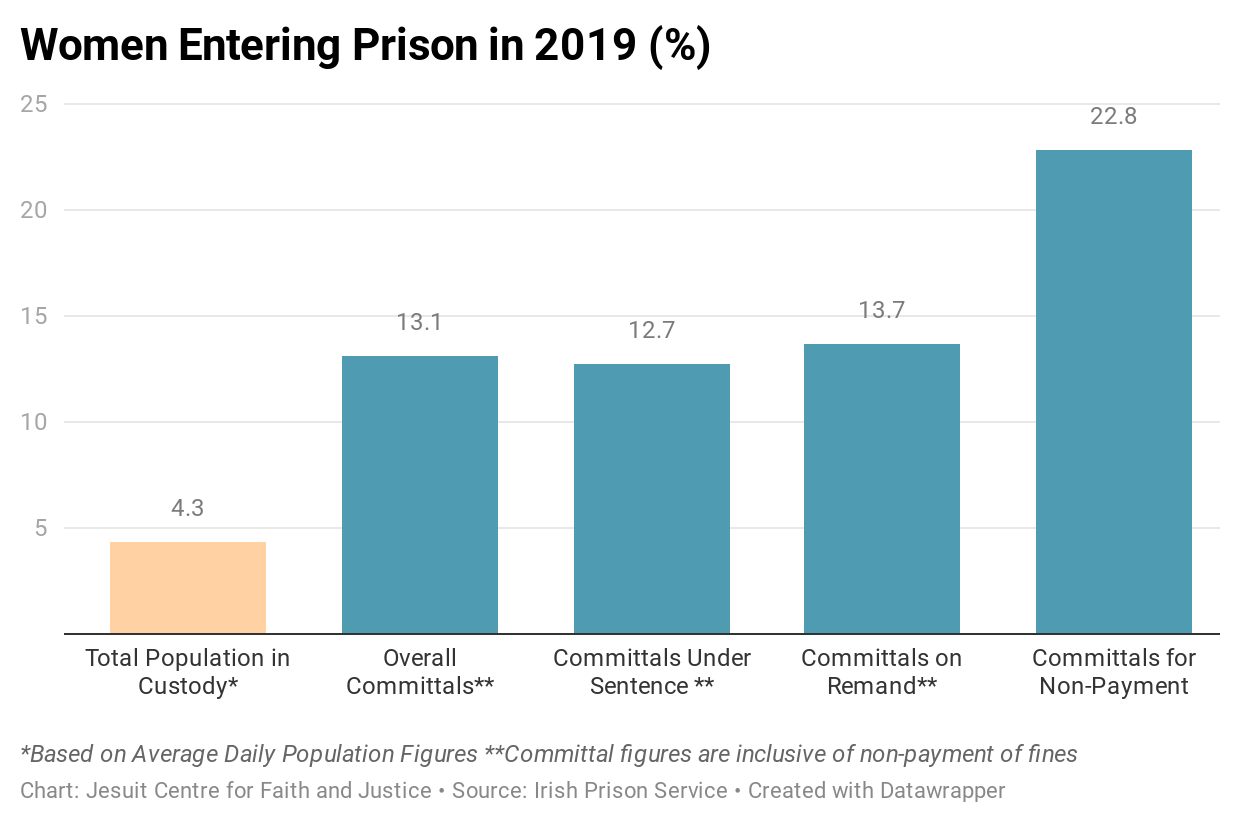

Yet focussing on the increase of female committals still obscures female over-representation within prisons. Women made up 4.3% of the total prison population in 2019 but overall committals, committals under sentence, and committals on remand were 13.1%, 12.7%, and 13.7% respectively. Furthermore, almost one in every four people committed for fine non-payment is female, yet only one in every 25 prisoners is female. This high rate of committal but relatively low population is indicative of a tremendous churn of women entering prison for very short sentences. Often the same women, serving a life sentence in instalments.

Previous prison data suggests that 95% of women incarcerated received sentences for nonviolent petty crimes such as shoplifting or handling stolen goods. Yet with women as primary caregivers or breadwinners, particularly in lower income deciles, such petty crimes are not crimes of wanton excess and salubrious living but often acts of necessity to provide basic essentials for family and dependents.

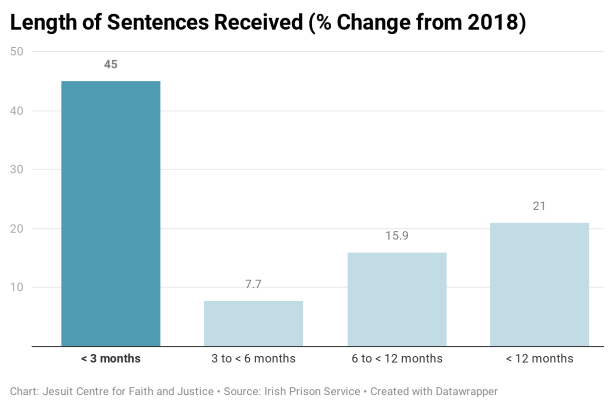

Lastly, coinciding with the doubling of committals for fine non-payment and an increase of committals for women, sentences of less than three months on conviction increased by 45%, compared with much smaller increases for other short sentences. These simultaneous trends suggest that the increased number of women committed to prison under sentence were receiving sentences of less than three months, further supporting a ‘revolving door’ for poor women into prison.

Short custodial sentences are the norm for women. Violence is rarely an aggravating factor. No threat is posed to the immediate or wider community. In 2017, nearly all female prisoners served sentences of less than 12 months, with three-quarters for less than three months. Over-representation for fine non-payment indicates a lack of resources to pay fine and avoid a custodial sentence. We see, emerging from pages of the IPS Annual Report, an archetypal female prisoner.

A poor woman serving a sentence of less than three months for a petty, nonviolent crime.

In the Hidden Cost of Poverty, commissioned by the Society of St Vincent DePaul, an estimated value is placed on the public service cost of poverty in Ireland. This is a key question which is surprisingly absent from discussion within political parties who revere fiscal prudence but permit poverty and deprivation to continue unchecked. While headline figures will be contested and debated – as they should be – the annual cost estimate is €4.5bn with a range between €3bn and €7.2bn per annum.

Singling out the criminal justice system as one of six broad areas of public expenditure, 37.8% of An Garda Síochána’s annual expenditure of €1.76 bn is associated with poverty, totalling €665.3 million. Even more pronounced is the estimated poverty cost of €214.9m for the courts and prison service, equating to 43.2% of their combined annual expenditure of €497 million.

Aside from quantifying the long-term cost of tolerating poverty, a more salient point emerges. In Ireland, a failed system of redistribution is replaced by the criminal justice system to manage those who have been marginalised. A similar analysis is presented by Loïc Wacquant in his book, Prisons of Poverty.

Wacquant observes the growing use of the penal system as the instrument or social institution for managing poverty and social insecurity. The institution and various branches of the welfare state have been usurped by the prison and other surveillance infrastructure to contain the social disorders created by economic deregulation and social-welfare retrenchment.

Lastly, the draft Programme for Government makes a number of pledges, hard-fought for by many campaigners and researchers, on spent convictions and the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture. However, the overall direction on prisons remains unclear. Those over-represented cohorts in our prisons – women, Travellers, the mentally ill, the disabled – do not get a mention. Some issues are easier to solve.

At present, the prevention of Covid-19 spreading to the prison population has been under-girded by a successful policy of temporary release to significantly reduce prison numbers from over 4,200 in March to around 3,700 today. While committing to the availability of modern detention facilities, the draft’s commitment to adequate capacity is woolly in its intention and, in the context of years of prison over-crowding, suggestive of future capacity increases.

There has been nothing to suggest that when the courts return to full capacity, augmented by a burgeoning police force, that the prison numbers will not bounce back to, or surpass, March’s peak. One thing is clear. Any additional capacity or increase in prison population will be over-represented by poor women.

Prisons have to accept people convicted by courts. Responsibility lies here with those who pass sentence. Any assumption among judges that a short prison sentence will put a person back on the straight and narrow needs to be quickly dispelled. The firm hand of a patriarchal and classist society can be traced through the clear gender disparities which exist in sentencing trends, particularly remand and committals for fine non-payment.

Imprisonment is not a solution for poverty; it only further compounds chaotic lives. Imprisonment should not occur because of lack of means. In some cases, it is a matter of life and death.

At the nexus of gender, poverty and prison, the future is uncertain. Yet, prison can be made to recede in the political and social imagination by a government fulfilling its responsibility to provide for people’s needs through redistributive means.