One can only imagine that Minister for Housing, Eoghan Murphy, breathed a sigh of relief. In the midst of a difficult General Election campaign, his Department was able to publish homelessness figures for December, which for the first time in a year, saw a reduction.

The Good News

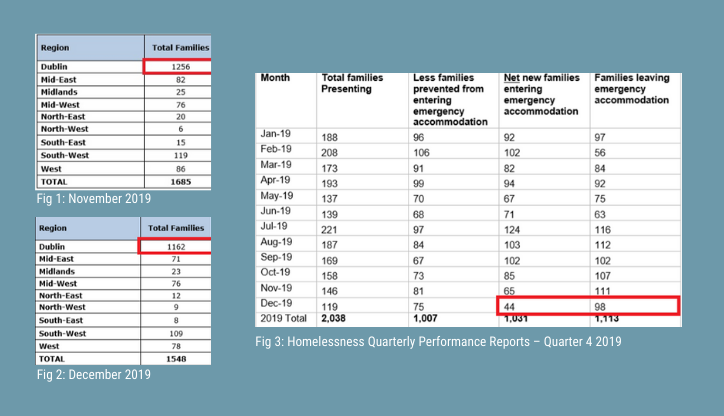

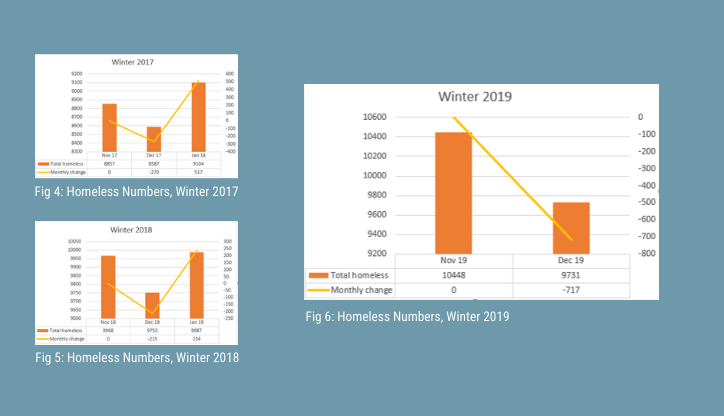

According to the official tally, there were 10,448 people homeless in Ireland in November. It had fallen by 717 to 9,731 in December. Murphy’s reaction was muted, acknowledging that the decrease was “not enough and the number of people in crisis is unacceptably high,” while accepting that this was undeniably a move in the right direction.

The Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice welcomes these numbers. The homelessness scandal has been deepening for so long that we are eager to embrace any and all signs of hope. Yet we have considerable reservations about any attempt to suggest that this is a turning point.

The Bad News

We are not the only ones to have reservations about the good news. Analysts at Inner City Helping Homeless have noted discrepancies in the Departmental report. At one point, the public was told there were 94 fewer families homeless in the Dublin region, but the quarterly report presents this number as only 54.

The group identified serious mistakes in the original calculations, which in one instance suggested that the number of people living in Temporary Emergency Accommodation (situations where people have dwellings without any further support) grew by 2,186 in a single month.

Even without these anomalies, it is important to read the data in context. What we have noticed over the last few years is that the month of December has seen a reduction in the numbers from November, but they then jump again – by a greater amount than they fell by – in January. Based on this pattern, if the decrease is not due to another re-classification of homelessness, we can now expect to see another sizeable increase when the figures for January 2020 are released later this month.

There is no clear answer as to what causes this trend. There is long-standing research on the media representation of homelessness which recognises that press coverage of the issue reaches a peak around Christmas and one explanation might simply be based on compassion; landlords are human too and they don’t want to evict people over the Christmas period. This explanation satisfies Occam’s Razor and helps to explain why the numbers rebound to an even greater degree in January.

The Bigger Picture

Those familiar with the context of homelessness recognise that the official figures published by the Department are deficient, even when compiled scrupulously. The numbers exclude rough sleepers, those in domestic violence shelters, those in Direct Provision who have been granted permission to stay in Ireland but have nowhere to go, and the vast numbers of people couchsurfing or in unsustainable ad-hoc arrangements with family and friends. The numbers are published without a clear schedule. They are often dispatched late on Friday afternoon or over the weekend, meaning that they largely miss the news cycles. As it stands, the late numbers which were published in January are still not on the main website for data.

Our European peers often function with broader and clearer definitions of homelessness. Finland – a country that is similar in many ways to Ireland – is recognised as a global leader in the battle against homelessness. Their definition offers a more straightforward, common-sense understanding of the picture. Arguably, if Ireland adopted such obvious measurements, the sheer scale of the numbers would be politically devastating. If we are (rightfully) distressed by the present figures, how would we cope if we adopted a more transparent definition?

The homelessness crisis has been building for years in Ireland. It would be a foolish optimism to imagine that two or even three months of progress indicate that the solution has been found. Informed by the work of Peter McVerry SJ, the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice does not believe that the current government policy can possibly resolve the issue. Without a large-scale commitment to building social housing fit for the 21st century, we will see these numbers tick up and down without the fundamental failures being remedied. If we let raw market forces determine the price of a house, we should not be surprised when the price is out of reach for many.

The analysis from Inner City Helping Homeless is invaluable because it foregrounds how any conversation about resolving this unparalleled human crisis in our society is scuppered in advance if we do not have meaningful data. In the lifetime of this present Government, the Housing Department unilaterally redefined homelessness, adopting an interpretation that made the figures less stark. Between 600 and 1,600 people were removed from the official homelessness list on the basis that their temporary accommodation had its own door. It is beyond tragic if the Government responds to the profound human suffering of living without a home by definitional loopholes or moving numbers around a spreadsheet. Ultimately, we must remember it is not the data that is the crisis. It is the real human beings that concern us. The data is only valuable when it gives us a glimpse of the full scale of human suffering.

The Future

One concrete step for the new Dáil that would make a significant improvement to our potential policy responses is to remove the responsibility for collecting and collating the figures around homelessness from the Department. Without any consideration of the present crisis and without any knowledge of the legitimate questions that have been raised about the reliability of these figures, it makes sense from a democratic perspective to allow the Government’s independent specialists – the Central Statistics Office – to gather this data. That removes the temptation that less noble politicians might endure to massage the figures. It would make the collection transparent, regular, and open to scholarly scrutiny.

The one thing that every person connected to the homelessness crisis has in common is a desire to end homelessness in Ireland. This is true for the Government and for civil society. It is especially true for those experiencing homelessness. Getting our facts right, reliable, and robust is a real first step towards achieving that aim.