Introduction

If the Dáil we elect at the forthcoming General Election lasts a full term, it will oversee the whole five-year period of Ireland’s commitment under the Kyoto Protocol (2008–2012). It will also cover the period during which the international negotiations to agree new and more challenging commitments to reduce our climate-changing pollution will be conducted.

The story of the Irish public policy response to climate change is one of bad news and good news. The bad news is that our record so far is one of failure. The good news includes the fact that we have been warned in sufficient time to make a difference, the issue is now on the public agenda as never before, and the ideas we need to protect and enhance our quality of life are there, ready and waiting to be implemented. But the window of opportunity is closing: we have no more time to waste.

The science is clear: we have ten years to start bringing down global emissions if we are to stop climate change running out of control. The economics are clear: the Stern report concluded it is up to twenty times cheaper to prevent runaway climate change than it is to try cope with its impacts. All we need is the political will to act. And, in the words of Al Gore, political will is a renewable resource, particularly in an election year.

Polluting Ireland

First, the bad news. Among rich countries, Ireland is the fifth most climate-polluting country per person. If everyone on Earth polluted as profligately as the Irish we would need the resources of three planets to survive. Ireland’s commitment under Kyoto is to limit the growth of our greenhouse gas emissions to 13 per cent above 1990 levels by 2012. Ten years ago, the ESRI predicted that if we continued as we were emissions would rise by 28 per cent by 2010. It was not surprising, therefore, that the National Climate Change Strategy, issued by the Government in 2000, stated that: ‘business-as-usual is not an option’. But ‘business-as-usual’ is precisely what we got. The latest Government figures show that climate pollution has risen by 25 per cent, almost twice Ireland’s Kyoto target, and exactly in line with the ESRI estimate of what would happen if we failed to take action.

Ireland’s response so far to the threat of climate change can be characterised as ‘never missing an opportunity to miss an opportunity’. The Government agreed to the 13 per cent Kyoto target on foot of independent expert advice on how it could be achieved while sustaining our economic development. This 1998 international consultancy report recommended a carbon tax to put a price on pollution, switching Moneypoint Power Station from dirty coal to cleaner gas, phasing out peat-fired power stations, tightening the building regulations to make homes much less wasteful of energy, and linking VRT and motor taxation to the amount of pollution a vehicle produces. So far, none of these policies has been implemented.

What explains this inaction? Quite possibly our political leaders have felt that we, the people, were busy enjoying Ireland’s new-found prosperity and to disturb us with talk of storm clouds on the horizon would not bring political rewards. Better to let sleeping dogs lie. More generally, this is an explanation for the keep-the-good-times-rolling feel of the 2002 General Election. But if the last five years have taught us anything it is that prosperity alone does not solve everything. We know prosperity alone doesn’t solve health care, child care, or elder care. And now we are finding that it doesn’t solve ‘planet care’. Indeed, it makes some things worse. Just think of the impact of longer commutes and increasing gridlock on family and community life. It is no coincidence that the fastest growing source of Ireland’s climate pollution is carbon emissions from road transport, which have risen by 160 per cent since 1990.

Still Time to Act

The good news is that we still have time to rise to the challenge presented by the climate crisis. Like all crises, it is an opportunity as well as a threat.

An economic opportunity: Ireland is rich in the natural resources of the new low-carbon era – wind, wave, tide, and biomass. Even solar energy has significant potential in this country. Investment and R&D will pay dividends for private entrepreneurs and public policy. In addition, cutting energy waste will save money in a time of rising fuel prices and declining oil production.

A social opportunity: Better planning, housing and public transport solutions bring multiple benefits. The consequent reduction in our car dependency, which is among the highest in the world, would not only reduce pollution and improve the quality of life for cash-rich, time-poor commuters, but it would also reduce inequality and promote social inclusion in a society where a quarter of all households do not own a car.

A political opportunity: The political leaders who show the vision to understand and respond to the crisis will be rewarded and remembered – as we remember those who struggled a hundred years ago, whether for female suffrage or national independence; as we remember Whitaker and Lemass for transforming the economic outlook fifty years ago; as we remember those who put aside political and sectoral interests to respond to Ireland’s economic crisis twenty years ago.

Indeed the parallels with 1987 are striking. In 1987, after a decade of profligacy, procrastination and tinkering, Ireland’s national debt stood at 125 per cent of GNP. Today, our climate pollution stands at 125 per cent of 1990 levels, the baseline for international comparisons. In 1987, cross-party consensus and a new model of social partnership were required to take the tough decisions needed to pull Ireland out of that crisis. Those decisions were not without costs – costs which could and should have been spread more fairly. But nobody now doubts the benefits of the transformation those policies brought about. Indeed, everyone now claims a share of the credit for the resulting prosperity. And our national debt today stands at just 28 per cent of GNP.

But now our reckless pollution is incurring a new national debt. Buying pollution permits overseas, which is the Government’s principal response to Kyoto, is a form of foreign borrowing. It merely puts off the day when we have to reduce our pollution at home. As China, India and the rest of the developing world grow their economies in order to lift their people out of poverty they will pollute more, until they are using their fair share of the atmosphere’s absorptive capacity. Then they will have no spare permits to sell to us and by then we must not be polluting any more than our fair share. Our politicians know this. Indeed, they have put a figure on it: at the EU Summit in March 2007 they agreed that Europe and other rich developed countries will have to cut climate pollution by 60 to 80 per cent by 2050.

The Sooner the Better

The kind of transformation required cannot happen overnight, and it certainly cannot be achieved at the last minute. There are no quick-fixes or short-cuts to climate security. The notion that technology alone can ‘fix’ climate change is not realistic. There is a need to move from the anthropocentric idea that human beings are the centre of the universe and the subduers of the earth, to an ideology that values and cherishes the environment. Climate is the latest facet of nature to show vulnerability to human action. Now, confronted by what Sir David King has labelled ‘the biggest challenge our civilisation has ever had to face up to’, it is clear that only a reorientation of how we view nature offers a viable solution to the problem of global climate change.

Just as in the case of the treatment for many diseases, the sooner we do something about climate change, the easier it will be and the greater our chances of success. The longer we leave it the more traumatic it will be and the more difficult it will be to stop climate change running out of control. The climate crisis and oil peak mean change is coming whether we welcome it or not. Our choice is what kind of change and whether we manage it ourselves by making the shift to sustainability in a planned step-by-step way, starting now, or whether we wait and let change happen to us by way of shocks, disruption and upheaval down the line.

We know that long-term targets present difficulties for politicians. This is one of the reasons Ireland is failing to meet its Kyoto commitment. The Kyoto target was agreed in 1997 but only falls due in 2008–2012. That was too far over the horizon, given that political life is dominated by the twenty-four hour news cycle and the five-year electoral cycle. When Ireland signed the Kyoto agreement in 1997, the political parties which made up the Government of that time hardly expected to be still in power in 2007, never mind to be strong contenders for a return to office and therefore in charge for the full period covered by Kyoto. The new targets set by the EU are for 2050 but the tough decisions need to be made now.

An Annual Carbon Budget

If we are to have any hope of success, we need to shorten the gap between action – or inaction – and accountability. Organisations such as Friends of the Earth are now proposing a Climate Protection Act which would provide for 3 per cent year-on-year reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Enshrining the long-term targets in law, and requiring that an annual ‘carbon budget’ be presented to the Dáil alongside the existing fiscal budget, would mean that the struggle against climate change would become part of the mainstream of the political system. Any pollution overshoot would be expected to evoke immediate corrective measures – just as it can be expected that signs of inflation will give rise to a change in interest rates and rising public debt result in adjustments to public spending.

This approach is already emerging as international best practice. California has enshrined in law an 80 per cent reduction by 2050, with an interim target for 2020. Three bills to provide for similar legislation are now being proposed in the US Senate, including one that is co-sponsored by John McCain and Barack Obama, leading Republican and Democratic contenders for the Presidency. Now, the UK Government has published a bill with five-year targets and carbon budgets, while the Conservative and Liberal Democrat opposition parties support annual targets.

Conclusion

Today, climate and energy cast a shadow over public life in Ireland in the same way that unemployment and emigration did twenty years ago. We need a similar sea-change now to the one we engineered at that time. Then, the ‘Tallaght Strategy’ and social partnership provided a framework for national recovery. Today, a climate law can provide the framework for pollution reduction. It will give an impetus for private enterprise and public policy innovation to respond to the challenges and grasp the opportunities on the pathway to a low-carbon future. And everyone will able to claim a share of the credit for the resulting sustainability.

Notes

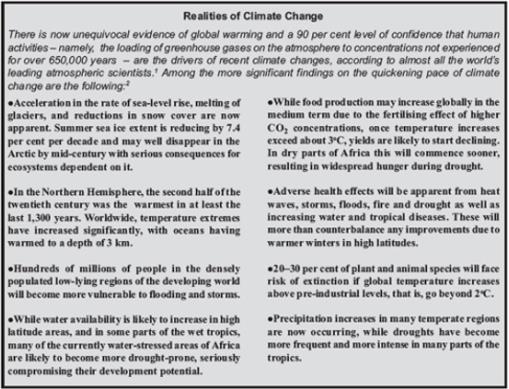

1. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2. These facts are extrapolated from the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, which synthesised research output from across the peer reviewed literature over the past seven years. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.)